This story was made possible by a grant awarded to La Estrella de Tucsón by Solutions Journalism Network, an organization dedicated to promoting journalism that analyzes community responses to specific problems.

Affordable, high-quality child care has become out of reach for more than 90% of Arizona families, with Hispanic women facing an even steeper challenge to obtain those services due in large part to an insurmountable wage disparity.

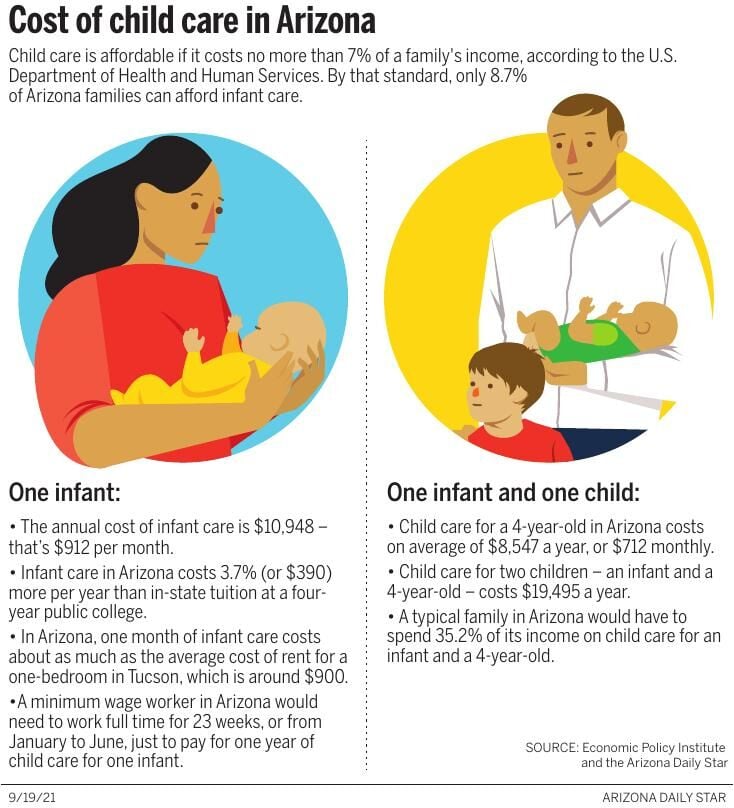

Child care is affordable if it costs no more than 7% of a family’s income, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. By that standard, only 8.7% of Arizona families can afford infant care, financial experts say.

Research by The Economic Policy Institute, an independent, nonprofit think tank, shows that child care is unaffordable for typical families in Arizona, and completely out of reach for minimum wage workers, who make $12.15 per hour. In 2019, Tucson’s median household income was $43,425, substantially lower than the state’s median household income of $58,945, according to the most recent census data.

The average annual cost of infant care in Arizona is $10,948 — 3.7% more per year than in-state tuition at a four-year public college. Child care for a 4-year-old costs $8,547 per year, meaning a typical family in Arizona would have to spend 35.2% of its income on child care for an infant and a 4-year-old, according to the EPI.

And with Latinas facing a sizable wage gap, an already difficult cycle becomes vicious, Tucson Mayor Regina Romero said.

“The less money we get in our pockets, the less high-quality preschool we can afford,” Romero said. “There are deeper structural barriers that we have to dismantle in order to have better education outcomes and better economic outcomes.”

While Arizona isn’t the most expensive state in the country in terms of child care (it costs more in states where the cost of living is higher, with Massachusetts topping out at more than $20,000 per year,) it is one of 33 states where infant care costs more than college.

EPI senior economist Elise Gould said that for decades, the narrative centered around the individual failings of families who were unable to afford child care, but the tide has since turned.

“People now realize that it’s a pretty widespread problem, it isn’t just a low-income problem,” Gould said. “I think in the last few years, it’s really come to the fore in the national discourse.”

Over the last four or five decades, hourly wages have grown incredibly slowly, meaning in part that households have needed parents to work more and more, causing the demand for child care to increase, Gould said.

“When you think about what it really costs compared to how much people make, it’s just eating away a huge amount of their budget,” Gould said. “In a lot of ways, child care is way too expensive for many families, but the flip side of that is that often times, it’s actually not expensive enough.”

In an interesting twist, child care workers are often unable to afford child care of their own. Nationwide, the families of child care workers are more than twice as likely to live in poverty as other families, and a median child care worker in Arizona would have to spend nearly half her wages to put her own child in infant care, according to the EPI.

“Those child care workers are some of the lowest paid workers in our country,” Gould said, adding that as long as child care workers receive such low pay, those jobs will continue to remain vacant, resulting in wait lists and a shortage of high quality child care options. “If you want high quality care for your kids, you’re going to have to pay for it.”

Gould said it’s important to recognize that child care workers in the current economy are undervalued.

“They’re undervalued for the kind of work they do, they’re undervalued because of who they are,” Gould said. “Something like 90% of child care workers are women. Many Black and brown women, many immigrant women. Some of those wages reflect the value society has placed on that type of work and those workers themselves.”

High demand, low supply

While the lack of affordable, high-quality child care is a nationwide issue, Arizona has faced some distinct challenges over the years, said Michelle Saint Hilarie, senior statewide program director of Arizona’s Child Care Resource and Referral.

Hilarie, who has worked at AZCCRR for 20 years, said that for the first time in her tenure, the state’s Department of Economic Security is doing a tremendous job in terms of innovating and securing new partnerships with community groups to administer programs and services and create more options for families. This includes the colocation of DES staff within different organizations to meet clients on-site, at places they’re already going to receive services.

Hilaire said Arizona was already in a downward spiral prior to the pandemic, with the number of certified family child care providers — people who care for up to four children in their homes — at an all-time low.

“Working families don’t work traditional hours as commonly anymore, so the need for nontraditional care, 24/7 availability is in really high demand, and there’s almost no supply for that,” Hilarie said, calling it a chronic issue.

Complicating things is the lack of workforce to fill child care vacancies, Hilarie said, pointing to a recent survey by the National Association for the Education of Young Children that said in Arizona, 84% of child care programs reported not being able to find employees.

“Forever our problem was we had tons of child care and a huge waiting list for financial assistance, and families couldn’t get the care they needed because they couldn’t afford it,” Hilarie said. “Now, we have families who need care who can get assistance, and there’s no child care available.”

In addition to the lack of affordable, high-quality options for infants and day care-aged children, Hilarie said that a lack of before- and after-school programs is creating additional difficulties for parents of kids in kindergarten through sixth grade.

Hilarie called the recovery efforts “really, really hard,” but said that there are some incredible initiatives in the works.

AZCCRR runs a website in both English and Spanish and a phone line that helps Arizona families find affordable child care that fits their budget and schedule. They run a state database of all licensed child care centers, connecting families with regulated providers who have undergone appropriate background checks.

“If they go to social media or to the internet to try to find a provider, they may not find a provider who is actually regulated,” Hilarie said. “If there are reviews … it’s subjective to whatever that personal experience has been. When you’re searching for care, it’s a highly personal choice, and there’s so many programs out there.”

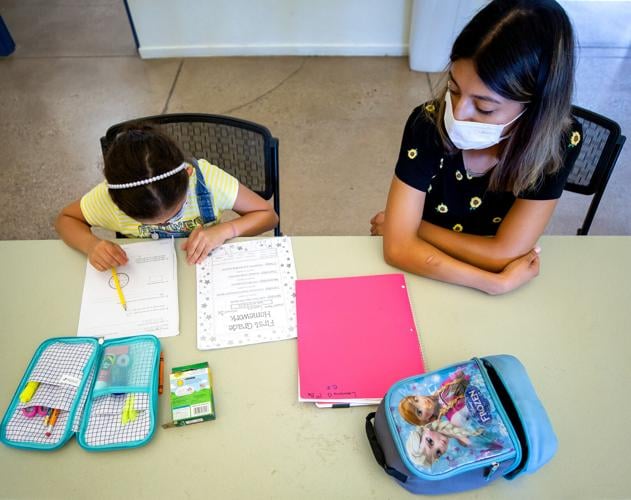

A preschooler draws during a class at Desert Spring Children’s Center in Tucson. The cost of high-quality child care for toddlers is out of reach for most Arizonans.

AZCCRR gives families tools that allow them to evaluate and do the research to make the most informed decision for their child, and they’ll have a list of options to choose from based on their needs.

“You can’t get that anywhere else,” Hilarie said. “The biggest piece of education we provide is education on financial assistance options, because it’s very confusing and overwhelming.”

With multiple government programs, the option to use state and federal tax credits and other types of financial assistance, it can be challenging for families to figure out the option that best fits their needs and qualifications, Hilarie said.

Stepping up to fill in gaps

Recognizing the need for affordable, quality child care, some employers, schools and agencies have stepped up to help fill the void.

At Pima Community College, counselors and others refer students to the state’s 211 phone line, the referral service for social service agencies, according to spokeswoman Libby Howell.

“We are working on plans to place a child care facility on the Desert Vista campus, hopefully sometime by next spring,” Howell said. The early learning center will part of the state’s Head Start program, and be available to students, staff and community members. Priority will go to students, then staff and if there are still spots available, the public.

El Rio Healthcare refers new hires, employees and, if needed, patients to the Arizona Child Care Resource and Referral website, “since child care needs are so different with everyone,” said marketing coordinator Nathan Holloway.

Such outreach efforts intensified during the COVID-19 pandemic, when schools were shut down, offering online learning only.

Last year, El Rio created a COVID child care assistance fund to help employees who were working and needed support with unexpected child care expenses, Holloway said.

The fund paid a one-time reimbursement to employees with children ages 5 and older who were enrolled in school.

El Rio didn’t stop there while their employees were working on overdrive to help the community. The emergency child care project, which ran from March through July 2020, helped provide care for 63 children belonging to 42 of its employees.

With $52,000 spent by El Rio on YMCA day camps for kids ages 5-12 and nearly $10,000 in payments to private child care providers for kids younger than 5, it was a heavier lift than expected.

“We came in at $20,000 over the amount covered by our grant funding,” Holloway said.

The city used $1.25 million of federal pandemic relief funds for child care. Thanks to a group of activists and nonprofits, it was able to distribute scholarships to many families — especially frontline workers — at a time when day care centers were shutting down.

The Economic Policy Institute’s Gould said there have been a lot of conversations about women having to take the brunt of the recession, due to the caregiving needs.

“This was not just about kids in child care, this was also affecting kindergarten kids and the parents and first- and second-graders,” Gould said. “If you have to go to work in person, you can’t leave these kids alone.”

Nonprofits have long stepped in to fill the gap and assist clients struggling with child care issues, even before the pandemic.

“YWCA believes that child care is a huge barrier for women,” said Imelda Esquer, director of the YWCA of Southern Arizona’s Latina Leadership Institute, who has heard firsthand from many how difficult it is to complete their educational goals due to the child care barrier.

Esquer said one woman told her that having no access to child care for her two kids was a huge obstacle to her attending her GED classes. Other women struggling to complete their GED course work have asked if they could bring their children along to classes, due to the high costs of both child care and transportation.

While the Latina Leadership Institute doesn’t have a formal child care referral process just yet, Esquer says they do support women bringing their kids with them.

“We have a program called YKids which makes a tremendous difference and positive impact on the community we serve,” Esquer said.

YKids has two components: homework help and gardening, exercising and crafts.

“We encourage the Ykids and mothers to share what they learned while being at the same center,” Esquer said, adding that the institute is working to implement the two-generation, or 2Gen, approach to its programming. 2Gen builds family well-being by simultaneously working with children and the adults in their lives together.

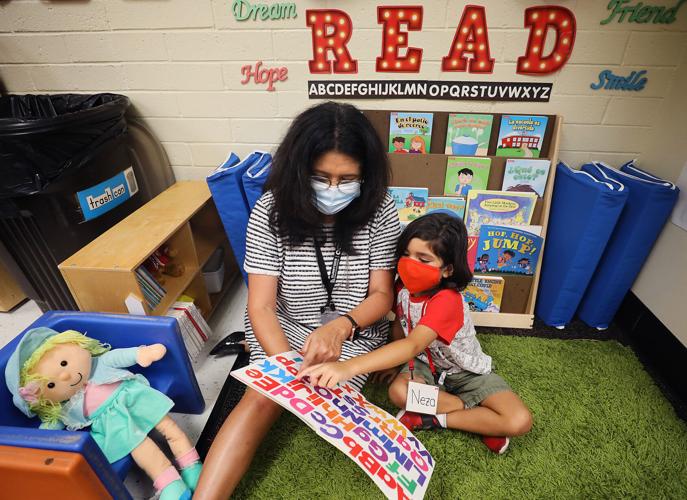

Leonora Oquendo, 6, works on her homework while Suzeth Rodriguez, a volunteer, keeps an eye on Oquendo during an after school program at Las Abuelitas, 440 E. 26th St. Las Abuelitas, a community run by the Primavera Foundation, has a dozen affordable apartments as well as a free after school program.

The path to a sustainable future

Local leaders are well aware that it’s going to take more than referral lines and nonprofits stepping up to solve the problem. They point toward the state and federal government to take charge.

The path to a sustainable future is two-pronged, and includes the need to expand capacity of the “high-quality system” and providers that accept DES, as well as the need to improve coordination and outreach, Pima County Administrator Chuck Huckelberry said in an email.

“Over the next three to five years, there is significant opportunity to improve the preschool and child care system locally and in Arizona, due to the vast sums of federal pandemic relief funding for the industry, increased awareness of the problem, and the county’s new program,” Huckelberry said.

The Pima Early Education Program Scholarships (PEEPS) program focusing on families with incomes at or under 200% of the federal poverty level aims to serve about 1,200 children this year, roughly 20% of the program’s target.

Huckelberry estimated that there are roughly 9,000 Pima County children who fall within the aforementioned group and are not attending a high-quality preschool through some type of subsidy.

Thanks to the Trump and Biden administrations, through the CARES Act, Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act and the American Rescue Plan Act, Arizona secured about $1.2 billion in federal relief funding to help child care providers survive the pandemic. Last fall the city of Tucson allocated $500,000 in CARES Act funding for child care scholarships, administered through Catholic Community Services of Southern Arizona.

However, the greatest challenge to increasing access to high-quality preschool and child care is that there simply aren’t enough classes and providers that are rated or accredited as “high quality,” Huckelberry said.

“Over the next three to five years, there is significant opportunity to improve the preschool and child care system locally and in Arizona, due to the vast sums of federal pandemic relief funding for the industry, increased awareness of the problem, and the county’s new program,” said Pima County Administrator Chuck Huckelberry.

“There are more funds available for subsidies and scholarships than can be spent because of this bottleneck,” Huckelberry said, pointing toward two paths to quality.

The first is through First Things First’s Quality First improvement program and rating system for preschools and child care centers.

Quality early learning centers include caregivers and teachers who know how to work with infants, toddlers and preschoolers; learning environments that encourage creativity and imaginative play; hands-on activities that stimulate and encourage brain connections in kids; positive relationships that provide young kids with the individual attention they need and caregivers who provide regular feedback to parents on their child’s development.

For the past several years, there was a long wait list to get into Quality First, along with limited funding. But thanks to some pandemic-related windfalls, temporary funding could help alleviate some of the issues.

DES will be using federal pandemic recovery funding to move 800 providers statewide off the waitlist and into Quality First over the next few years, and First Things First is also making sponsorship options available for providers to move into the program.

One-time pandemic funding will also help deal with the issue of accreditation.

“Some providers are nationally accredited, but unlike Quality First, there isn’t public funding to support accreditation,” Huckelberry said. “It is a cost paid by the provider and providers serving largely low income families may not be able to afford the cost or see much of a return on the investment.”

DES pays a higher child care subsidy reimbursement rate for some national accreditations, and this year, those will surpass the First Things First scholarship rates for nationally accredited and Quality First providers.

“(This makes) it more attractive to providers to be nationally accredited and/or in Quality First, and to accept children with DES child care subsidies,” Huckelberry said.

While the state is left to figure out how to make the one-time funding increases sustainable, United Way has been hard at work on the Accelerate Quality development program, which was developed to complement the county’s PEEPS program.

As part of the program, preschools with a 2-star rating from Quality First can receive financial and other assistance to increase quality and prepare them to score at a 3-star level, which is considered high quality.

Accelerate Quality was funded by donations from Tucson Medical Center, El Rio, Southern Arizona Leadership Council, Community Foundation of Southern Arizona, other philanthropic donors and individual donations.

“Preschools not yet in Quality First can receive assistance in completing the application and preparing for the rating assessment, and those already in Quality First with a 3-star or greater rating who have space to add additional classes can receive financial or other assistance in getting those additional classes operational,” Huckelberry said.

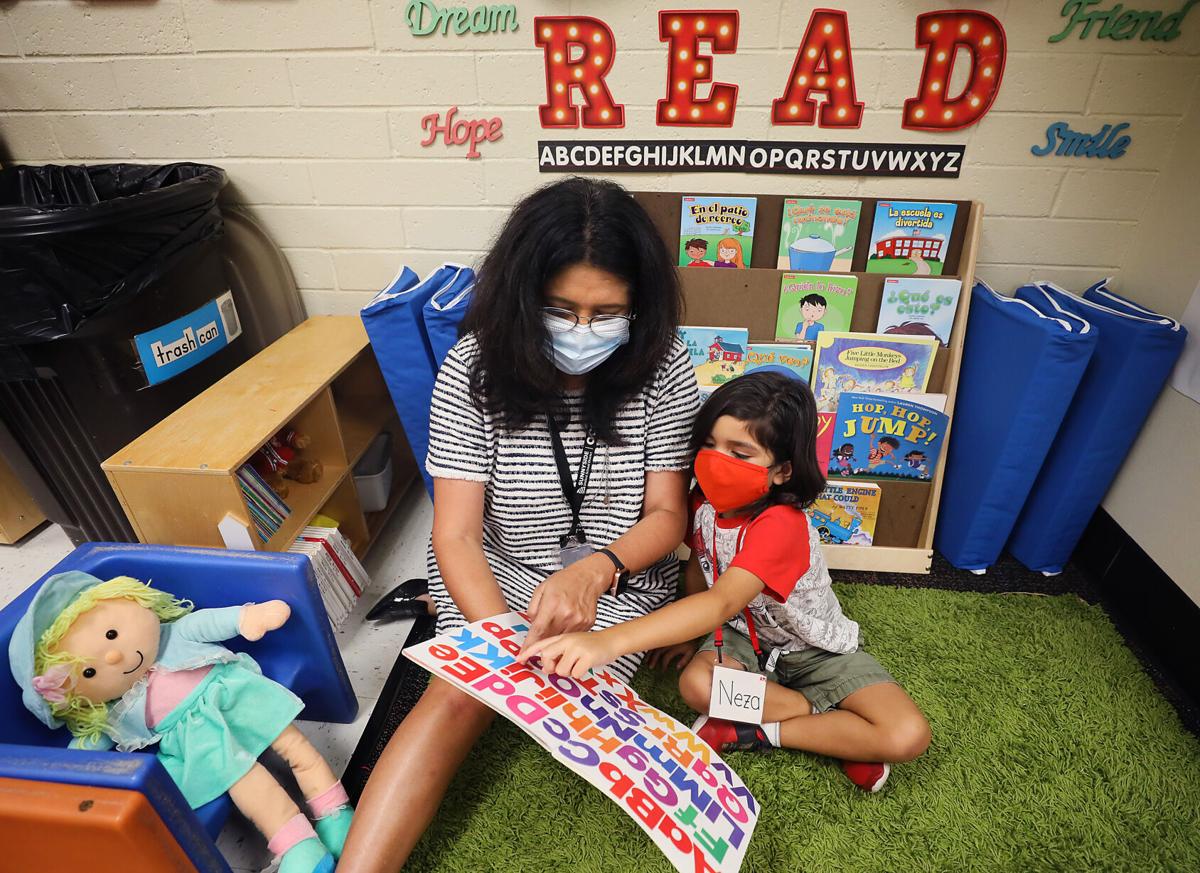

Elizabeth Ridout, an infant teacher at Herencia Guadalupana Lab School, prepares a bottle. The average annual cost of infant care in Arizona is $10,948.

However, the major roadblock toward expansion in Pima County comes in the form of a lack of qualified teachers and child care professionals, according to Huckelberry.

“Currently TUSD and Amphi’s new PEEPS classes are on hold because they have been unable to hire teachers,” Huckelberry said. “This was an issue pre-pandemic and is even more of an issue now — nationally and locally.”

With no short-term solution to the teaching shortage in sight, Huckelberry said there are lots of discussions underway.

Huckelberry pointed toward ease of access as another issue, which comes down to the need to improve coordination and outreach.

“It needs to be easier for families to access the variety of financial aid available,” Huckelberry said.

First Things First, DES and Head Start all have different eligibility criteria and applications. While DES and First Things First are discussing coordinating their income eligibility checks, Huckelberry said more work needs to be done.

“The county has an opportunity now to advocate for system-level changes via our regularly scheduled meetings with FTF, DES and Head Start, as well as our role as a funder and contractor,” Huckelberry said.

“Long term, the state needs to increase funding for this purpose as they spend almost no state funding on this,” Huckelberry said. “The county, cities and towns, and other local funding partners now have a vested interest in seeing this system improve and in working together to advocate for increased state funding.”

Changing the trajectory

Mayor Romero said the road to accessible, affordable, high-quality child care needs to start at the federal level.

A $3.5 trillion proposal under discussion in Congress could potentially be a lifejacket for women in the workforce in more ways than one, Romero told the Star.

Earlier this month, Senate Democrats voted to pass a budget resolution that would direct committees to draft a bill that would invest substantial funding into child care, education, health care, paid leave and climate initiatives.

Tucson Mayor Regina Romero said the road to accessible, affordable, high-quality child care needs to start at the federal level.

The resolution would make child care more accessible, create universal pre-K and more.

“Universal pre-k for 3- and 4-year-olds and child care for low-income working families could be a game-changer for the country,” Romero said. “That could be the solution to the issue that we see throughout the country in terms of affordable child care.”

It won’t be happening just yet though, as the Senate’s vote is the first step in the process. The House of Representatives also needs to approve a budget resolution before Congress can craft and pass final legislation, which could take months.

Romero said that while affordability is a serious problem, there’s also the issue of child care deserts in low-income areas, where high-quality child care is harder to find.

Nearly half of all Arizonans live in a child care desert, regions with an under-supply of licensed child care, according to a 2018 report from the Center for American Progress. Nationally, Latino and Hispanic families have an even tougher time finding child care near their homes: Almost 60% of that demographic lives in a child care desert.

Many Latino parents also rely on extended family or friends for child care, said Pima County Supervisor Adelita Grijalva. Grijalva said both she and her mother relied heavily on family members while raising their babies; Grijalva attributes her Spanish-speaking abilities to growing up so close to her nana.

While intergenerational connections are important, those who rely solely on family members miss out on the long-term developmental benefits of highly trained educators at high-quality preschools, she said.

“A lot of times those parents and grandparents don’t have the skills, necessarily, to help with early reading and early literacy,” she said. “Those things, and the social skills, are things that our abuelitas and nanas can’t provide.”

Studies have shown that children that start their education earlier are more likely to be successful throughout their educational careers, which helps families and communities move forward.

“I’m proud of what we’re doing, I’m pretty sure the investment Pima County is making is 100% the right move,” Romero said. “But we can’t do it alone. We need the federal government and state government to step up and help create high-quality, affordable child care. We need the federal government to see this as an investment in our future.”

The Economic Policy Institute’s Gould agreed, saying public investment of this magnitude is great to be done at the federal level, where those kinds of resources are available.

“It’s a long-term investment that’s not just good for Tucson or Pima County or the state, but for our country,” Romero said. “It could change trajectory of our country.”