Among Tucson’s many streets named for famous American writers is one honoring John Greenleaf Whittier.

His best-known poems, including “Snow-Bound: A Winter Idyl,” are still well read today.

Lesser known, perhaps, is that Whittier was once a leading voice against slavery in the United States.

In 1833, he published his scorching antislavery pamphlet “Justice and Expediency.” In one powerful passage, he described American bondage at that time:

“A system which holds two millions of God’s creatures in bondage — which leaves one million females without any protection save their own feeble strength and which makes even the exercise of that strength in resistance to outrage, punishable with death — which considers rational immortal beings as articles of traffic — vendible commodities — merchantable property — which recognizes no social obligations — no natural relations — which tears without scruple the infant from the mother — the wife from the husband — the parent from the child.”

Whittier had been born into a Quaker family, on a farm outside of Haverhill, Massachusetts, in 1807. During his youth, he received a limited education but became an enthusiastic reader of British and Scottish poetry, particularly Robert Burns (namesake of Tucson’s Burns Street), whose descriptions of rural life seemed to appeal to the future writer.

In 1826, Whittier, then 19, submitted his poetic work entitled “The Exile’s Departures” to the Newburyport Free Press in Massachusetts for publication.

The editor of this newspaper at the time was abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, who, after seeing the teen’s poetic skills, asked him to submit other poems and also encouraged his learning, writing and active participation in the movement to end slavery in the country.

While Whittier’s home state of Massachusetts had been the first colony to legalize slavery among the 13 colonies, it was now an epicenter of the abolition movement.

Under the auspices of Garrison, Whittier began working in journalism, editing newspapers in Haverhill and Boston. By 1830 he had become editor of the well-known New England Weekly Review in Hartford, Connecticut, the leading organ of the Whig Party in New England. He also continued to write on his own, which the following year led to his first book of poetry, “Legends of New England.”

His time at the New England Weekly Review was short-lived. A failed romantic relationship, poor health and disheartenment led to his resignation and return home to Haverhill.

He believed that his lack of literary recognition was due to his personal vanity and decided to commit himself to using his writing ability to help others rather than just himself.

He adopted Garrisonian abolitionism and, for a period of about 10 years, he likely was the cause’s most influential writer.

He served one term in the General Court of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, the state’s legislature, gave speeches at antislavery meetings and edited The Pennsylvania Freeman newspaper (1838-1840) in Philadelphia.

By the 1840s, Whittier had severed ties with Garrison because he felt the best way to end slavery in the United States was through gradual changes accomplished by political methods, while Garrison wanted immediate emancipation of all slaves.

John Greenleaf Whittier on a 2-cent stamp.

After having a physical breakdown, Whittier stopped his active involvement in the abolitionist movement and moved in with his family in Amesbury, Massachusetts, to recover his physical health.

During the next two decades, he published several volumes of verse, including “Lays of My Home” in 1843, “Voices of Freedom” in 1846, “Songs of Labor” in 1850 and “Home Ballads and Poems” in 1860. One of his best and most well-known poems was “Maud Muller” in 1854. He also contributed one novel, “Leaves from Margaret Smith’s Journal,” to the body of American literature.

Following the Civil War and the ratification of the 13th Amendment, which ended slavery in the United States, Whittier changed the focus of his writing to depict nature and rural scenes.

In 1866, he published his most famous verse, “Snow-Bound.” His later collections of poetry included “The Tent on the Beach” in 1867, “Among the Hills” in 1868, and “The Pennsylvania Pilgrim” in 1872.

His 70th birthday dinner was attended by close to every well-known American writer in the country, and his 80th birthday was an occasion for national celebration. He died in 1892.

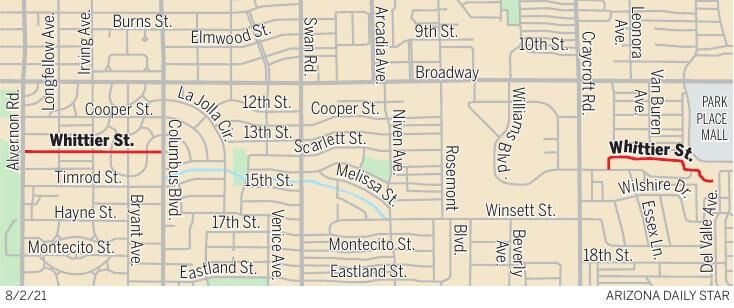

Tucson’s Whittier Street was named by John and Margaret Roberts in 1927 in their Country Club Heights, South Side, subdivision, along with other streets named for poets and writers such as Paul H. Hayne (Hayne Street) and Henry Timrod (Timrod Street). Whittier Street runs between Alvernon Way and Columbus Boulevard, and is across the street from Randolph Park.