With more than 20,000 near-earth asteroids, some of which pose potential threats to our planet, many astronomers have been tasked with identifying, tracking and estimating the potential impact of these objects.

But what happens if an asteroid really does come crashing into earth?

In 2017, the University of Arizona, along with NASA’s Planetary Defense Coordination Office, led an international team of astronomers to successfully complete the first campaign to test the global response to an asteroid threat as part of the International Asteroid Warning Network.

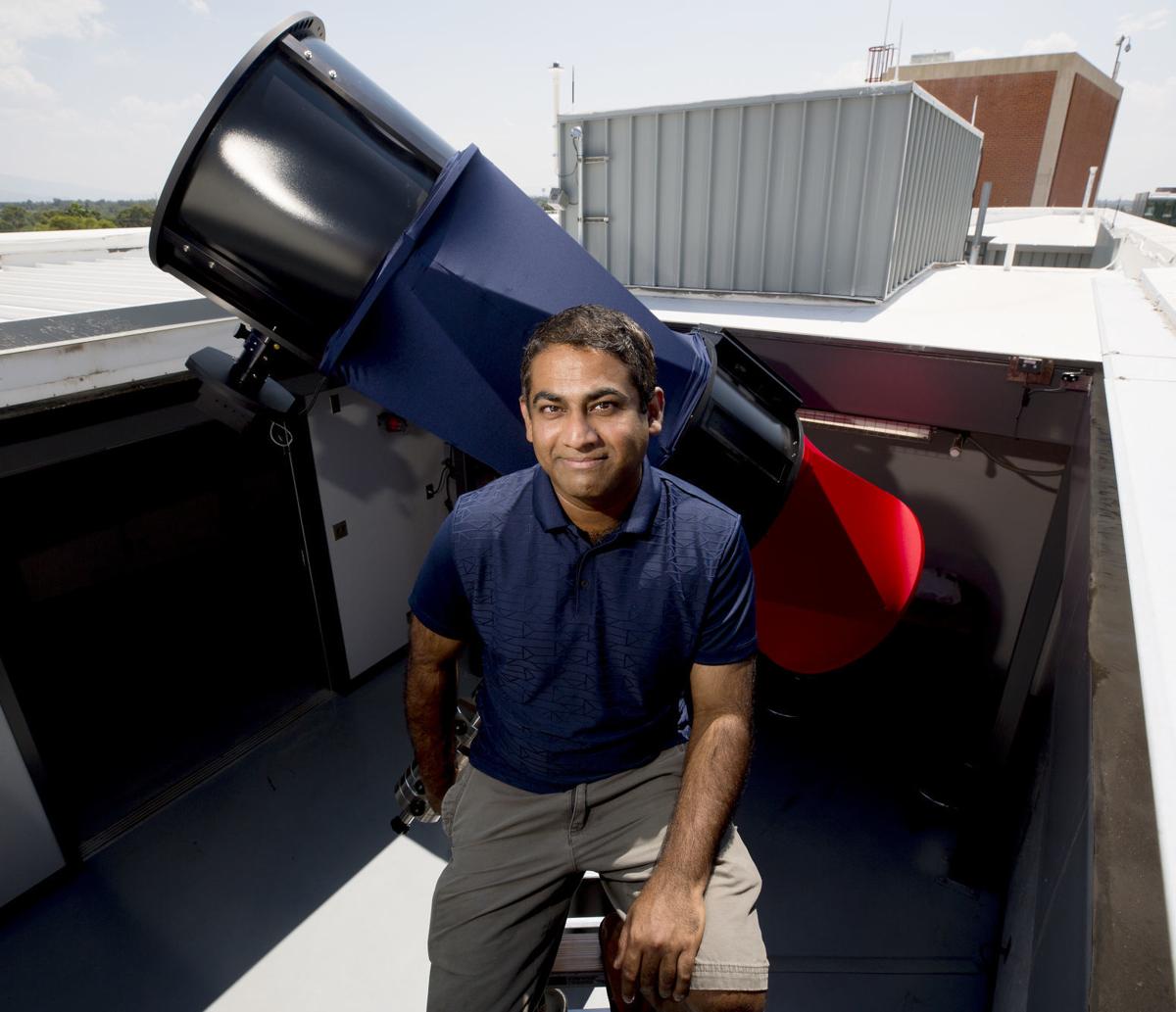

Using a real asteroid, Vishnu Reddy, an assistant professor of planetary sciences at the UA’s Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, led a team of 70 scientists from 14 different countries to find, track and characterize a real asteroid. They also used telescopes from all over the world, including the UA’s Catalina Sky Survey and Spacewatch telescopes.

According to Reddy, with so many other natural disasters that occur much more often, sometimes these types of threats can be overlooked. In the case of a hurricane, for example, scientists can use data and information from previous hurricane threats to learn and build more effective safety measures, but this isn’t as possible for asteroid threats.

“That opportunity is not there in the case of asteroid impacts because they are so rare, but we still need to be prepared for them because they could be potentially devastating,” he said.

The real goal of this exercise was to test the planetary defense system using a real-world example, which included observations, modeling, predictions and communication. More specifically, the team aimed to gauge the response of people who are directly responsible for ensuring that an asteroid threat is handled properly. Reddy and his colleagues wanted to see how scientists, astronomers and government officials would react and how well they would communicate with one another in real time.

The 2012 TC4 asteroid, estimated to be 60 feet across, was expected to make a close flyby of earth in October 2017 at a distance of just over 4,200 miles.

The team was able to locate the asteroid in July 2017 and began to study its orbit, rotation, shape and composition. They found that this particular asteroid was spinning once every 12 minutes and also tumbling over several axis points.

When it came to studying its shape, the team commissioned the Arecibo Observatory telescope in Puerto Rico and the Green Bank Telescope in West Virginia to help. Unfortunately, in September 2017, another natural disaster, Hurricane Maria, destroyed the Arecibo Observatory’s main dish. The team then turned to the Goldstone Radar in California to get the data they needed.

With the information collected from the telescopes, they found the asteroid was actually only half the size they anticipated.

“It turns out that this asteroid is made up of a particular type of meteorite that is very rare and it reflects about 50% of light,” said Reddy. “And that’s the reason why it was so much smaller than we thought.”

As soon as the team knew everything they needed to about asteroid TC4, they began to develop a plan of action and treated the object as a potential impactor.

Reddy said that for this initial exercise, announcements and notifications of an asteroid threat were sent all the way to the White House, starting as soon as the real threat could have been detected in July 2017 and preparing for potential impact in October 2017. It was important, he said, to be able to test this line of communication between astronomers, policymakers and stakeholders within the government, not just in the United States, but other countries as well.

“It was remarkable given the amount of people that we had working on this campaign,” said Reddy.

Under protocol from NASA’s Planetary Defense Coordination Office, if the potential impact of a near-earth asteroid is greater than 1%, a notification must be sent through the proper channels. In this exercise, the office was notified by astronomers of the threat and a planetary defense officer determined the need for a notification based on the asteroids size, distance and trajectory. The office notified a NASA administrator and then contacted the Executive Office of the President.

If a real asteroid impact was expected, notifications would then be sent to other federal agencies, such as the Department of Homeland Security and Congress, as well federal, state and local emergency response organizations. If the impact were outside the United U.S., the State Department would be responsible for notifying the affected region. Lastly, NASA would release a statement to the public.

“Understanding and knowing the communication protocols is important,” said Reddy. “This is ultimately a civilian exercise. It’s not like we have military-style communication lines or backup lines. What we realized is that it’s going to be messy, but it will definitely work.”

While communication can always be better, Reddy said he is happy with how this first exercise turned out. In reflecting on the TC4 campaign, the team also hopes to decrease its asteroid characterization in time to get information about the asteroid faster, leaving more time for preparation from the moment notifications are given to when the impact happens.

After completing the first global exercise, the team has since moved on to a second exercise, this time focusing on asteroid KW4, which flew by the Earth at 3 million miles in May. In this scenario, with an asteroid that is much further away, the team is looking to study the potential impact of a binary asteroid, which is a system of two asteroids that revolve around each other at close range.

“There will always be another scenario,” said Reddy. “Next time we may pick an asteroid that has a triplet system or an asteroid that is larger than what we’ve been working on. It’s also good to keep people talking and communicating and collaborating. We want to continue to exercise that system.”