It’s been more than 30 years since Steve Clifford, a senior staff scientist at the Tucson-based Planetary Science Institute, published a paper in which he predicted that lakes of stable liquid water could be found underneath the polar ice caps of Mars.

In 1987 Clifford was fresh out of his doctoral program from the University of Massachusetts and working at the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston. His prediction might have finally found validation more than three decades later.

On July 25, researchers in Italy announced that they might have found just what Clifford predicted.

“It’s always nice when someone proves that your theoretical work has some relationship with reality,” said Clifford. “There wasn’t an opportunity until radar sounders arrived on Mars in the mid-2000s. That opened the door to subsurface investigation.”

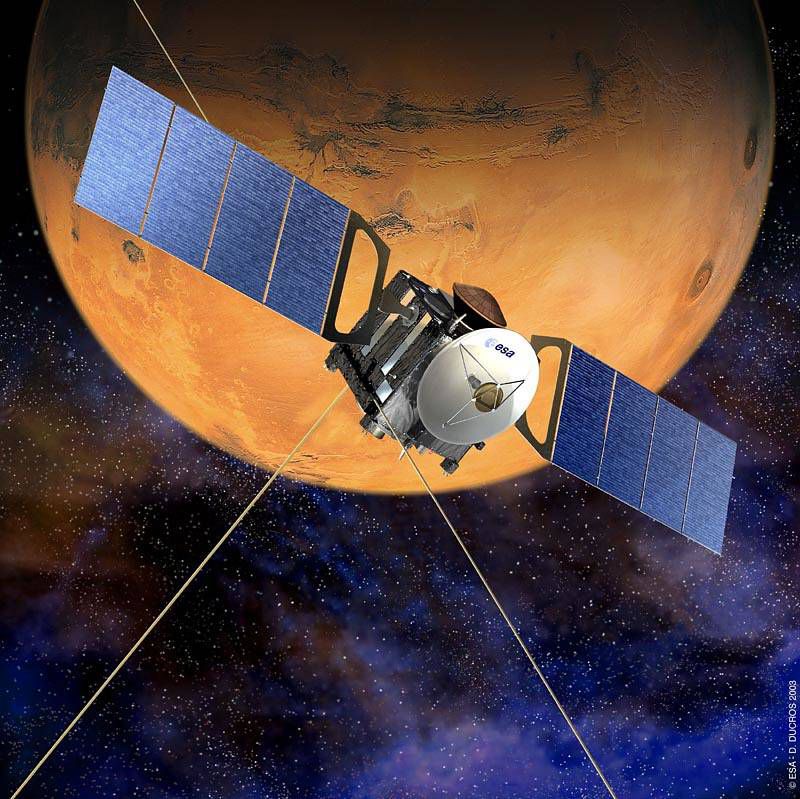

The team used MARSIS, a subsurface radar sounder aboard the European Space Agency’s Mars Express Orbiter, to locate the potential body of liquid water.

Shortly after MARSIS arrived in orbit, it unfurled a 130-foot-long antenna in two pieces. Together, the pieces are the same length as the tallest building on the University of Arizona campus, the Gould-Simpson Building.

The giant antenna bounces radar off geologic features as deep as 2.5 miles below the Martian surface to reveal underground secrets that go unseen by cameras in orbit.

MARSIS researchers believe the lake is about 1 mile beneath the ice and 12 miles wide. They do not know how deep it is, but estimate that it is at least 1 meter thick.

Through support from NASA, Clifford was a funded member of the MARSIS team from arrival in 2005 until 2010.

Lakes form under ice sheets on Earth. Clifford thought, might this also happen on Mars?

Water might exist under sheets of ice on Mars for three reasons. Radioactive elements release heat when they decay. The ice acts like a blanket, trapping any such heat. And salts present in the Martian dust lower the temperature at which ice melts.

As MARSIS orbits Mars, it scans the subsurface, looking for highly reflective areas that might be water.

“There are lots of things that can give you reflections,” Clifford said. “You want to make sure you’ve looked at competing explanations.

“It’s not conclusive, but it’s highly persuasive,” Clifford said.

Excitement stems from the fact that where there’s water, there might be life.

If water is found there, it would likely have melted from ice that is much older than the ice sheets above, which are tens of millions of years old, said Shane Byrne, assistant department head of the University of Arizona Lunar and Planetary Laboratory. “It could contain material from past periods in Mars’ climate, but we don’t know the exact data of the melting event.”

Others are skeptical, Byrne said, because this single location doesn’t seem to be anything special. He doesn’t see reasons why that particular area would be warmer than others, and there doesn’t seem to be any surface features hinting at what lies below.

“It could also be a brine layer,” said Lynn Carter, an associate professor at the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory with expertise in radar remote sensing. She also pointed out that there are other reflective areas nearby. “What is the interpretation of those other areas?” she asked.

“This is the one spot where they had the strongest data — where they collected the most overlapping radar measurements,” Clifford explained.

All agree that the next step is to follow up with other radar.

SHARAD, a shallow radar detector also aboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, cannot see as deep underground as MARSIS, Carter said, but there are ways to improve its performance.

Future instruments are coming up the pipeline that might have the ability to probe as deep.

Ultimately, follow-up with other instruments, continuing the analysis of the MARSIS data and collaborating with other teams that have collected their own data will help bolster this most recent hint of water on Mars.

Until then, the hunt for water continues.