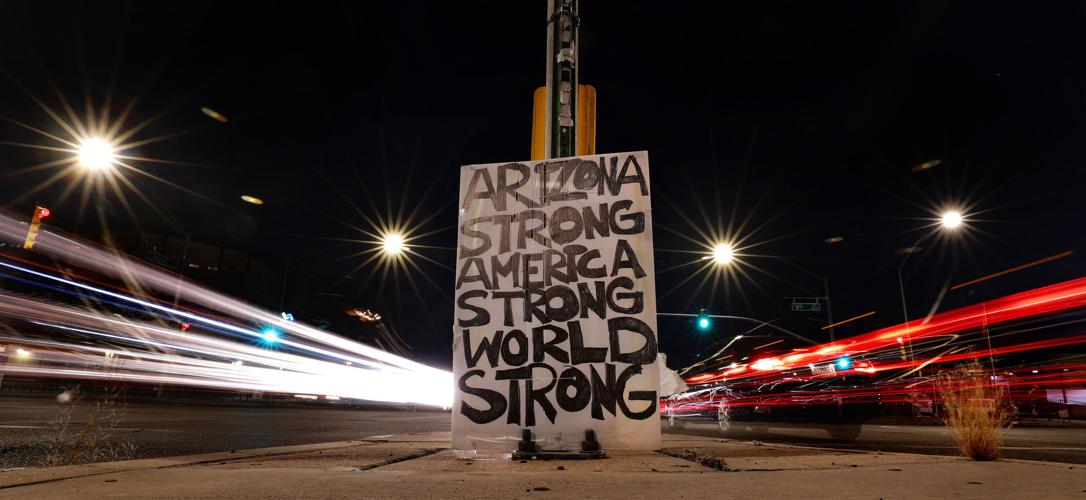

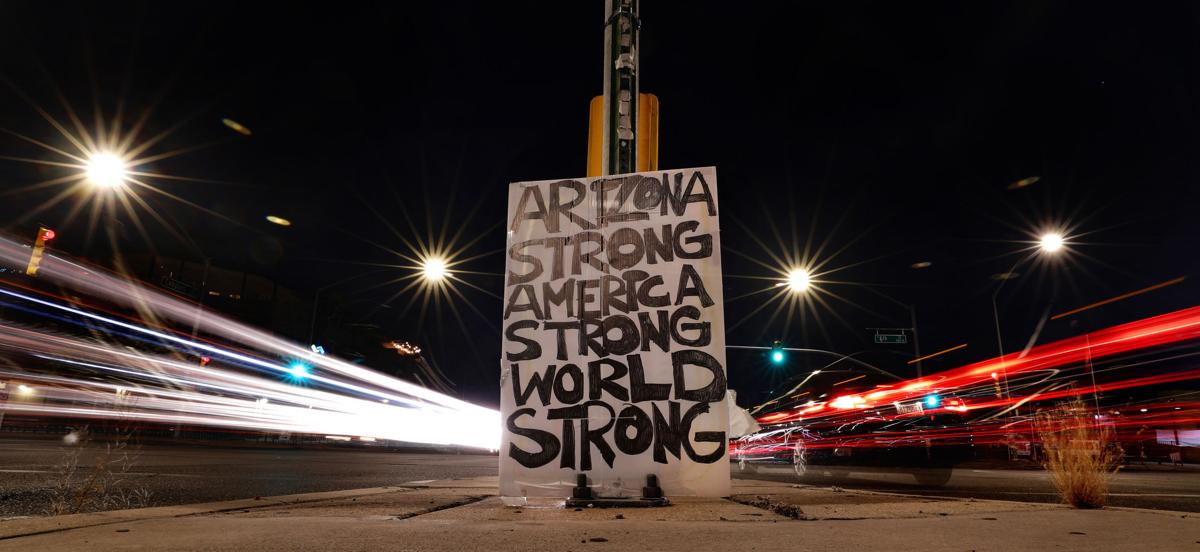

One year ago this week, the coronavirus pandemic rode into Tucson on a wave of disruptions.

Schools were closed. Workers were laid off or sent home. Major events were canceled, including the Fourth Avenue Street Fair, the Tucson Festival of Books and postseason basketball for the Wildcats and everyone else.

Then on St. Patrick’s Day, just hours before the start of one of the busiest nights of the year for local bars, city officials closed down the rest of it. Every bar, restaurant, gym, museum, movie theater and other entertainment venue in Tucson was ordered to shut its doors by 8 p.m.

Some of them still haven’t reopened. Some of them never will.

The city’s March 17 lockdown order came exactly one week after Pima County confirmed its first case of COVID-19. Less than two weeks after that, the virus claimed its first local victim — a 54-year-old wife and mother who worked as a receptionist at an east-side pediatric clinic.

Since then, more than 110,000 Pima County residents have contracted coronavirus. At least 2,270 of them died.

And it isn’t over yet. There are vaccine rollouts and falling infection rates to give us hope, but we’re still smack in the middle of this thing.

It’s already been a year. It’s only been a year. The before seems impossibly long ago. The after feels tantalizingly close.

Here is a look at where we started and where we are now:

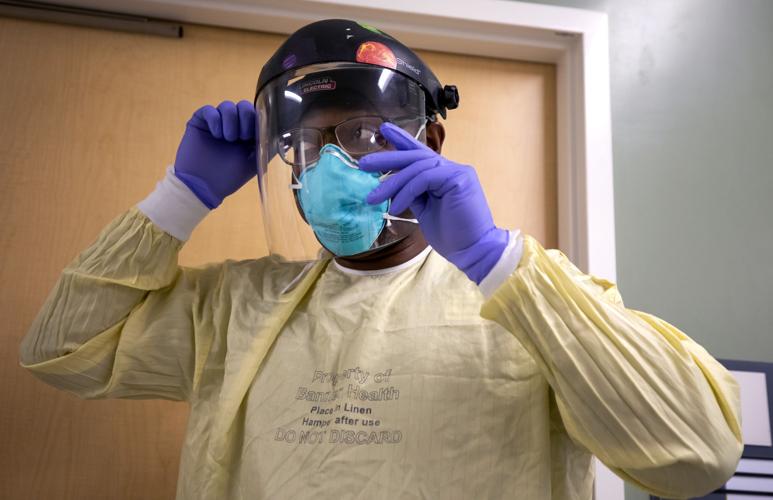

Dr. Christian Bime, medical director of Banner-University Medical Center’s intensive care unit, said, “The patients just kept coming and coming and coming nonstop.” By mid-April, the ICU reached a breaking point and requested more help.

Families mourn loved ones taken too soon

When Jaclyn Gallegos saw her father for the last time, she was saying goodbye through the small screen of her cell phone.

Less than 24 hours later in his Tucson nursing home, 71-year-old Carlos Gallegos took his last breaths at 4:15 a.m. on July 14.

“I miss him every day. I think about him every day. I cry for him. I dream about him,” Jaclyn said. “And that’s never going to go away.”

Carlos Gallegos was one of many nursing home residents whose lives were cut short by COVID-19 over the last year. While coronavirus cases in long-term-care facilities have been on the decline in recent weeks, the virus has devastated nursing homes across the nation, spreading rapidly among residents and staff members early on in the pandemic.

As of March 1, Pima County had recorded more than 2,800 cases in long-term-care facilities, resulting in 447 hospitalizations and 446 deaths. While these facilities only make up 3% of the county’s total confirmed cases, they also make up nearly 20% of total deaths.

“What kills me the most is that we could not be there by his side to say goodbye,” Jaclyn said. “When you’re a little girl, you look at your parents and you think they’re never going to die and you dread that day. But when that day came, we couldn’t even be there to hold his hand.”

Carlos was admitted to Casas Adobes Post Acute Rehabilitation Center in 2019. When the pandemic started, Jaclyn, her mom and siblings were immediately concerned about what this could mean for him. In addition to living with dementia, Carlos survived several strokes, two heart attacks and quadruple-bypass surgery.

“He always recovered from everything. That man was very strong and resilient,” Jaclyn said. “And even with dementia, he still had a very sharp mind.”

Carlos graduated from Tucson High School in the late 1960s and was immediately drafted to join the Army, where he earned a Bronze Star for fighting in the Vietnam War. He was an avid businessman and a Tejano music enthusiast who loved to dance.

“We’re all very strong because of him,” Jaclyn said. “He was the leader of our family.”

Just a few weeks after Arizona lifted its stay-at-home order, Jaclyn received a call from the nursing home saying that her dad had spiked a fever.

“My heart just dropped,” she said. “And the next few days, his health just deteriorated. It was really hard for him to breathe and he was nonresponsive most of the time.”

Just a few days later, a test showed Carlos was positive for COVID-19. By Monday, July 13, Jaclyn knew it was time to say goodbye and asked the nurse if they could FaceTime her so she could see him.

“He perked up when he heard my voice,” she said. “I just told him how much I loved him and that we were sorry we couldn’t be there and that it was OK to let go. That was the last time I saw him alive. Because of his dementia, I don’t think he realized there was a pandemic going on in the outside world. And I think he was wondering, ‘Why isn’t my family here with me?’”

Jaclyn said her family has struggled to adjust to life without him. She was recently diagnosed with stage 2 breast cancer, and she said she takes her father’s ashes with her to chemotherapy so she can “feel dad’s strength” around her. As the pandemic continues, she said the loss of her dad hasn’t gotten any easier.

“My mom and I both work in health care, so we understand the logistics and how everything works. We’re not pointing fingers or blaming anybody, but it’s just hard,” she said. “Looking back and seeing that we have vaccines now is just heartbreaking. It could have saved his life. He was only 71. He had a lot of longevity left in him.”

— Jasmine Demers

Jaclyn Gallegos, left, with her father, Carlos Gallegos; her brother, Anthony Gallegos; and her mother, Teresa Gallegos. Carlos passed away from COVID-19 on July 14. Jaclyn says of Carlos: “I miss him every day. I think about him every day.”

Carlos Gallegos, one of many nursing home residents to die of COVID-19, graduated from Tucson High School in the late 1960s. His daughter, Jaclyn, says she takes his ashes with her to chemotherapy so she can “feel dad’s strength.”

Fatigue, frustration for medical workers

Front-line health-care workers will always remember this past year, even if they would rather forget it.

“The virus came out of nowhere and caught everyone by surprise,” said Dr. Christian Bime, medical director for the intensive care unit at Banner-University Medical Center. “There were a lot of unknowns initially. We did not know at first how this virus spread.”

So in addition to the stress inherent to working in a busy ICU, medical staffers had to worry about getting sick themselves and possibly infecting their loved ones at home.

Bime said his worst day on the job came about a month after Pima County recorded its first coronavirus cases.

“Early on in the pandemic, we struggled with how to protect ourselves and care for patients with COVID-19,” he said.

The hospital initially tried to limit staffing in the ICU to avoid exposing too many caregivers to the virus. For weeks at a time, Bime was one of just two doctors assigned to see COVID patients on the day shift, “but the patients just kept coming and coming and coming nonstop,” he said.

By mid-April, they had reached the breaking point. Bime told the hospital’s administration that they needed more help.

Over the past 12 months, Bime said, he has intubated roughly 100 times more patients than at any other point in his 20-year career. He has also seen a lot more people die.

The onslaught has taken a toll on people in his line of work.

“There is a high rate of burnout among front-line professionals,” he said. “People are tired. Work becomes a burden instead of a joy. We’ve used up all our energy.”

The pressure only grew late last year, when the number of cases shot up again and Arizona briefly became “the COVID-19 capital of the world,” Bime said.

This time, though, the surge came with an added emotion: frustration.

By October, he said, it was abundantly clear what we all needed to do to slow the spread of the virus, but some people still refused to take even basic precautions. A few of those stubborn individuals ended up in the ICU with tubes down their throats to help them breathe, but Bime said just as many of his patients were innocent victims of other people’s carelessness.

“We see people die. We don’t have the luxury of calling it a hoax,” he said.

That’s one of the key lessons to be learned from the pandemic: “Disinformation can be very, very dangerous,” Bime said. “If we are honest with ourselves and seek the truth, then we will always be in a better place.”

So what was Bime’s best day on the job since the pandemic started? That one’s easy: Dec. 17, the day he got vaccinated.

“Because there was hope finally,” he said.

If you had told Bime a year ago that there would be three different vaccines already in widespread distribution by March of 2021, he wouldn’t have believed you.

“It’s a tremendous victory for science,” he said.

— Henry Brean

Sunnyside High School’s Angel Medina Garcia, 17, has helped arrange some online contests and other remote activities to try to engage students during the pandemic.

Learning to cope with what they’ve lost

Schools closed a year ago. The announcement came on a Sunday, as most Tucson students headed into spring break.

“We were told that we were going to get an extra week of spring break, which was exciting,” said Angel Medina Garcia, a senior at Sunnyside High. “And then another two weeks became a month and then the whole year was canceled.”

Teenagers have missed out on quinceañeras and sweet-16s, football games, proms and graduations. And while many would rather be in school, whether they think it’s worth the risk to their families or themselves often depends on their situation at home or what part of town they live in.

The neighborhoods within the Sunnyside School District have had some of the highest COVID case numbers in Tucson, along with Tucson Unified, which has kept classrooms closed for a year.

Minority students and those from low-income families are more likely to live in multigenerational households, with grandparents or adults who have health conditions that put them at higher risk.

Medina Garcia moved out of his grandmother’s house and in with his aunt and cousins when the pandemic began for fear of putting his nana at risk.

He began going to school two days a week when Sunnyside opened for limited in-person learning in October. As COVID-19 numbers rose during the second spike, many students in the district began staying home again. But Medina Garcia stuck with it.

When the district went back to remote learning over the holidays, he noticed more students kept their cameras off during class. They interacted less with one another, and teachers struggled to keep them engaged.

Halfway through the school year, thousands of Tucson students were failing classes while dealing with remote learning and the many challenges of the pandemic. Sunnyside and most other Tucson school districts plan on spending millions in COVID-19 relief funding on remediation efforts to help get kids back on track.

But nothing can replace the pivotal year teenagers lost.

School was Jordan Good’s social outlet. The Ironwood Ridge senior worked on the student newspaper, and that was her escape.

“I lost the sense of community at my school,” she said. “I can’t get it back because it’s going to end.”

Ironwood Ridge High School senior Jordan Good, 18, has found coping mechanisms to deal with the virus. She swims at a local pool, walks in nature and explores new places in her car.

With that loss came a sense of loneliness that wasn’t there before. Good has coping mechanisms. She swims at a local pool, walks in nature and explores new places in her car.

Other kids have struggled to find their own ways to cope. Referrals to mental health agencies that treat children and teens have gone up over the last year, and Pima County saw a 67% increase in suicides among children ages 12 to 17 in 2020.

Medina Garcia stays pretty positive with the support of his friends and family, and he tries to share that positivity with others. As Sunnyside’s student body president, a post he splits with his best friend Paola Mendivil, he’s helped arrange some online contests and other remote activities to try to engage students.

But Medina Garcia’s true inspiration lies ahead in college and adulthood. He turns 18 next month, and he’s excited to see what the future holds for him.

“I’m hopeful that this pandemic will end soon, hopefully sooner than expected,” he said. “I’m just excited to go back to some normalcy,” whatever that looks like now.

— Danyelle Khmara

Doug Couchman, 54, was one of Pima County’s earliest confirmed cases of COVID-19. He went through about a week of being “pretty damned sick” before recovering.

Early diagnosis and a year without fear

Doug Couchman caught one of Pima County’s earliest confirmed cases of COVID-19. He was also one of the first local residents to go public about it.

The 54-year-old semiprofessional bridge player believes he was infected during a weeklong tournament at the Tucson Expo Center. The event drew more than 800 players, including some from Colorado Springs, where a woman in her 80s died from the virus after playing in a bridge tourney there.

Couchman said he chose to speak out a year ago to warn his fellow bridge players and push back against the belief at the time that the virus was not spreading in Tucson.

When his symptoms came on, he checked himself into a motel to keep from exposing his family.

Tests were hard to come by at the time, so his physician brother swabbed his nose and sent it off to a lab. The result came back positive on March 16. Three days later, his story was featured in the Star.

Couchman ended up spending 17 days at the motel, including about a week of being “pretty damned sick.”

“I had my route to the hospital mapped out, but I never went,” he said.

Not long after he went public, Couchman said he began getting calls multiple times a day from commercial companies that wanted to buy his blood for research purposes. Some of those offers felt “slimy” to him, he said, so he ended up donating his plasma to the Red Cross about a dozen times and providing samples to researchers at the University of Arizona. He said some of his blood was used in the development of a campus coronavirus test.

“As it turned out, I was really good at making antibodies, so I gave them every chance I could,” Couchman said.

All told, it took about six weeks for his breathing to return to normal. He feels mostly fine now, though he wonders about some long-term effects.

He’s not complaining, though. He knows he is much better off than a lot of people, including the more than half a million Americans who have died from COVID-19.

In some ways, contracting it as early as he did was a blessing. Couchman considered himself immune after that, so he spent much of the past year free from the sort of anxiety most people have been feeling. He could do the grocery shopping for his family and even travel a bit without worrying about what might happen — though he still wore a mask and washed his hands, just in case.

“The world has sucked, but my world has not sucked as much as it has for almost everyone I know, because I had nothing to be afraid of,” Couchman said.

As for that difficult decision a year ago to make his private life public, he said he feels vindicated by everything that has happened since then.

“Live bridge is essentially played nowhere, and it won’t be until our members are vaccinated,” Couchman said. “I wasn’t initially sure (about speaking out), but I was right. It sure felt like the normal human thing to do, once I got over the fear.”

— Henry Brean

Juan Almanza, owner of El Rustico, opened his place 24 hours after restaurants were ordered to close their dining rooms last March. It survived the lockdown and is thriving.

A risky move Or a genius move?

People thought Juan Almanza was crazy for opening a new restaurant 24 hours after all food establishments were ordered to close their dining rooms last March.

And for the first few months, he couldn’t disagree with them.

Business at El Rustico Mexican restaurant started slow — a couple hundred bucks a day on the weekends, less than that on weekdays. He had made that much in an hour or two with his taco cart at the Tohono O’odham swap meet, where he was a regular vendor every weekend for five years before COVID-19 shut it down last March.

He joined other Tucson restaurateurs in online marketing campaigns. He did his own social media outreach, advertising his signature queso birria tacos.

On Cinco de Mayo, the tide turned. He made enough on that day to pay the month’s rent. And for the first time since opening on March 21, 2020, he and his wife, the only employees at the time, felt comfortable taking a paycheck from the restaurant at 2281 N. Oracle Road.

From that busy day in May through last week, Almanza’s little taco shop has been hopping. From June through December, he estimates he sold 50,000 tacos.

Many of the state’s restaurants did not have Almanza’s luck. The Arizona Restaurant Association, which represents 2,500 of the state’s 9,000 restaurants, estimates 10% to 12% of them closed during the pandemic. That’s about 1,000 restaurants, including Tucson’s iconic Café Poca Cosa and Janos Wilder’s Downtown Kitchen + Cocktails, Rigo’s on South Fourth Avenue, El Indio on the south side and Athens on 4th, a Greek restaurant that had been on North Fourth Avenue for nearly 30 years.

“Some have had prior challenges and COVID was the last straw,” said Steve Chucri, the restaurant association’s president and CEO. “I think a lot of them would have been able to (succeed), but COVID-19 treats its friends and enemies the same.”

Chucri said that at the height of the pandemic last spring and summer, 80% of the state’s restaurant workers were unemployed. That number has improved as COVID-19 restrictions have been lifted, including Gov. Doug Ducey’s move last week to increase restaurant capacities. Chucri estimates the unemployment rate at restaurants is down to about 20%, and most of those displaced workers are involved in catering, which has yet to rebound.

“We are not out of the woods, but as more people get vaccinated, we certainly are seeing a light at the end of the tunnel,” said Michael Guymon, vice president of the Tucson Metro Chamber of Commerce, who oversees the chamber’s Tucson Restaurant Advisory Council.

The council, working with local operators including Ray Flores of Si Charro restaurants, helped businesses secure state, city and county grants to help pay employees and keep the lights on.

“Because of the work that we’ve done and the programs we have been able to introduce, we have helped a lot of restaurants get through this period,” said Guymon.

Last week the council rolled out Keep Tucson Cooking, a new public service initiative that promotes local restaurants and educates diners about safety protocols.

— Cathalena E. Burch

Roadrunner Bicycles’ Elliot DuMont says he can’t keep bikes in stock and that COVID-19 has “truly been industry-changing.”

Peddling pedals in a pandemic

A lot of local businesses have struggled or even failed during the pandemic. Others have never been busier.

Elliot DuMont owns Roadrunner Bicycles, a shop on Broadway near Wilmot Road that has been in his family for 16 years. He said the past 12 months have been crazy.

With gyms locked down and people stuck at home, many have turned to cycling for exercise and to get outside with their kids. The sudden surge in demand — both in bike-friendly Tucson and across the globe — has overwhelmed manufacturers, leaving retailers with lots of customers and little to sell.

“It’s truly been industry-changing,” DuMont said. “The supply chain just stopped.”

Much of the demand is for entry- and midlevel bikes, which range in price from about $450 to as much as $1,200.

“A lot of people are getting into cycling for the first time,” DuMont said, “and Tucson is a pretty great place to ride a bike.”

In a few days, DuMont will be getting his largest shipment since the pandemic began: 11 bicycles, some of them already pre-sold. He expects the rest to be gone in a week or two. Roadrunner’s waiting list for new bikes is two pages long.

The repair business is booming, too, as people haul their old bicycles out of the garage and bring them in for tuneups. DuMont said his repair shop is booked solid for the next month, and getting replacement parts — once available for overnight shipment — poses an additional challenge. “Some stuff I can’t get until 2022,” he said.

Before the pandemic, Roadrunner also operated a healthy bike rental operation. But as demand for new bicycles rose and uncertainty about possible lockdowns grew, DuMont decided to sell off his rental fleet as a hedge against what could be a rough road ahead.

Now he’s looking to get back into the rental game, maybe by this fall, as life slowly returns to normal.

All he needs are a couple dozen extra bicycles.

— Henry Brean

New mom found help in hard year

Carolina Flores was newly single, and newly a mother, when COVID-19 started upending lives.

Flores had no idea how much the pandemic would complicate her situation, or how one decision she made back in March 2020 would help her and her son, Leonardo, make it through a tremendously difficult year.

Hardship first arrived before the pandemic, when her relationship with Leonardo’s father ended a month before the baby was born on Feb. 25.

A nurse at Tucson Medical Center recognized Flores could use some extra support, so she urged the young mother to sign up for a program called Healthy Families Arizona.

In simplest terms, Healthy Families links new parents or caregivers with a caseworker who supports the family and provides education about child development.

Flores hesitated, but after a hard week home alone with a newborn — and with the pandemic beginning to dominate the news — Flores called for help.

That decision saved her, she said.

“If not for them, I don’t know what would have happened. It’s been such a blessing. So many things happened this last year, and they were there.”

Usually, Healthy Families caseworkers visit with parents in person, but in the past year they’ve had to rely mostly on phone calls.

For Flores, 29, the calls helped her understand Leonardo’s behavior and patterns and taught her things she could do to foster his development.

Flores said she also received advice about jobs. She needed income, but regular work was hard to come by. With support from her caseworker, Maria Maldonado, Flores was able to figure out how to work at home while also caring for Leonardo.

“She was really understanding and gave me tips to help me be there for my baby through those difficult hours,” said Flores, whose job in online video surveillance started at 2 a.m.

Although Healthy Families Arizona caseworker Maria Maldonado can’t meet with parents in person because of COVID-19, she has still provided crucial help in other ways.

Steady work was a blessing, but by the fall it meant giving up her Medicaid benefits and food stamps. Maldonado helped her figure out her bills, and where to get extra food when she needed it.

“They got me hooked up to a bunch of resources where they could help me,” Flores said.

Maldonado was also there to help her cope with grief: Flores lost both of her grandmothers to COVID-19.

It was in mid-December when Flores’ maternal grandmother died from the virus, forcing her mother — who helps by watching the baby so Flores can sleep — to leave for Mexico to settle her own mother’s affairs.

The timing was horrible. Flores and the baby both woke up with fevers a few days later.

“We’d seen his dad two days before we started feeling really bad,” she said. She called Leonardo’s father and learned he was also very sick.

Flores and the baby spent Christmas alone, sick with COVID-19.

“Maria dropped food on our porch for Christmas dinner,” Flores said. “She dropped off diapers. She saved us.”

Now, as the one-year anniversary of COVID-19 arrives and vaccinations are increasing, Flores said she is starting to feel a bit more optimistic about the future. But she’s still sticking close to home with Leonardo, comforted by the fact Maldonado is just a phone call away.

“Healthy Families,” she said, “is the best thing that could have happened to me this year.”

— Patty Machelor

Santa Rita’s Candice Pocase went 5-0 and finished third in her weight class at the state high school wrestling championships. “I’m really wanting to work harder this year,” she said. “I’m ready to move on from COVID, ready for that to pass over.”

Wrestling with the future

Candice Pocase’s spring competition season didn’t turn out the way she’d planned.

The Santa Rita High School multisport athlete qualified for state in the pole vault her freshman and sophomore years, and she expected to do the same as a junior.

But the pandemic had other plans, and Pocase’s season ended early. So did the seasons of thousands of other Southern Arizona high school athletes.

The bad news didn’t stop there: A few months later, Pocase received a late concussion diagnosis from a wrestling match the previous winter.

She stopped training altogether for the next several months.

By July, however, she was able to start working out for her senior cross country season. However, with state- and county-mandated safety protocols, that training looked quite a bit different.

“Wearing a mask all the time, and sometimes having to run in a mask … it didn’t prevent me from practicing, but it made it a bit tougher,” Pocase said.

She also had a new coach for the first time in three years and competitions were hard to come by, but Pocase still nearly made it to the state meet.

Once the Arizona Interscholastic Association gave the all-clear for winter sports to proceed, Pocase turned her attention to wrestling. But practicing for that sport proved even more of a challenge than cross country.

“Some days, we couldn’t be close and had to stay separate,” Pocase said. “But it didn’t really hinder it so much to the point that it was the worst thing ever.”

Just like with cross country, she also had to get used to a new wrestling coach. But Richard Sanchez wasn’t new to Santa Rita, Pocase or the sport, having signed on as the school’s football coach and athletic director two years earlier after a stellar career as a coach and administrator at Sunnyside.

Pocase went 5-0 on the season and traveled to Gilbert for the state championships last weekend. She finished third in the 126-pound weight class, attributing much of her success to Sanchez, who she called a “phenomenal coach.”

“The best part of this year was that it’s given me the chance to work with him,” Pocase said. “(Sanchez) has been helping me out through everything.”

That “everything” includes narrowing down her plans for college. Pocase initially wasn’t sure which of her many athletic endeavors to pursue; she’s also been a member of Santa Rita’s football and volleyball teams.

With Sanchez’s help, Pocase has decided to focus on wrestling.

“It’s a big decision,” Pocase said of which college she’d like to attend. “Coach Sanchez is helping me identify good schools and good opportunities.”

Sanchez said Santa Rita has been lucky to have Pocase, calling her a great student-athlete.

“Candice is very positive, coachable and really fun to be around. She’s pretty strong, she’s quick and she’s a quick learner,” Sanchez said. “I think she has a lot of potential (in college wrestling.) Whoever gets her will definitely be able to mold her into the type of wrestler that they want.”

But before she heads off to college, Pocase hopes to make up what she lost out on last year, and return to state for one more run at pole-vault champion.

“I’m really wanting to work harder this year,” she said. “I’m ready to move on from COVID, ready for that to pass over. But I’m not ready for school to pass over. I’m going to miss school.”

— Caitlin Schmidt

For months, Caryn Stedman stepped out of her home at Houghton Road and Catalina Highway and rang a bell at 8 p.m. as a way to connect during the early lockdown. She is now decorating her home for each holiday “to cheer up the neighborhood.”

Ringing stopped, but neighborly spirit lasts

One year ago this week, northeast-side resident Caryn Stedman started ringing bells each night in front of her house at Houghton Road and Catalina Highway as a way to connect during the lockdown with the people living around her.

The gesture soon spread, carried to other parts of town by the Nextdoor app, a social networking platform for neighborhoods.

Within days, hundreds of people had joined the 8 p.m. ritual, including a family with a train whistle on Bear Canyon Road and someone with a ship’s bell near Broadway and Houghton.

Stedman said she kept the bells ringing well into June, but the whole thing died out over the summer, when online comments on the Nextdoor app and elsewhere filled with nasty political rhetoric about the pandemic being a hoax. Stedman didn’t feel very connected to her community after that.

Then something wonderful happened around the holidays: Her neighborhood lit up with Christmas lights, more than she ever remembers seeing there before. Houses that had never decorated were suddenly aglow.

Stedman couldn’t help herself. “I went completely nuts with the Christmas lights,” she said.

She even invited some of her neighbors over for a socially distanced champagne toast when she threw the switch on her display for the first time on the Saturday after Thanksgiving.

She has decorated the front of her house for every holiday since — first Valentine’s Day, now St. Patrick’s Day, and next up, Easter.

“I’m mainly doing it to cheer up the neighborhood,” she said.

Of course, Stedman and her neighbors have something else to feel warm and hopeful about these days. As it turns out, the shot in the arm has been a real shot in the arm.

“As more of my neighbors are getting vaccinated, we’re starting to make plans to get together,” Stedman said.

Hopefully by then, she said, any distancing will be entirely optional.

— Henry Brean