The CatSat has called home.

A tiny satellite built in Tucson by University of Arizona students and a UA tech startup was blasted into orbit July 3, but at first it was feared lost in space.

But after nearly two weeks, the scientific team at the UA and FreeFall Aerospace finally made contact with the CatSat and is now preparing the nanosatellite for its missions — to test a new inflatable satellite antenna designed at the UA and probe how radio communication works in the ionosphere.

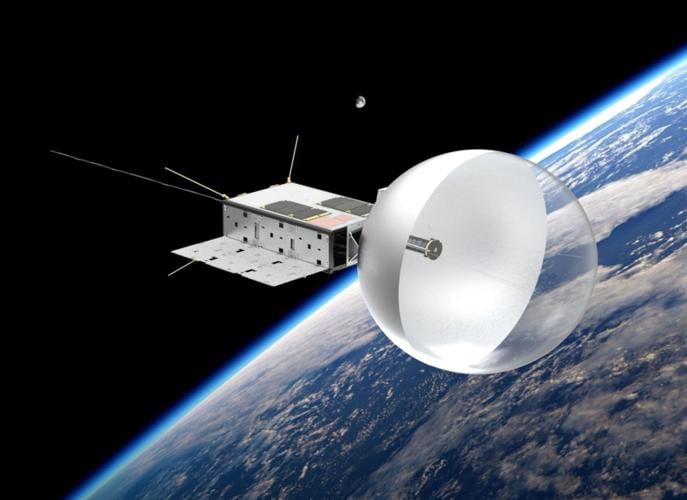

A graphic rendering of the University of Arizona’s CatSat nanosatellite with a proprietary inflatable antenna made by Tucson-based FreeFall Aerospace deployed in orbit.

Things looked good as CatSat was among eight tiny research “CubeSats” launched into low-Earth orbit aboard Firefly Aerospace‘s Alpha rocket on July 3, from Vandenberg Space Force Base in California.

But things took a grim turn when the U.S. Space Force had reported tracking eight objects deployed from the Alpha rocket during the NASA-sponsored CubeSat launch — when there should have been nine, including the launch vehicle that deployed the satellites.

As most Tucsonans enjoyed the long Independence Day holiday weekend, the team from the UA and Freefall that had worked for years to create CatSat fretted that the tiny spacecraft was lost — forever.

Lost in space?

Firefly Aerospace’s Alpha rocket launches July 3, 2024, from Vandenberg Space Force Base in California. The rocket carried the University of Arizona's CatSat nanosatellite, along with seven other academic research “CubeSats,” into low-Earth orbit.

“We didn’t hear a thing, oh my gosh, we didn’t hear anything for a long time,” said Aman Chandra, senior aerospace engineer for FreeFall, who helped develop the inflatable sat antenna while earning his doctorate from the UA. “And we were close to the point where we had started to believe that we are stuck in the rocket, we are going to burn up in the atmosphere and we’ll never hear from CatSat again.”

Firefly couldn’t confirm whether CatSat had deployed from the rocket, and the FreeFall team theorized that a trapdoor that releases the CubeSats from the rocket’s payload section may have jammed.

There was still hope, though, as the CatSat team and the operators of the other nanosatellites — a class of standardized CubeSats weighing less than 10 kilograms — searched for signals as their respective spacecraft recovered from the normal spin that is imparted on them during deployment.

“It’s very hard to communicate with the spacecraft until it has come out of that spin, so the first six to seven hours after launch, all CubeSat teams including ours, basically, we’re listening, we’re trying to listen to any signals that it might be sending if it was alive,” he said.

Tiny, solar-powered electric motors on the CatSat spin to create momentum to stop the initial spin, and later to aim the CubeSat, Chandra explained.

“And we would estimate the approximate time that CatSat would pass overhead Arizona, and listen in at those times at the frequency that we expected CatSat to be transmitting. And we didn’t get anything.”

Tense days and nights followed.

Making contact

CatSat orbits the Earth about every 90 minutes, but its orbit shifts slightly at each pass, so ground stations can only communicate with the tiny craft every six hours or so, for about three minutes at a time, Chandra said.

The CatSat team monitored the satellite from the UA’s Applied Research Building, which opened last year on the north side of campus on East Helen Street, searching for signals with a dish antenna mounted on the roof.

“The teams had been working around the clock and initially, and we weren’t even sure if we were listening at the right time. So, one of our fears was, what if we’re just not listening at the right times and the windows are passing by and we’re just not there?” Chandra recalled.

Finally, in the evening on Monday, July 15, the team’s online chat group on Discord erupted as the ground station began receiving data from what appeared to be CatSat; a few hours later, that was confirmed.

“Suddenly, we saw all telemetry (data) come in, and it was like it had suddenly come out of the dead,” Chandra said. “We were kind of certain that we were stuck and we were on the verge of giving up on it — but then things changed.”

“As of now we can regularly communicate, we’re getting telemetry data from the satellite, we’re able to charge batteries,” he said.

TOP: Aman Chandra is senior aerospace engineer for Tucson-based FreeFall Aerospace. BOTTOM: The CatSat, a nanosatellite created by University of Arizona students in partnership with UA tech spinoff FreeFall Aerospace and Tucson-based Rincon Research, packs a lot of science into a small package.

Mission just starting

While CatSat got to orbit and is talking, its mission is just beginning as the UA and FreeFall team now goes through a commissioning process to get all of the satellite’s systems up and running, expected to take a couple of weeks.

A critical upcoming milestone will be deployment and testing of FreeFall’s proprietary inflatable space antenna, which will be linked to a ground station at the University of Arizona Tech Park at The Bridges on Tucson’s south side.

Based on designs developed in UA labs by Chandra, the ultra-lightweight antenna is made of a thin membrane that can be packed into a small space and inflated with a gas mix of nitrogen and helium to a diameter of a half a meter, or 20 inches. One hemisphere is clear and the other is silver-coated inside, forming a dish-shaped mirror to reflect and concentrate signals.

With a relatively large aperture and a high-gain antenna to allow precise signal targeting, FreeFall’s system can dramatically increase the total data return and overall effectiveness of CubeSats and other small satellites, the company says.

“What we’re expecting to get is a downlink at a greater than or equal to 50 megabits per second, which should be sufficient for us to download real-time imagery, high-definition Earth imagery and in near real time, and that is kind of unprecedented for a satellite of this size and power,” Chandra said.

If successful on the CatSat, FreeFall’s antenna will be technically qualified for spaceflight for NASA and commercial space missions, under requirements followed by both the space agency and industry.

CatSat is expected to stay in orbit for at least a year before its orbit starts to decay significantly and it falls to the atmosphere and burns up, Chandra said, adding that the team plans to complete the antenna demonstrations in about five months.

“Qualifying our inflatable antenna is crucial in FreeFall Aerospace, the University of Arizona, and Tucson’s developing space ecosystem,” FreeFall Aerospace CEO Dan Geraci said following the launch. “We look forward to making this capability available for commercial, scientific and government space missions.”

FreeFall was co-founded in 2016 by UA astronomy and aerospace engineering professor Christopher Walker and NASA engineering and planning veteran Doug Stetson. The company licenses the antenna technology from the UA.

On orbit, the CatSat also will use a long whip antenna to listen to signals from thousands of Ham radio operators around the world to study the behavior of radio waves at various points in the ionosphere, the uppermost part of the Earth’s atmosphere.

The tiny craft has three optical sensors — one camera for high-resolution Earth imagery, a low-resolution sensor to monitor the antenna status, and a camera to allow CatSat to see and navigate by the stars, Chandra said.

In 2018, the FreeFall team successfully tested the inflatable antenna at 159,000 feet on NASA’s high-altitude balloon at the edge of space, though not quite in orbit.

Years-long project

The CatSat, a nanosatellite created by University of Arizona students in partnership with UA tech spinoff FreeFall Aerospace and Tucson-based Rincon Research, packs a lot of science into a small package.

A dozen UA students built CatSat over about four years with sponsorship, components and development and testing assistance from FreeFall and Tucson-based Rincon Research Corp., a 40-year-old company specializing in terrestrial and space-based data communications systems.

UA undergraduate and graduate students, including Shae Henley, Walter Rahmer, Hilly Paige, Del Spangler and Sarah Li integrated and tested the CatSat systems.

Using an off-the-shelf CubeSat chassis made by a Danish company, the UA students and staff built a camera system and a radio propagation experiment, installed the science and communications payloads, delivered the flight system for launch and led mission operations.

Under standardized CubeSat dimensions of 10-centimeter, or roughly 4-inch, cubes or CubeSat units, the CatSat is a six-unit or 6U CubeSat, weighing about 9 kilograms or about 20 pounds.

The mission was selected for the recent launch in 2021 by the NASA CubeSat Launch Initiative, which aims to help the commercial small-sat industry grow.

In addition to its technology partnerships with the UA, FreeFall has the support of local investors.

In 2018, UA Venture Capital, a Tucson-based firm that invests exclusively in University of Arizona technology spinoffs, announced a 20% equity investment in FreeFall Aerospace for an undisclosed sum.

Find more information on CatSat at catsat.arizona.edu.