Members of Golden Dawn Tabernacle know it’s not just their duty to hand over 10% of their paycheck as tithing.

That’s the minimum expectation.

Former members say they were told they owe at least 10% of everything — a business’s gross revenue, employee paychecks, gifts, anything — and are encouraged to give more.

Aaron Duenas grew up in Golden Dawn Tabernacle church but eventually left with his wife. He poses for a photo in his home in Tucson, on July 25.

“Any money that comes into your hand, no matter where it comes from, you need to give 10%,” former member Aaron Dueñas said. “If it's birthday money, 10% of that. If you found 10 dollars, 10% of that goes to him.”

The “him” Dueñas referred to is Pastor Isaac Noriega, the founder of Golden Dawn, a church near Tucson International Airport formally called Tabernaculo Emanuel. For about 50 years, he has run the 500-member church with a tight grip.

Dueñas and other former members said Noriega has an especially firm grasp on members’ tithing. Noriega even checked with Dueñas’ employer, also a church member, to investigate how much Dueñas was making and whether he was tithing the full 10%, Dueñas said.

Noriega denied doing this and said in an interview and email that how much members tithe is up to them.

But electrician and former Golden Dawn member Oscar Jacques Jr. said the pressure is strong. He recalled paying around $110,000 in tithes when his company grossed more than $1 million of revenue in 2016. Despite the windfall that year, he ended up accumulating thousands in credit card debt for regular expenses.

“Of course, I kick myself now, because I can't believe I was so stupid,” Jacques said.

Beyond the tithing, there are also collections at every service — twice on Sunday and once on Wednesday — which bring in thousands of dollars per service, former members estimated.

It’s all part of a broader money-making apparatus that some former members view as excessive or exploitative.

Volunteer labor, encouraged by church leaders, built Golden Dawn’s church buildings at South Nogales Highway and West Los Reales Road. Donated labor also built a set of duplexes on the church property that former members allege are used now as leverage to push widows out of their homes, something Noriega strongly disputes.

The church has even acted as a mortgage lender for some members, according to documents filed with the Pima County Recorder's Office.

“They’re essentially using the church as a bank,” said John Calvo, a former member who has researched Golden Dawn’s financial dealings. “That’s very questionable because they don’t do that for everyone in the church. They’re only doing it for a select few people – people who have status or people they want to help.”

John Calvo, a former member of the Golden Dawn Tabernacle browses his website, goldendawntabernacle.org, inside of his home, Aug. 10. He started the website to expose abuses of power in his former church.

In interviews and emailed questions and responses, Noriega and other church leaders denied any financial wrongdoing, arguing instead that Golden Dawn has been helping members thrive.

“I don't preach ironclad about tithings, that they gotta pay tithings,” Noriega said by phone. “I never have called — never — I wouldn't even think about calling an employer and asking them how much they make. That's ridiculous.”

He noted that the Bible says that if believers bring tithings and offerings, they will prosper. At Golden Dawn, he said, “they have prospered. They got real nice cars, they drive real nice cars. There's nobody in our church that is in poverty. Because we help and they work — they’re workers.”

Dealing in real estate

The church is not registered with the IRS as a tax-exempt charity, as many churches are. Nor is it part of a broader denomination. Golden Dawn is part of a religious movement called "The Message of the Hour," or simply "The Message," in which followers consider 20th-Century American preacher William Branham to be God's prophet.

The global members of The Message probably number somewhere in the low millions, with the fastest growing areas being in Africa. A Message organization called Voice of God Recordings puts the number of followers in the sect at roughly 3 million based on how many people receive the group's religious materials.

Noriega began following Branham as a young man in California and founded his Tucson church, then known only as Tabernáculo Emanuel, in 1973.

In a January 2013 filing at the recorder's office, Noriega checked a box categorizing Tabernáculo Emanuel as a sole proprietorship owned, apparently, by him. In a subsequent filing, made in August 2013, Noriega described the church as being run not just by him but also by his son, associate pastor Matthew Noriega, and an elected board of trustees.

Isaac Noriega

That document also specified Tabernáculo Emanuel’s involvement in “real property transactions.” Noriega has experience in finance: One of his early jobs in Tucson 50 years ago was as finance manager at a local company called Liberty Loan. Later he worked at Valley National Bank.

None of the financial moves is necessarily illegal, as the IRS gives churches broad leeway out of deference to the Constitution’s protection of freedom of religion.

“Churches are unique as charities in that they don’t have to apply for tax exemption, or file annual compliance forms,” said Eric Smith, professor of taxation at Weber State University’s John B. Goddard School of Business and Economics, in an email.

However, churches can lose their tax-exempt status for two main reasons: Intervening aggressively in a political campaign, or operating to “unduly benefit a single or small group of insiders,” Smith said via email. That’s called “private inurement.”

This goes to the heart of Calvo’s critiques about how Noriega and church leaders managed the money handed over by hundreds of members of the congregation, week after week for decades. It’s been used, Calvo alleges, to buy property that benefited Noriega, his family and insiders, as well as to deal in real estate and make loans, though most were interest-free.

Money lent to church

Noriega has said that much of his personal money was derived from the settlement of the lawsuit over trichloroethylene contamination of water on Tucson’s south side.

A self-published biography of Noriega and his late wife Lucy, completed in 2023, says he received a large settlement because of the death of his daughter Gracie from leukemia and due to Lucy’s health problems. Noriega declined to say how much money he received as a settlement.

In 1992, he bought a property in what is now the 3400 block of W. Mockingbird Lane for $150,000. In 1994, workers, some of them from the church, built the home there — a 5,600-square-foot luxury residence, now estimated to be worth around $1 million.

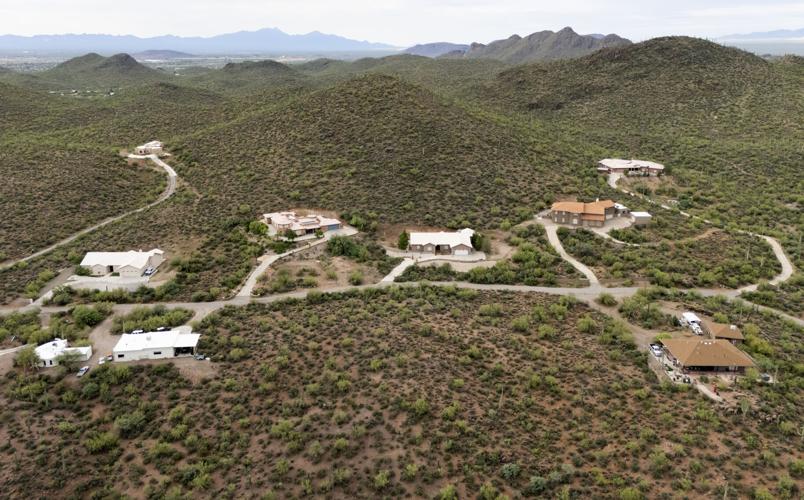

An aerial view of six expensive homes owned by the Golden Dawn Tabernacle on the edge of Tucson Mountain Park on Sunday, June 30. The religious group owns the cluster of six homes south of the pictured residential road.

This purchase became the foundation of a series of homes on that street, where Noriega, his family members and high-ranking church members have lived.

The total owned by Tabernáculo Emanuel, Noriega, family members and church leaders in the area is 28 acres over eight different properties, seven of which have houses on them.

Among those who own property there: Noriega, his son Matthew, his son Stephen, and his daughter Stacey. The average market value of the seven Mockingbird Lane homes as of Oct. 14, according to Zillow’s estimates: $914,533. The average square footage: 4,159.

Mortgage lending to members

Documents filed with the Pima County Recorder’s Office show an unusual practice at Golden Dawn — essentially, interest-free mortgage lending. Former members say, though, that sometimes loans came with strings attached.

Seven different documents, filed between January 2012 and December 2021 show loans to church members, secured by real estate, totaling about $689,098 — an average of $98,443 each. The two most recent loans documented in filings were for $119,176 and $91,249.

“Isaac Noriega is giving loans to people in the church using church tithing money and then putting warranty deeds against their houses,” said Calvo, who dug up these documents in 2022. “Essentially, (they’re) using church money to fund home mortgages.”

An expensive home owned by the Golden Dawn Tabernacle on the edge of Tucson Mountain Park on Sunday, June 30. The religious group owns six homes in a row on Tucson’s west side.

The loans recorded with county agencies weren’t the only ones, and sometimes those documents told only part of the story.

Joel Chacon, a former member of the church, said Noriega and the church elders offered to pay off his parents’ home loan in 2020 on the condition that his father not tell anybody and that he keep his kids in line.

Chacon said he and his brother were deeply into sports at the time. They would go to games, go to restaurants to watch games and use the internet and smartphones. All of that is forbidden “worldly” conduct in Golden Dawn.

About a year later, Joel Chacon said, Noriega revoked the payoff and demanded the money be paid back because Chacon and his brother were not following church rules.

“He did that to my dad to try to get me to come around,” Chacon said.

When he was forced to speak with the pastor about it later, Chacon said, “His answer to me was to quote Scripture: ‘The Lord giveth, and the Lord taketh away.”

Noriega said in an email he didn’t recall saying those words, but church leaders acknowledged the broad outline of what Joel Chacon said.

“We assisted Jacob Chacon when he lost his job and then lost another job. His sons then began using their money incorrectly after we had assisted their father,” they said in an email. “We asked Jacob to repay the loan and to ask his sons to help him with the payments since they were using their money incorrectly. Jacob agreed to repay the loan.”

Elder compound constructed

The church bought an empty lot next to Golden Dawn’s property in 1998, and leaders decided to use it for new elder housing.

But former members said the series of eight units built for widowed elders on East Elvado Drive also turned into a money-making center for the church.

The construction of the duplexes was largely through donated labor, former members said. They hesitate to call it “volunteer” labor because it was essentially mandatory for some, especially those working for contracting companies whose owners were church members.

“The people who worked for one of the brothers at the church — they were more or less required to show up,” said Gabriel Cordova, who worked on the project but left the church in 2022.

Gabriel Cordova, posing for a photo in his home in Tucson on August 14, and his wife Zoe were members of the Golden Dawn Tabernacle church until two years ago.

As the housing units were completed, pressure was applied to move widows in and sell off their houses, some of the proceeds then going to the church, Calvo said.

Esther Jacques said Noriega suggested she and her husband, head deacon Isaac Jacques Sr., should move into the duplexes. They declined, but Noriega suggested it again after her husband died in 2013, Jacques said.

“After he passed away, then he (Noriega) started putting pressure,” Jacques said.

The idea, she said, was that she would sell her house, then give the proceeds to the church and live in the elder housing without paying rent. But she was skeptical in part because the area is all paved, with no dirt for putting plants in the ground.

“He told me those places are nicer than mine, yet he wouldn’t let me go over there and check for myself,” Jacques said. “I wouldn’t be able to go there and see it till I said ‘Here’s the money, now I can move in.’ There was no way he was going to let me see the house.”

She stayed in her own home, living with her unmarried daughter, but after leaving the church, her daughter stopped speaking to her, Jacques said. Eventually, she sold the house and split the proceeds, with her daughter donating her share and moving into the duplexes.

In response, Noriega denied pressuring Jacques and accused her of her own financial improprieties.

Struggle over elderly widow

In another case, a former member caught what was going on with his elderly mother and intervened.

An expensive home with shuttered windows owned by the Golden Dawn Tabernacle on the edge of Tucson Mountain Park on Sunday, June 30. The religious group owns six homes in a row on Tucson’s west side.

George Gonzales had left the church years before when, in 2006, he realized his mother Trina had been moved out of her house and into the widows’ compound, he said. He wasn’t up to date on his mom’s affairs, Gonzales said, because the church prohibited her from speaking with him, although he checked on her occasionally.

In general, church members are told not to interact with people outside the church, including family members who have left.

“One day we found out that they were about to take her out of the house,” Gonzales said.

Her nephew Michael Ramirez, a top church official, had obtained power of attorney and was preparing to move her to the elder housing and sell the place.

“I know mom would have done anything the church told her to do,” Gonzales said.

Within a couple of months, he said, “They had moved everything out of the house. It was totally empty. They were in the process of selling it.”

In an email, church officials described the situation differently. They said Ramirez and his mother (Trina Gonzales’ sister) “were concerned family members when they found Trini Gonzalez (sic) living in squalid conditions with no food, utilities, and without care for her dementia.

“Michael and his mother attempted to care for her but were hindered without power of attorney.”

George Gonzales and other family members outside the church were angry when they found out Ramirez had obtained power of attorney and moved her out. For one thing, they couldn’t even reliably visit their mother.

“Sometimes, we’d go over, they’d shut the gate, and they wouldn’t let us go in,” he said.

An aerial view of six expensive homes owned by the Golden Dawn Tabernacle on the edge of Tucson Mountain Park on Sunday, June 30. The religious group owns the cluster of six homes south of the pictured residential road.

But besides that, they didn’t believe that Trina Gonzales was of sound enough mind to sign over power of attorney. She had received a diagnosis of dementia in previous months.

So, Gonzales filed a petition for guardianship in Pima County Superior Court. Ramirez, his cousin who was a church trustee, filed an objection, arguing that she was “of sound mind and is capable of taking care of herself.”

But Ramirez eventually dropped the objection, and George Gonzales became his mother’s guardian. She moved back to her old house, the church brought back her belongings, and the court monitored her finances.

“If my sister hadn’t had proof that we took her to the doctor and that she had early stages of dementia, we never would have got her back,” Gonzales said.

In an email, church leaders said, “This matter had nothing to do with the church or Michael Ramirez’ official capacity as a trustee of the church.”

‘Volunteer’ efforts built church

From the earliest years of Tabernáculo Emanuel, in the 1970s, each church building and other construction projects have been carried out through the donated efforts of members. Church leaders have encouraged working in the trades over the years, so there has been plenty of internal expertise to draw on.

But former members say as time went on, the effort became less voluntary and more compulsory.

They completed the first church in 1975, the second sanctuary, seating 750 people, in 1992, and the latest, seating 1,000, in 2015.

Noriega’s biography describes the members’ work on the second church building this way: “Throughout the entire construction project, the brothers tirelessly labored countless hours, often working into the early hours of the morning in order to complete the tabernacle as quickly as possible.

“It was the preaching of the Word that encouraged and motivated the brothers to keep working.”

Projects such as the third tabernacle were even more involved than they seemed, as they also included renovating the old sanctuaries, re-working parking lots and other ancillary jobs, Aaron Dueñas said.

An aerial view of the Golden Dawn Tabernacle at 301 E. Los Reales Rd. on Sunday, June 30.

Dueñas recalled his father waking up early to go work his landscaping job, coming home, parking his car, and going to work on church projects without showering or eating. Even then, Dueñas said, Noriega often wasn’t satisfied.

“You go to help on a church project, but in between you’re still going to church. You’re going to church three times a week,” Dueñas said. “The whole service becomes about this church project and how people aren’t dedicated enough, which means that they must not be dedicated enough to the Lord, which means you must not be saved.”

Noriega called this description of his criticism “unequivocally false.”

The work Dueñas did as a teen and young man on church projects could end up benefiting Dueñas, who left the church in 2022. He was brought to the country from Mexico on a tourist visa as a child and never had legal status to live here.

Upon completing school, he would have been eligible for the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, but he attended the church’s homeschool program and got a diploma that was worthless for DACA purposes.

Now, Dueñas' lawyer is pursuing a visa for him on the basis that he was trafficked for labor. The application is pending.

Requiring tithes disputed

Noriega learned early in life the importance of tithing for a pastor’s survival. His father, Clemente Noriega, led an Apostolic church in Selma, California, as the biography of Noriega and his wife explained.

“Brother Clemente could not depend on the tithing money from the people he pastored because the Apostolics did not faithfully tithe as commanded in the Scriptures. In fact, many would withhold paying their tithe as a means of manipulating their pastor: If they did not agree with what he was preaching, they stopped paying.”

When Noriega became pastor, he made tithing at least 10% an ironclad rule, former members said.

“Isaac Noriega will publicly call out people if they are not paying their tithes,” John Calvo said. “He cares about it so much.”

In an email and interview, Noriega denied mandating tithes.

“In 50 years of ministry, there has never been a requirement for tithing. As a Biblical principle, congregants give from the heart as they desire.”

A view of the Golden Dawn Tabernacle at 301 E. Los Reales Rd. on Sunday, June 30. Twenty former church members have described the community as a "cult."

Some in the evangelical Christian world don’t agree with a strict interpretation of the Scriptures about tithing. Carl Williamson, an assistant professor of discipleship and church planting at Harding University in Arkansas, said it’s a good idea for church leaders and members to talk about money and their ability to give.

“I personally do not believe that churches should require tithing of 10% from members,” Williamson said via email. “In the Old Testament, there was a spoken requirement for giving a percentage of salary, but it was never required as a draconian practice.”

“I believe this misses the Bible’s call for us to willingly give out of our means. Personally, I train my children and others to begin with 10% of their finances, but I would not suggest church leaders go back to the ledger and then question members about their spending.”

Golden Dawn member Pedro Zúñiga defended Noriega’s practices as Biblical.

“If you can’t at least give 10% to God, you've got to check your heart,” he said. “Just because you give 10% doesn't mean you still can't give additional money, if you see your neighbor in need. Ten percent is just the starting point.”

Citing the Bible, Zúñiga went on to defend Noriega’s use of the money.

“Once you give tithing to somebody, it's up to that person's discretion,” he said. “I would hope they use most of it for God's work. But even if they don't, it's still their money.

“And I believe that God will hold you responsible for what you do with your money, just like he's gonna hold me responsible for what I do with the 90%.”

Demand goes unanswered

Oscar Jacques Jr. got fed up in 2022 after finding out about the 2013 document that described the church as a sole proprietorship. He started wondering, he said, whether he’d been tithing to a for-profit entity, and what the tax implications were for his business.

He had also borrowed $53,000 from Noriega, he said, and was wondering what that financial entanglement could mean. So he and a bookkeeper friend drew up a letter demanding more information.

“I am formally requesting an official tax statement for the years 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019 and 2020 for all donations presented to Isaac Noriega DBA Tabernáculo Emanuel, LLC,” he wrote. “Unless these documents are presented and all allegations are cleared, I will not resume payments on the outstanding loan of $25,859.03.”

He never got the information, he said, so he stopped paying on the loan and left the church. In the end, he said, it felt like a “racket.”

“They're almost like mafia, mafia members that just use ‘God.’”

Expensive homes owned by the Golden Dawn Tabernacle on the edge of Tucson Mountain Park on Sunday, June 30. The religious group owns six homes in a row on Tucson’s west side.