DOUGLAS — Like many one-horse towns after the one horse leaves, this former smelter town has struggled since it lost its largest employer almost 30 years ago.

Residents hope art — and artists — could help give Douglas new life.

One pair of artists scoured the nation and chose Douglas. Another opened a coffee shop and is promoting cross-border art shows. Yet another is creating a museum full of art cars.

There’s something magical about Douglas, artist and coffee shop owner Robert Uribe said. “We just need to enhance it.”

A Church for $28,000

The landscape, slower pace of living and cheap real estate brought two San Francisco area painters to Douglas.

“We had been in the Bay Area, each of us for a considerable length of time, sort of fed up with congestion, high prices,” said David Ivan Clark, a Canada native.

He and his partner, Mieko Hara, a Japanese painter, looked at more than 30 schools, warehouses and old churches across the country. In the end they bought a white church near the border for $28,000 — about a year’s worth of rent in Oakland — in a town they knew nothing about.

Although Douglas is the second-largest city in Cochise County, behind Sierra Vista, these days the town is not gaining many new residents. Since 1990, its population has gone from about 13,000 to 17,000, a much lower growth rate than the county and the state.

That lack of demand for property presents an opportunity to artists looking for work space and to potential business owners looking for a cheap place to set up shop.

Uribe and his wife, Douglas native Jenea Sanchez, moved back in 2011 and soon after got a small business loan to open a coffee shop downtown, right on G Avenue, the city’s main drag. In 2014, they bought the building.

“Douglas is not a disposable income town,” he said. “Our business does OK, but we serve a bigger purpose.”

That purpose is building relationships on both sides of the border. Since the cafe opened, Uribe and Sanchez have hosted photography and art workshops, open mic nights and, earlier this month, a financial aid night.

This summer, the young couple, both artists, started an art walk and in October they held their first binational event, which coincided with the largest binational art installation on the border put on by an indigenous artist collective.

In those two days, Galiano’s Café & Smoothies took in nearly as much as it normally makes in a month, Uribe said.

“There are a lot of things we can talk about that need improvements,” said Uribe, who plans to run for mayor. “But it all starts with a positive attitude.”

Mining fortunes

In its prime, Douglas was a boomtown.

“Every store downtown was occupied,” said Eddie Page, 83, whose grandmother moved from Agua Prieta in 1910. His father, coming from Oklahoma, decided to stay in town after his car broke down on their way to pick oranges in California.

“There must have been 12 bars, four banks, more money in this town than you can ever imagine,” he said.

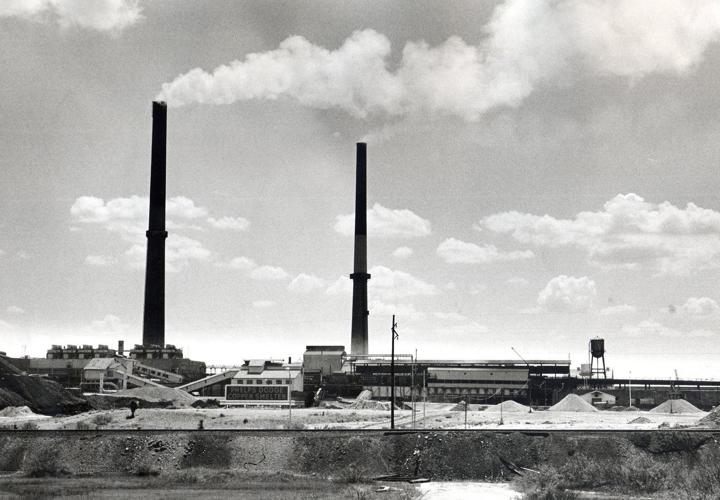

Located in the Sulphur Springs Valley, Douglas was founded in 1901 by the Phelps Dodge company to accommodate its nearby smelter. By 1914, the town had about 5,000 residents and by 1960 it has surged to nearly 12,000, said William Ascarza, a historian, archivist and author who publishes a weekly column in the Arizona Daily Star.

The company had stores and would build schools, libraries, churches and hospitals in the towns where it operated.

“When we were growing up, we had pool halls, fine dining,” said Page. “It was fantastic.”

Then, in 1985, federal health officials recorded a blood-lead level of 25 micrograms per deciliter in children in Douglas, about five times higher than the reference level at which the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends public health actions be initiated.

Rather than upgrade the facility to meet federal air pollution standards, the smelter was shut down in 1987, Ascarza said. The stacks were taken down four years later.

Difficult outlook

Now, “the first things you see when you come into town is the prison and a vacant Kmart,” longtime resident Page said.

Douglas has no major private industry, with most jobs in government or retail. The Arizona State Prison Complex is the town’s largest employer, followed by a call center that opened in 2008.

More than 700 Border Patrol agents work in the area, plus custom officers and other federal agents, but most live outside of Douglas.

The once-bustling downtown, located approximately 115 miles southeast of Tucson, is full of plywood-covered windows, buildings with uninhabitable second stories and desolate streets. Recent fires have destroyed several historical buildings.

There have been some economic positives lately, including construction work around a medical complex and a Tractor Supply store. But anyone taking on the city’s challenges has their work cut out for them.

The city faces low education levels, the absence of a full-service hospital, poorly rated K-12 schools, lack of transportation infrastructure, and perceptions of border areas being unsafe, said Robert Carreira, director of the Center for Economic Research at Cochise College.

Even when local shop owners say they love the town, some say it’s hard to feel that love in return.

Marlin’s Saddle Shop, which stands next to an empty building on G Avenue that used to house Chase bank, stays in business because it’s a specialty store not competing with a national chain, said owner Gerry Bohmfalk.

But even that’s not enough. Born and raised in Douglas, Bohmfalk is selling his store. He’s 65 and ready to retire and move closer to his family in Texas, he said.

Ana Altamirano, owner of Son Paises on East 10th Street, grew up between Agua Prieta and Douglas. She thought the success she found selling women’s clothing online would translate to a storefront, but so far the ups and downs have been tough.

“There are times when you have a good week and then you have this kind of slow week, where your stomach starts to hurt because you need to pay your light bill, you need to pay your rent, you need to pay your phone,” she said.

Like many store owners downtown, she said a lot of Douglas residents simply don’t shop in town. Altamirano said she only has herself to blame, or at least the person she used to be.

“I used to do the same thing before I had my own business. I would get my kids and, ‘let’s go to Sierra Vista, let’s go to Tucson,’” she said. “It was a day to go out, it was a day to go have lunch in a nice place, shop at the mall, be around people.”

She said she is determined to succeed and will do her part to keep things going.

“I don’t want my little town to disappear,” she said. “I want to live here for the rest of my life.”

Available opportunities

Although the strong dollar has cut into the purchasing power of Mexican shoppers this year, a growing Mexican economy is still good for Douglas, which depends on its neighbors to the south for more than 70 percent of all sales tax revenue.

The mayor of Douglas, Danny Ortega Jr., along with private business owners and Congresswoman Martha McSally, are pushing for a new commercial port of entry.

The current port in the downtown area, built in 1933 and expanded in 1993, has limited capacity to grow any further. There are plans for a commercial port a few miles west but the proposal has stalled in Washington.

Ortega is looking beyond just the port expansion, which the town projects could bring more traffic through the area and subsequently jobs in things like warehousing or maybe even a truck stop. More than 1,500 head of cattle cross through Douglas every day, he said, which represents millions of dollars passing the city by.

“Maybe we can put a feed lot here, maybe a processing center for beef,” Ortega said. “Can we somehow market or capitalize on that?”

Two local maquiladoras, Takata Seat Belts and Velcro USA, are also looking to expand, he said, which may add up to 60 jobs.

Douglas also has Cochise College, one of the first in the state to offer a pilot training program, which continues to grow. Favorable weather and visibility in the area allows for year-round training.

And the city has a 75-acre Cochise Industrial Park with land available and utilities accessible upon request, along with inexpensive and developable land, the 2013 Arizona border communities road map shows.

The outdoors around Douglas could also become a selling point, said Tom Allen, owner of Good Way Cafe on East 19th Street.

“It’s great for hunting, fishing, hiking, bird-watching,” he said.

Allen moved back to Douglas recently after living in more than half a dozen places while working for UPS. After he retired, he said, he was looking to start a business at a cost that was not prohibitive, and his two daughters live in Douglas.

He sees opportunity to renovate some historical buildings as condos or businesses, as other cities have done. Maybe Douglas could even offer incentives for federal agents to move in, he said.

He’s looking to buy a building downtown, which he calls the heart and soul of a town.

“I was here in 1977 when Phelps Dodge was here and saw the prosperity back then,” he said. “That doesn’t mean it can’t happen again.”

A good town

When Clark and Hara, the Bay Area artists, told friends they were moving to Douglas, some were concerned. They received links to websites that painted a picture of a town where cars smoldered on the edge of the road, riddled with bullet holes.

“There was information out there that if you didn’t look at carefully, you might get an opinion that it’s bad,” Clark said.

But he did more research and found that border cities typically have fairly low crime rates.

When they first moved in the summer 2011 and were working to make the church hospitable, Clark left his bag with laptop, camera and other valuables on the steps. He went back to look for them, but they were gone.

While he waited for the police to file a report, “a lady comes across the corner with my bag on her shoulder. She had been circling the block to return them to me. That would have never happened in East Oakland.”

Attracting artists and getting community events going would be good ways to bring in visitors willing to spend money, said Nubia Romo, owner of Once Upon a Dream, a dance studio inside the Gadsden Hotel.

“Downtown Bisbee, all their businesses are thriving because of the visitors, not because of the Bisbee people,” she said. “If we got visitors to shop here, maybe our community would also start shopping in our town.”

The key to Douglas’ revitalization is to bring in people who don’t depend on the local economy, said Bruce Endres, an architect originally from Minnesota who moved to Douglas in 2005.

Endres, who will run for mayor next year, said other one-company towns like Cleveland and Pittsburgh have managed to reinvent themselves.

“We need to do something different than what they’ve been trying to do,” he said.

For Endres, attracting artists like Clark and Hara is a good start, and so is the presence of Harrod Blank, a California artist and filmmaker who is trying to get the Art Car World museum up and running. (See accompanying story in today’s Tucson & Region section.)

Since 2005, Blank has bought two buildings downtown and has 23 art cars — vehicles transformed into rolling pieces of art — ready for display once the museum is finished.

“I couldn’t do this in Oakland or Berkeley. I couldn’t even do this in Tucson,” Blank said. “That’s what Douglas has. It just needs some money and some love and you can make something happen.”