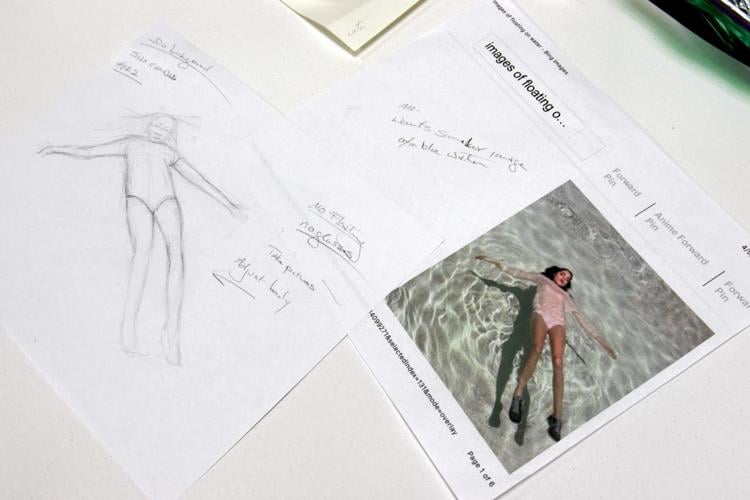

Michelle Buscemi enters the art studio ready to work on her latest painting. Her teacher takes out the sketches. In one, a woman floats in calm waters. Buscemi says the woman is her.

“I want people to understand my wheelchair is not me,” she says. “My wheelchair’s a tool. It’s not who I am.”

Buscemi’s creative vision involves a body of water. Her teacher mixes paint until the artist tells her she has the right tone of color.

Buscemi, also known as Mo, has cerebral palsy and limited mobility. She translates her creative vision onto a canvas with the help of “trackers” in the Laser Art Technique program at Arts for All.

The nonprofit focuses on access to creative programs for people who have low incomes or disabilities. Tracker and art teacher Harriett Morton helps students with limited mobility manifest their opuses.

Morton has students she has worked with for over a decade. Some of them communicate through movement rather than verbally. As long as they can convey yes and no, she can translate their artistic vision.

“From a yes and no, you can do anything,” she says. “I know their body movements. I know their sounds.”

Student Brent Quihuis, right, communicates nonverbally with movements that signal yes and no. He’s been working on his current painting for more than six months.

One way they communicate is through custom headgear with a laser on it, which Morton has improved over the past decade. They move the pinpoint red light over the canvas, and Morton tracks it with a pencil.

“The only thing that I am is a brush,” she says. “It’s not until they literally feel that, that we’re where we need to be.”

Morton begins the process by sitting down with her students and discussing their artistic concept. That is often followed by a sketch. The students explain what they want to paint, and Morton will research and come back to them with visual examples to choose from.

On the table, next to a blank canvas, are printouts of water images. Buscemi decides she wants water that looks like a natural body rather than a pool. Morton mixes white into blue paint little by little until Buscemi tells her she has the right tone.

“It’s really not anybody doing it for me,” Buscemi says. “They’re helping me facilitate what I want to do.”

Another longtime student, Brent Quihuis, who has cerebral palsy, communicates nonverbally with movements that signal yes and no.

Art teacher and direct support professional Matt Katz is also a tracker at Arts for All and started working with Quihuis seven years ago.

Aware of their different skills, Quihuis uses the two trackers like different paintbrushes.

“You have to be patient,” says tracker Matt Katz. “You have to be a good listener — an active listener.” Here, he follows a laser pointer dot placed by student Brent Quihuis.

He’s been working on his current painting for over six months. On one edge are his hands, traced onto the canvas. There’s a section in the middle where he physically put his hands in the paint to create texture. On the right side, Katz refers to a sketch, and with Quihuis’ direction, transposes it onto the canvas.

Wearing the laser cap, Quihuis moves his head and the corresponding red dot is on the canvas. He creates a line like the edge of a continent on a map. Katz follows with a pencil, always asking if he’s drawing it correctly.

After several very deliberate lines, Quihuis requests some adjustments, and they have the beginning of what will become branches and roots.

“You have to be patient,” Katz says about being a tracker. “You have to be a good listener — an active listener.”

Working with a student who’s nonverbal can take longer to get the artistic vision right, but the trackers don’t ever want their students to settle. Sometimes a student will communicate that a line the tracker just made looks horrible. And they redo it until it’s right.

A laser pointer mounted to his red helmet, Brent Quihuis, who has cerebral palsy, positions a red dot for “tracker” Matt Katz, right, to follow. Art teacher Harriett Morton is at left.

Artists with disabilities are a group that many don’t see, but they’re a courageous voice that needs to be heard, Morton says. People often see someone in a wheelchair and don’t have any idea what they are capable of. They’re her teachers.

“They’ve changed the way I see artwork,” she says. “They’ve changed the way I do artwork. I’ve never met anyone as brave as some of our artists.”

LAT is based on a technique created by Tim Lefens called Artistic Realization Techniques. About 15 years ago, Arts for All executive director Marcia Berger invited Lefens out to teach the technique to their art teachers. They’ve since modified it into what it is today. Morton and Katz currently have seven students they track for, a number which fluctuates.

“It takes a very special person to be a tracker,” Berger says. “When people work with people with disabilities, many people have the idea they need to control the environment.”

What Berger tells all her art teachers is “teach, don’t do.”

“It’s allowing that person to be who they are and to express who they are,” she says of her students with disabilities.

Quihuis does one-hour LAT sessions two or three times a week. He says it’s been therapeutic and has had a positive effect in all aspects of his life. It’s helped him share his voice.

When his father was ill with Lou Gehrig’s disease, Quihuis did a painting in his father’s honor. Inspired by Frida Kahlo’s “Portrait of Luther Burbank,” he worked with trackers to paint his father’s likeness, with the lower half of his body becoming tree roots entwined around a body buried in the earth.

Quihuis finished it a few weeks ago, the day before his dad died. At Quihuis’ insistence, Morton got it mounted and framed the next day, so he could give it to his mother the day she lost her husband — to tell her he loves her.

Everyone has anguish, and painting is a release, Morton says.

“Everyone should have the right to home in on those feelings,” she says. “Brent is fearless. He’s taught me how to listen, how to understand, how to not give up, because he doesn’t ever give up.”

Buscemi paints her grief as well. She painted to cope with the death of her parents, who died in 2013 and ’14, within a year of each other. And she painted to cope with the death of her best friend. Her paintings often feature hearts, which have become more visceral over the years, going from cartoonish drawings to images of realistic human hearts.

She recently painted a piece to cope with a failed relationship—a dark tornado with two human hearts caught in the fray. She also created a dance piece that’s paired with it, as part of Arts for All’s dance ensemble.

“I think it got the message across,” she says. “Sometimes your life is calm. Sometimes it can blow up in your face.”

Buscemi sits on the Arts for All Board of Directors and does community outreach. She and Morton painted during an event in March put on by City Councilman Steve Kozachik to reinforce the importance of federal funding for the arts.

“This program absolutely shows the compassion and heart that just fills this community,” Kozachik says. “The Arts for All people are the brushes. They are the extension, physical and spiritual extension of the artists, whether it’s in paint or it’s in dance.”

Quihuis has painted his grief — doing a painting of his father when his dad was ill from Lou Gehrig’s disease.

During the 14-year span in which Buscemi has learned to paint and dance, she’s also learned not to be afraid of failure. If something doesn’t work out, but she just keeps trying.

“I know there’s no boundaries because I can’t physically do something,” she says. “I don’t use that as a crutch.”

“Don’t let your disability stop you. There are plenty of ways to be what you want.”