The quirky tale of Tucson’s first unofficial zoo began in 1955 at the city’s Sewage Treatment Plant.

Edgar O’Neal Dye, a 1941 Tucson High School graduate, a World War II vet and a 1950 graduate of the University of Arizona with a degree in agricultural chemistry, became superintendent of the plant that year.

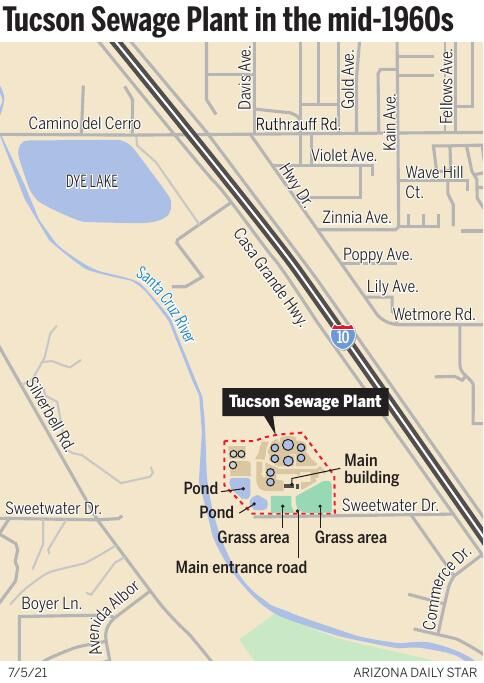

Dye, known as Neal, soon decided he would begin a beautification program on the south end of the 40 acres, northwest of Tucson at the time, that comprised the city plant near the main building. His staff obtained trees, bushes, flowering shrubs, Bermuda grass and whatever else they could get from the park system nursery located at Randolph Park (now Reid Park) to plant the 10 acres.

In order to irrigate his new plants, he used some of the effluent water from the plant. Soon after, the grass grew to as high as 4 feet tall and was very thick. The giant grass also hid dangerous creatures such as snakes.

In order to deal with the thick grass, the staff waited until fall and set the dry grass ablaze, but after burning down a couple trees, as well as a few telephone poles in the process, they decided to call the parks department and have mowers brought in. The mowers were less dangerous than fire but often struggled to cut through the thick, matted grass, and because of the limited amount of mowers and the distance to the plant, they rarely made it out there.

So in 1957 or 1958, Dye heard the UA was selling 13 sheep, and he filled out a city requisition form to purchase them. On the form, he put 13 “rambouillets” (which is a type of sheep bred in France), probably to get the requisition form approved without many questions. It was approved because the city purchasing agent believed it was hydraulic equipment. Dye spent city money to purchase the sheep and therefore created the first unofficial city zoo in town, which came to be called the Dye Zoo or Dye Farm.

Dye, who had never owned sheep before, soon learned that the sheep could not be trusted to wander around the grassland of the plant safely, and they commonly jumped into the ditches, breaking legs. The staff had to fence sections of the lawns and pen the sheep in.

After things were set up for the sheep, Dye realized the grass was still growing faster than the current animals could eat it. He came up with the idea of taking in unwanted animals such as horses, cows and goats to join his grass-eating team.

Edgar O’Neal Dye, right, superintendent of the Tucson Sewage Treatment Plant, is shown in 1960 with Emil Krall, the Phoenix contractor who constructed the $1.2 million expansion.

Since it was around Easter time, he also conceived the idea of soliciting rabbits and chickens that had been given as gifts but were no longer wanted. Both the Arizona Daily Star and the Tucson Daily Citizen newspapers ran ads offering a home at the plant to these animals.

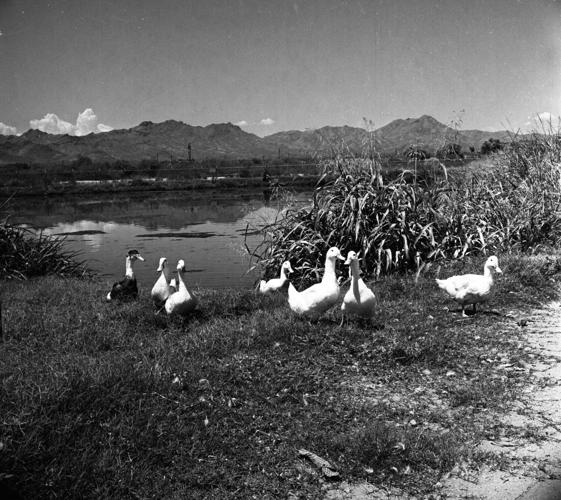

By October 1959, Dye’s Zoo had 19 sheep, 12 ducks, 12 chickens, two rabbits and two geese. It also had at least one chlorine pond but likely two ponds by this point.

In August 1961, after a flood hit the Santa Cruz River, some of the plant staff found a pool near the river that contained carp, and brought about 25 of the young fish to deposit in one of the plant’s ponds. This rare occurrence of finding fish in or near the normally dry river caused the newspaper to cover it.

By 1962, the flock of sheep counted about 80, and the wool from these animals was used in exchange for food to help feed the plant critters, creatures and beasts. Included by this time were pheasants, peacocks, armadillos, an Egyptian goose, donkeys (one named Duncan), a monkey (Maurice), a calf (Clarence) and a baby alligator.

Edward Dye, son of the plant superintendent, recently recalled: “I remember that in the mid-1960s, we got a 3-foot alligator from the sewage plant since it wasn’t working out there. We kept it in the backyard of our house, in an isolated corner. No visitors were allowed to come over and see it. I also recall one day my father fed a whole chicken to it which he swallowed whole to my amazement. Dad, after a short time, found a suitable home for it.” It’s likely this alligator is the same one that was at the plant in 1962.

Later in 1962, Dye, along with his boss, Herman Danforth, director of the Public Works Department, designed a new, approximately 40-acre, 5-foot deep, effluent regulating pond, to be built about a mile north of the main sewage facility. The state of Arizona was planning to construct a freeway (I-10) nearby the following year and had agreed to take gravel from the location of the planned pond and create the hole for it.

In 1963, the Egyptian goose, called Cleopatra — by this time one of 600 animals and birds at the plant — became the center of media attention when she laid five eggs at her nest, but a couple of months later, all attention faded as the eggs never hatched.

Around the same time, the city sewage division was transferred from the Public Works Department to the City Water System.

Later that year, a letter to the editor appeared in the local paper suggesting Dye and Gene C. Reid, head of the Tucson Parks and Recreation Department, work together to create an official children’s zoo at the sewer farm.

It said Dye “has done a wonderful job in managing the plant and with little or nothing has the start on a children’s zoo. All of the animals up to now have been gifts to the farm. ... Gene Reid has done a wonderful job with our city parks, and I am sure he and Mr. Dye could work out a wonderful park and children’s zoo with a very small cost to the taxpayer, plus the cooperation of our citizenry.”

While that didn’t happen, a couple years later Reid did start the Randolph Park Children’s Zoo, now Reid Park Zoo.

In 1970, Pete Cowgill, a reporter for the Star, wrote about the Dye Zoo: “This is the original city zoo. Gene Reid’s first stock of birds and animals at Randolph Park came from Dye’s Farm.”

While the first part is correct, because Dye used city funds to buy the first 13 sheep, the second statement is likely incorrect since the first animal believed to have been donated by Dye to Reid’s new children’s zoo was one monkey, and after Reid already had a few animals.

In 1976, Dye received an award from the Tucson Audubon Society for having over the years developed his wastewater plant into a haven for all kinds of birdlife from grackles and mourning doves to ruddy ducks and northern phalaropes.

The society was particularly pleased with Dye Lake, a 42-surface-acre pond that had originally been designed in 1962 by Dye and his boss, located just south of El Camino Del Cerro (Hill Road) and just west of I-10. It was a haven for birdwatchers of all kinds.

In 1982, when Dye retired, the Dye Zoo was disbanded, and the “mowing machines” were donated to the 4-H Club and Future Farmers of America.

Edgar O’Neal Dye died in 1989. While he ran a tight ship at the plant and won a few awards for his job, he will likely be remembered for having saved hundreds of unwanted animals from unhappy lives or death.