The Dunbar School was Tucson’s only segregated school for more than 30 years. Desegregated in 1951 with a name change, it closed for good in 1978 and has stood largely unoccupied for decades.

To help mark its centennial and plan for its future, Debi Chess Mabie will spend the next two years working as part of a coalition that hopes to turn the forgotten campus into a thriving community hub that preserves and celebrates the city’s black history.

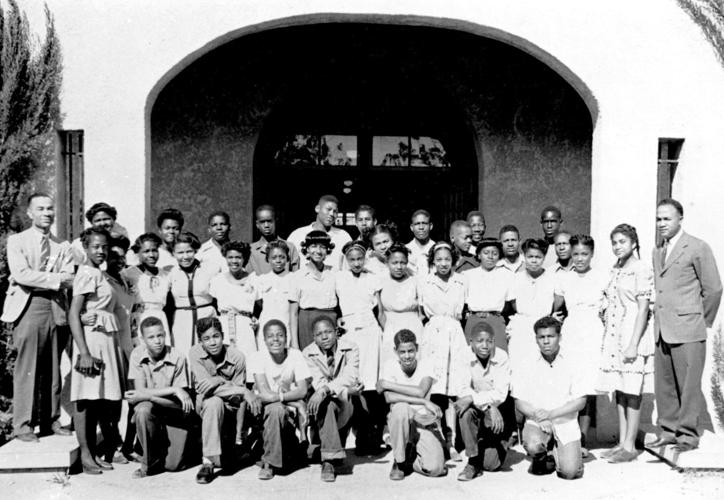

Dunbar School in the 1940s.

Mabie was appointed by the University of Arizona’s College of Social and Behavioral Sciences as its first community impact fellow and will team up with the Dunbar Coalition, which oversees the property, in this preservation effort, which may include space for a new museum, community gatherings, businesses and nonprofits.

“This really is about taking something as a symbol of who we were as a county at a particular moment in time, and making it into a space that will become a symbol of who we want to be,” Mabie said.

The school, 325 W. Second St., is tucked away in the Dunbar Spring neighborhood between Barrio Anita and the West University neighborhood. The original school’s large windows flood the hallways with light as dusty classrooms sit empty except for a few old desks and an age-worn piano.

There is much work to do in the buildings that housed John Spring Junior High and Dunbar Elementary Schools. The buildings closed in 1978. Just a few rooms are used today

The addition next door, built in the 1950s, is mostly vacant now except for a few hubs of activity: the Barbea Williams Performing Company in a single room on the first floor and the Dunbar Barber Academy in a corner of the second floor. The auditorium is also rented out for quinceaneras, weddings and weekly slide-dance classes.

Together the two buildings are known as the Dunbar Pavilion, and only a small section of the combined 60,000 square feet is regularly occupied. Less than half of the property has been repaired.

“It’s a beautiful space, you can just feel the souls of the people who were here,” Mabie said as she walked through the hallways.

And while those souls are important reminders of the school’s valuable history, they also mirror what some say is the black experience in Tucson.

“It’s kind of like black folks never existed in Tucson. Our history is still not talked about,” said Barbara Lewis, who attended Dunbar from 1942 to 1951. She is also vice president of the Dunbar Coalition, the governing body of the Dunbar Pavilion, comprised of school alumni, the Tucson Urban League, the Juneteenth Festival committee and the Dunbar Spring Neighborhood Association.

Dunbar Junior High School’s class of 1946.

Segregated school until 1951

The school is named after renowned African-American poet Paul Laurence Dunbar and served Tucson’s black students from 1918 until the state ordered desegregation in 1951. The addition was built and the school then became John Spring Junior High School. It closed in 1978.

The Tucson Unified School District sold the buildings to the coalition for $25 in 1995. Since then, volunteers have been working to keep it alive. They realized that if they didn’t have a full-time paid employee, the place would just keep hobbling along, Mabie said.

Mabie, a Chicago-transplant seven years settled here, was executive director of the Arts Foundation for Tucson and Southern Arizona before taking on the Dunbar project. She has a master’s degree from the University of Illinois at Chicago in urban planning and policy.

She saw the centennial and national discussion on race as a sign to reflect on what Dunbar provides for the community. She decided it was time to act and with the help of the UA, her new role to work with the Dunbar Coalition was created.

“Their mission was in perfect alignment” with what she wanted to achieve, Mabie said about the coalition.

“We are committed to communities, and our college in particular is interested in social issues and looking at racial dynamics and racism in the U.S.,” said Monica Casper, the college’s associate dean for faculty affairs and inclusion.

The college decided to split Mabie’s salary for the two years with the coalition, and appoint her as the college’s first community impact fellow. She is the only paid member of the coalition.

But the “UA is not taking over Dunbar,” Casper said. “There will not be a big ‘A’ on it.”

Mabie “wants to help keep a black legacy and that’s what we want,” Lewis said, speaking on behalf of the coalition. “It’s been hard to be black in Tucson, to hold on to heritage and legacy here. This is the last vestiges. We have no intent on losing it.”

The west entrance of the old Dunbar school. An estimated $1.5 million is needed to renovate the 60,000 square feet of space in the school.

Big plans for

old school

Through breathing life back into the empty spaces and attracting interest, Mabie seeks to not only anchor the black community, but also to reverse the effects of segregation.

“Chicago is a city of neighborhoods. Tucson is very different that way.” There’s no demarcation, other than Dunbar, of the black community in Tucson, Mabie said.

“Of course, there’s importance in convening with people who are like you and share your values and heritage and history, but we also want to make sure we share that outside of African-American communities and that there’s a reciprocal relationship of cultures.”

She envisions all the spaces regularly occupied by organizations that align with the coalition’s vision to provide access to education; health and well-being; civic engagement; economic development and entrepreneurship; and arts and culture, she said.

“We know that there’s a need to occupy the space,” she said. She’s currently speaking with a potential tenant, although she did not feel comfortable naming them before a deal was reached.

The revenue generated through rent will then be put back into renovating more space. To get the building to where it is now, the late Cressworth Lander worked with U.S. Rep. Raúl Grijalva to secure more than $800,000 of Pima County bond election funds to do most of the renovations. But “that money just kind of dried up,” Mabie said.

“We need to raise an additional $1.5 million to complete the project on both sides,” Mabie said. This will come from a combination of grant writing, philanthropy and revenue from tenants.

Part of the plan also includes a representation of African-American history through some kind of exhibit, whether it’s a traditional museum, a display or through programming.

The Dunbar Coalition boardroom is home to exhibits on the role of African-Americans in Tucson.

“This isn’t just about black culture and black history,” she said, adding that it is about missing pieces of Tucson’s history and identity.

She wants to give voice to the unique experience and history of blacks in Tucson — a lofty goal to reach in two years.

Mabie said it’s not enough time, “But it’s a really good start, and I think it’s a great motivation for all of us — the folks that are allies and this coalition that has been doing this work for so long — to get a move on.

“If this can become what it needs to become, then it’s an example of the best of what Tucson is about,” she said.