If liquid water hides beneath the mile-thick slab of Mars’ southern polar ice cap, then it could be due to recent underground volcanic activity, according to a new study by two University of Arizona researchers in the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory.

A group of Italian planetary scientists announced in January 2018 that it had detected water under a portion of the icecap using radar from Mars Express, the orbiting European Space Agency satellite.

The study, however, did not explore why the water is able to persist at that location, except by assuming salt would have to be present to induce melting.

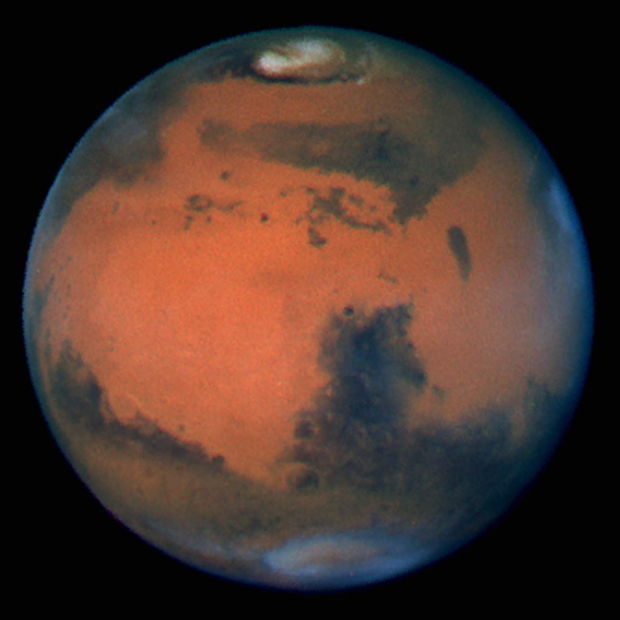

Nevertheless, this was big news: It’s the largest body of liquid water ever claimed to exist on the red planet. Other studies have suggested water is locked up in Martian rocks or possibly exists in damp, transient streaks along crater slopes.

Michael Sori, UA associate staff scientist, and research associate Ali Bramson modeled the conditions necessary to produce liquid water in that location.

“We don’t want to say whether the (Italians’) radar interpretation was wrong or right,” Bramson said, “but if it is right, what are the geological conditions needed to get melting there?”

The two-person team published its findings in the American Geophysical Union journal Geophysical Research Letters last week.

“Salt can lower the melting temperature of ice and make it easier to melt. That’s why we salt the roads in other parts of the county,” Sori said.

But “the conclusion of our model was that even with added salts, it would just be too cool without subsurface magma,” he said. “If there’s magmatic activity in the local region, it can raise the heat flow enough in this specific spot. That would be nice because it can explain why the liquid was in one spot under the cap.”

Sori and Bramson estimate the magma would have had to have been active about 300,000 years ago — which is recent in geologic timescales.

“There is a time lag needed for the heat to diffuse through the crust,” Bramson said. “It’s like defrosting a turkey: You put it in the oven, and the center won’t instantly be 200 degrees.”

Volcanic activity within the last 300,000 or so years is much more recent than others have suggested, but that is expected to just be another point to address as the debate continues.

Sori and Bramson also took into consideration other variables that might contribute to the melting, such as dust, pressure and more, but these considerations don’t have as large of an effect on reducing the melting point, Sori said.

The media portrayed the 2018 discovery as a sub-glacial lake, but Bramson suspects in reality, it would be more like a Martian slushy — liquid mixed with ice, dust and salt.

Sori and Bramson said they aren’t taking a side on the debate as to whether the water is real or not, but they do hope this contributes to the larger discussion of water on Mars and offers more ways to test the Italians’ hypothesis.