Tucson school districts are spending millions to get kids back on track after a year of remote learning, but not all of them know how they’re going to pay for the remediation strategies that are needed.

Arizona’s K-12 allocation from the third COVID-19 stimulus package — the American Rescue Plan, passed by Congress in March — is $2.5 billion, with about $645.5 million to address learning loss.

Pima County’s nine major school districts have already received $158 million from the first two rounds of stimulus funding, and the Arizona Department of Education expects to calculate allocations from the latest round in the next few weeks, with those allocations likely totaling more than twice what school districts received in the second round of funding.

But even as school districts estimate what they’ll get from the third round of stimulus funding, some say they don’t have enough for the remediation efforts students need because the way the funding was distributed leaves huge disparities in how much different districts received per student.

From the second stimulus package, TUSD received about $1,800 per student while Tanque Verde only received about $86 per student.

Each district’s allocation, decided through a federal government formula, was largely based on the number of students they have who qualify for free and reduced lunch — a measure of poverty. Therefore, Tanque Verde, Catalina Foothills and Vail school districts all received less than $150 per student while TUSD and Sunnyside each received more than $1,500 per student.

School districts with more low-income children often had more expenses during the pandemic for things like providing online devices and hotspots for remote learning due to a lack of access to technology. Low-income children were also less likely to have parents available to help with schoolwork during the school day while parents were working.

Despite those disparities, most Pima County school districts saw an increase in F’s, even though some districts and individual teachers made their grading practices more lenient.

School districts don’t yet have data on how a student’s economic reality may have affected their education, but it’s clear that across all Tucson districts, students experienced some form of learning loss during a year marked by complete or partial distance learning — necessitating the need to spend money on catching kids up to grade-level standards.

The Amphi School District distributed its one millionth meal since beginning meal distribution on March of last year, on Jan. 6, 2021.

The district has been serving a week's worth of meals including breakfast, lunch, dinners and snack every Wednesday as a part of the extended Summer Feeding Program.

Currently, the service is expected to continue until June 30, 2021. (Josh Galemore / Arizona Daily Star)

Like most school districts when the pandemic hit, the number of failing grades in the Vail School District shot up. And although Vail created ways for students to get their grades up, that doesn’t necessarily indicate they have mastered the skills the way they would have in a normal year.

Vail, which has about 13,600 students, is working on a plan to combat student learning loss, but right now that plan is just a wish list, says district spokeswoman Darcy Mentone.

“The problem is that at the moment we can’t fund it,” she said. “We’re going to have to dip into our reserves just to pay for a free summer school this summer.”

Another funding disparity that surfaced is between traditional district schools and charters. A funding adjustment for small schools meant that some charter school companies got funding allocations for individual schools and received more per student than some school districts.

For example, Basis charter schools throughout the state received nearly $6.9 million combined, which breaks down to about $434 per student and is more than the per-student allocations for Catalina Foothills, Marana, Sahuarita, Tanque Verde and Vail school districts.

The Arizona Department of Education recognizes that all schools have relief and recovery needs, said spokesman Richie Taylor.

“We have strongly advocated for the governor’s office and state Legislature to provide full funding for distance learning and enrollment stability in the state budget and will continue to do so,” he said.

Most school districts lost funding because of the fact that Arizona funds schools based on kids physically in seats, and paid schools 5% less for remote learners although the cost of educating those children did not decrease.

Between all three rounds of stimulus bills, which includes an estimation for the third round, Vail will barely have enough to cover the 5% percent they lost because of remote learning, Mentone says.

BRIDGING THE GAP

Most Tucson school districts will offer additional summer school courses, and many districts say the new courses and programs will involve credit recovery and learning activities that address learning gaps the districts are finding.

Amphitheater, for example, created a program that started in March for high school students in danger of losing credits or falling behind for their graduation dates, with free Wednesday evening and Saturday classes, as well as a new summer program meant to help students acclimate to school academically, socially and emotionally, with credit recovery courses in the upper grades.

Aside from the districts that got the lowest amount of stimulus funding, most say they will fund remediation efforts from the three stimulus packages.

Like Vail, Tanque Verde, which has about 2,000 students, is also concerned about its ability to fund all the remediation strategies it would like to implement.

“The inequitable distribution of ESSER funds has resulted in an inadequate funding amount, which definitely will not cover the anticipated additional remediation costs,” says spokeswoman Claire Place, referring to the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund — the title of the stimulus portion that goes to K-12 schools.

Interventions the Tanque Verde district would like to implement include smaller class sizes, additional adults in classrooms, longer or additional school days, more reading and math specialists at schools, summer school, after-school tutoring, academic opportunities during fall or spring breaks, credit recovery, formative assessment to determine areas of learning gaps and reteaching standards from the prior grade level.

One problem with not having enough money to fund multiple interventions is that no single intervention or strategy alone is enough to overcome the education gaps students are now facing, the district wrote in a letter that will be sent to the state Legislature.

“Research does show that when schools implement systematic ongoing supports that respond to students’ needs, the impact on learning will be more than three times a normal year’s growth,” the letter says.

In Catalina Foothills, the funds received from the first two stimulus packages did not cover what the school had to spend on COVID-19 mitigations, says spokeswoman Julie Farbarik.

“We don’t begrudge any other district’s allocation, but it would have been helpful at least to have been held harmless for these unanticipated expenses,” she said. “Instead, our local taxpayer-funded maintenance and operations budget will pay the difference. This is the same source that funds teacher salaries and benefits, curriculum materials, instructional supplies, etc. As a result, budget planning for 2021-2022 that is underway is incredibly challenging.”

She says the district will need to use some of the new stimulus funding to cover those costs, reducing the money available for academic intervention planning.

“It would have been really helpful to receive stimulus funds based on student enrollment and not based on the socioeconomic status of the families in the school,” she said.

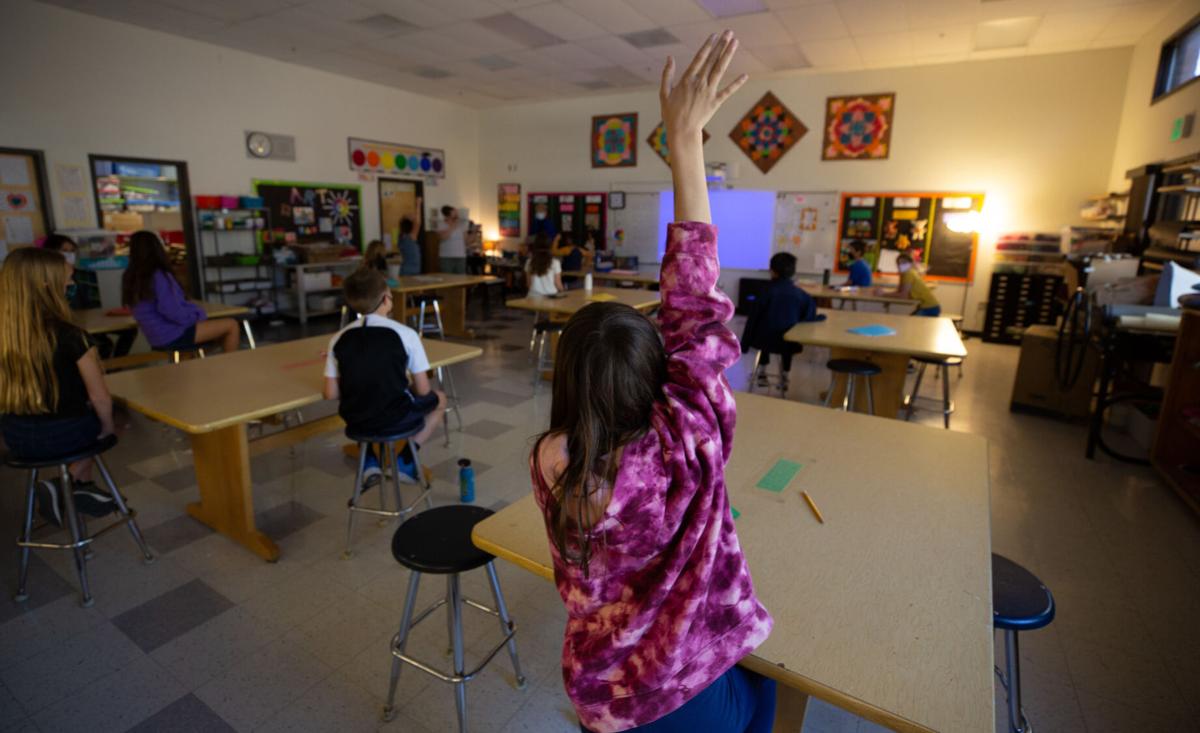

Mari Katherine Scruggs, a teacher at Rincon Vista Middle School, creates the best-possible learning experience for her students as she navigates both remote and in-person instruction during the coronavirus pandemic of 2020-2021. Video by: Mamta Popat / Arizona Daily Star

Photos: TUSD begins in-person full-time instruction

TUSD in-person instruction

Updated

Julian Salomon, second grader, listens to his teacher Ingrid Reyes during class at Holladay Magnet Elementary School, 1110 E. 33rd St., in Tucson, Ariz. on March 23, 2021.

TUSD in-person instruction

Updated

Grace Beltran, co-teacher and curriculums service provider, teaches a group of students about spacing by having students hold out their arms before classes started at Holladay Magnet Elementary School, 1110 E. 33rd St., in Tucson, Ariz. on March 23, 2021.

TUSD in-person instruction

Updated

Roman Leon, fourth grader, completes his bellwork during the beginning of class at Holladay Magnet Elementary School, 1110 E. 33rd St., in Tucson, Ariz. on March 23, 2021.

TUSD in-person instruction

Updated

A student walks past a hand sanitizer station while heading outside to eat breakfast before classes start at Holladay Magnet Elementary School, 1110 E. 33rd St., in Tucson, Ariz. on March 23, 2021.

TUSD in-person instruction

Updated

Julian Salomon, left, second grader, listens to his teacher Ingrid Reyes during class at Holladay Magnet Elementary School, 1110 E. 33rd St., in Tucson, Ariz. on March 23, 2021.

TUSD in-person instruction

Updated

Kindergarten students work behind plexiglass during class at Holladay Magnet Elementary School, 1110 E. 33rd St., in Tucson, Ariz. on March 23, 2021.

TUSD in-person instruction

Updated

Kinder-gardeners jump on one leg while playing "Simon Says" outside during a break from class at Holladay Magnet Elementary School, 1110 E. 33rd St., in Tucson, Ariz. on March 23, 2021.

TUSD in-person instruction

Updated

Trevor Salago, magnet site coordinator, gives hand sanitizer to kinder-gardener Alexander Morales-Bermudez at Holladay Magnet Elementary School, 1110 E. 33rd St., in Tucson, Ariz. on March 23, 2021.

TUSD in-person instruction

Updated

Maria Doniz, janitor, sanitizes a students desk while the class plays outside at Holladay Magnet Elementary School, 1110 E. 33rd St., in Tucson, Ariz. on March 23, 2021.

TUSD in-person instruction

Updated

A drawing talking about mask wearing made by Grace Beltran, co-teacher and curriculums service provider, is taped to a wall at Holladay Magnet Elementary School, 1110 E. 33rd St., in Tucson, Ariz. on March 23, 2021.