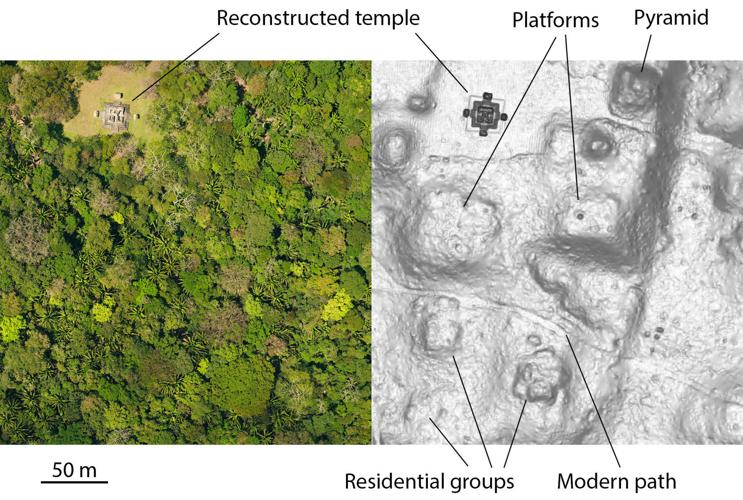

Most of the ancient Maya archaeological site of El Ceibal, in north-central Guatemala, is buried in dense jungle. Eroded stone ruins create vague mounds and outlines on the crowded jungle floor.

Harvard archaeologists excavated and mapped in detail almost 2 square kilometers, about 500 acres in size, of the site and surveyed another 6 square kilometers, about 1,500 acres, in the 1960s. For decades following, the site was left alone.

“Forty years is a long enough time that you get new questions and new ideas,” said Takeshi Inomata, University of Arizona professor of anthropology and Agnese Nelms Haury Chair in Environment and Social Justice.

Armed with new cultural interpretations, Inomata and his international team of archaeologists — from the United States, Guatemala and Japan — returned to the site in the early 2000s and during the dry seasons of the next 13 years to continue to excavate a piece of the area surveyed by Harvard.

“The jungle is always the big barrier” Inomata said. The team dug a square kilometer, but even that took a long time.

So they commissioned the use of high-tech tools, such as an airborne laser detection system called LiDAR, for light detection and ranging, to map an unprecedented 470-square kilometers — roughly the same size as the city of Scottsdale — of the site over the span of a few days in 2016.

“By that time, LiDAR was pretty well-proven research method,” he said. “It helped us look at a wide area that was basically unthinkable before.”

The team extrapolated what it learned from the excavations to interpret the surface features which LiDAR mapped in 3-D.

Their work revealed the shape, size and location of more than 150,000 ancient Maya architectural remains including pyramids, platforms, ceremonial centers, roads, water reservoirs and more.

Earlier digs revealed fewer than 1,000.

“We don’t have standing buildings,” Inomata said. “The remains of collapsed or partially eroded buildings, that’s what you can see in LiDAR.”

Architecture can be used to understand population movement and culture because, “In different periods you see different kinds of structures,” said Inomata. Tracing how those structures spread and evolve over time give insight into the dynamic history of Maya civilization.

The LiDAR survey was conducted by the University of Houston’s National Center for Airborne Laser Mapping. Following the LiDAR analysis, the team dug into much smaller sites of interest to learn more.

Inomata’s team made some unexpected discoveries.

It is generally thought that the process of settlement in a certain area by different peoples happens gradually. First comes agriculture then, after further development, comes ceremonial complexes.

What they found was that elaborate ceremonial complexes were built almost at the same time the Maya settled and began farming about 3,000 years ago. The early appearance of these ceremonial complexes “was important driver of society, and this includes the economy and lifestyle” of the Maya, Inomata said.

“We see the emergence of Maya civilization as a really drastic change, not gradual, and we see subsequent population growth in a spatial scale that was unthinkable before LiDAR,” he said.

They also found that “the maps that Harvard made were incredibly accurate considering they were all ground survey,” said Melissa Burham, paper co-author and UA graduate student in anthropology, in a statement. “But with LiDAR we found a lot more buildings than were on the map previously.”

Inomata’s research was funded by the Alphawood Foundation and the LiDAR commission was paid for by the Japanese government.

Next, Inomata wants to study a site that was home to the Olmecs in Tabasco, Mexico. The site is down river from Ceibal, and the river is a potential communication route between the two civilizations.

In Tabasco, Inomata hopes to use LiDAR to scan an even larger area and hopes that more archaeologists adopt a similar method of archaeology.