The Event Horizon Telescope, a global network of radio telescopes that aims to capture images of the supermassive black hole at the center of the galaxy, collected a petabyte of data every night of observation in 2017. That’s one thousand trillion or one million billion bytes of data.

For perspective, the Library of Congress has archived more than 300 trillion bytes of data. The telescope collected more than three times that amount of data per night of observation, which was four nights in 2017.

However, the collection of such larges amounts of data results in a problem for researchers.

Right now, it’s more efficient to use airplanes to fly the hard drives storing that data in crates around the world for research purposes than it is to send it electronically.

And to access that massive amount of data, researchers must travel to a site housing those hard drives.

In 2018, the amount of data the network collects will almost double.

This is just one logistical hurdle a University of Arizona-led international team hopes to circumvent in the next five years using a $6 million grant awarded by the National Science Foundation’s Partnerships for International Research and Education program, known as PIRE. An additional $3 million was added to the pot by international collaborators and their respective agencies, raising funding to a total of $9 million.

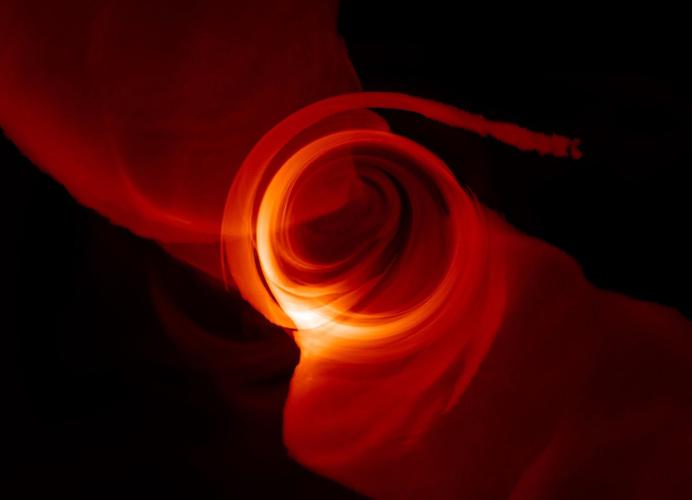

Studying the black hole in the turbulent center of the galaxy will test Einstein’s theory of general relativity under extreme conditions.

The UA plays a leading role in the telescope, and now the UA-led PIRE grant will allow the team to develop the tools and infrastructure needed to make the telescope network more efficient and useful for years to come, said Dimitrios Psaltis, the project’s principal investigator and a UA astronomy professor.

“We have used existing technology and tools in order to make (the telescope network) work, but in order to take it to the next level, we have to up our game,” he said.

Without PIRE, the telescope work could go on, but it’s like a dishwasher, Psaltis said.

“It’s not necessary, but if you have a dishwasher, then you don’t have to do it by hand, and you use your time more efficiently.” He said he expects the telescope will produce more science than originally planned because of the PIRE funding.

One expected outcome is using that funding to develop the algorithms and tools necessary for the telescope team to share and store data using CyVerse, another UA-led endeavor providing the cyberinfrastructure to handle large scientific datasets, cutting delivery airplanes out of the equation.

A few other challenges unique to the telescope include very large computational demands, coordinating over 200 people from 50 institutions on five continents and determining the best two-week window of time with clear weather for 10 telescopes around the world to simultaneously observe.

The project is also expected to spin off technologies that go beyond its primary goal and could have applications in other areas of science, ranging from self-driving cars to renewable energy production to national defense. Spinoff technology and techniques will be made available for any other project that needs them.

For example, last year when the Large Interferometer Gravitational Wave Observatory detected gravitational waves from the collision of neutron stars, researchers emailed astronomers around the globe to turn their telescopes and find the corresponding light source.

Soon, the observatory is expected to detect about 10 gravitational waves per year, and this method of searching is ineffective.

The tools and techniques developed by the telescope’s PIRE project should help address issues such as these, Psaltis said.

Besides research goals, PIRE also requires an educational goal and international partnerships.

Through streamlining communication and data-sharing, Psaltis hopes to engage graduate students around the world and give them experience that they otherwise wouldn’t have access to.

Collaborators on the PIRE program are from the University of Illinois, the National Center for Supercomputing Applications, Harvard University and the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory.

Internationally, the team includes researchers from Germany, Mexico and Taiwan.

UA collaborators also include PIRE co-investigators and astronomy professors Feryal Ozel and Dan Marrone.