If you’re going to make it as an amphibian in the desert, you have to get hopping when an opportunity presents itself.

Monsoon season in Tucson is also mating season for a variety of native frogs and toads.

They seem to appear out of nowhere after the first big thunderstorm, filling the night with their distinctive calls and, occasionally, ending up in people’s swimming pools.

Truly Nolen exterminator Jeremy Christopherson said he gets one or two calls each summer from a customer with a small plague of frogs in and around their pool.

There isn’t much he can do about it, though. “It’s out of my scope of practice, let’s put it that way,” Christopherson said.

University of Arizona research scientist Phil Rosen said there are about a half-dozen different species local residents might see from now until late August — all of them adapted to survive through long dry spells and breed right away when things occasionally get wet.

They’re mostly active at night, but if conditions are right “they’ll be out in the daytime doing it — and I literally mean doing it,” Rosen said.

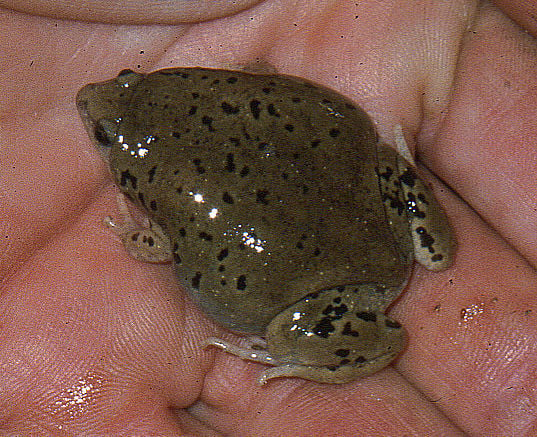

The most common of them is the Couch’s spadefoot, a blotchy, 3-inch, green and yellow toad that’s technically not a toad at all.

According to the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum, the spadefoot lies dormant underground during hot, dry periods and is drawn out of hiding not by monsoon moisture but by the low-frequency sounds and vibrations of rainfall and thunder.

No one reproduces faster, Rosen said. Their eggs have been known to hatch in just 15 hours, and they can complete the transformation from “tadpole to hopper” in as little as a week — assuming the puddle they are deposited in lasts that long.

In addition to the all-important moisture, amphibians are drawn out this time of year by another monsoon mainstay: flying ants. After a storm, Rosen said, swarms of the insects will emerge, touching off a feeding frenzy by frogs and toads.

Construction crews started laying the foundation for a 30-foot tall border wall across the San Pedro River in Cochise County. As of July 8, they already built about a half-mile of wall to the east of the river.

Other local species include the red spotted toad, which is especially common in the Catalina Foothills; the Mexican spadefoot; the deafeningly loud Great Plains toad; the aptly named Western narrow-mouthed toad; and the brightly colored Sonoran green toad, which Rosen described as a “beautiful jewel of the desert.”

You also might see the tiny canyon treefrog, if you follow intermittent streams into the surrounding mountains.

Then there’s the Sonoran toad, that grayish green, wart-covered monster of “hallucinogenic fame,” Rosen said. Also known as a Colorado River toad, the 7-inch-long croaker produces a defensive toxin that’s powerful enough to kill a full-grown dog.

Depending on where you live, any of these species could potentially wind up in your swimming pool, Rosen said.

For some, it’s a one-way trip. They jump in but can’t get out, eventually exhausting themselves and drowning or succumbing to pool chemicals.

So what can pool owners do to keep the frogs and toads out this time of year? “Get rid of the water,” Christopherson said with a laugh.

Rosen suggests fencing pools with aluminum flashing or another material that is partially buried in the ground, so toads and frogs can’t squeeze under it or climb over it.

If you do find one in your pool, simply scoop it out and place it in a cool, shady spot, Rosen said.

There are also several ramps and floating platforms on the market — including one called a FrogLog — designed to help amphibians and other animals escape from pools.

Just don’t ask Christopherson to come take care of the problem for you. Though the unwritten motto of his profession is “if it bugs you, it’s a pest,” he draws the line at killing toads, frogs and lizards — either on purpose or indirectly with the overuse of pesticides that collect in the environment.

As far as he’s concerned, insect-eating reptiles and amphibians are the allies of bug guys like him. “They’re helping us. They’re making our job easier,” he said.

So this monsoon season, spare a thought for our desert-adapted amphibians as they wriggle from the ground in search of love and a little lunch.

Their numbers appear to be declining in and around Tucson, and we’re all likely to miss them when they’re gone, Rosen said. “If we run the planet down to cars and cockroaches, it’s going to be pretty damned boring.”

Photos: A look at what life was like in Tucson in the 1960s

New shopping center

Updated

Shoppers check out the new shopping center at South 12th Avenue and West Ajo Way on July 5, 1968. The center featured a Safeway grocery store and a Walgreens drug store.

'High Chaparral' filming

Updated

Actor Cameron Mitchell, center on horseback, gallops into a scene on the set of the television show "High Chaparral" at Old Tucson in May, 1968.

Hippie Wedding

Updated

Some guests find a nice quiet place on the floor where they could have a smoke while with some pets as Roxanne Carnes and Clyde Pitts celebrate their wedding at a home on May 3, 1968. The nuptial took place at 819 N. First Avenue crowded with well-wishers, many of whom were barefoot and with some of the men shirtless. Beer flowed in paper cups both during and after the service. There was also a presence of marijuana on the premises which was duly noted by the invited journalists.

UA Rush Week

Updated

Delta Gamma pledges Adrienne Niblett of Birmingham, Ala., and Laurie Reed of Tucson (backs to camera), get hugs from Delta Gamma members Mimi Muse of Fullerton, Calif., and Mary Jo Stewart of Tucson during Rush Week at the University of Arizona in Sept. 1968.

Joseph Bonanno, Sr.

Updated

Peter Notaro, left, believed to be a bodyguard, moves to help Joe Bonanno as the Mafia leader arrives in Tucson in 1968 to visit his home in Catalina Vista.

El Conquistador Hotel

Updated

Historic bathroom fixtures, windows and doors salvaged from the hotel before demolition sit in the lobby of El Conquistador Hotel in March, 1968.

Grant Road Lumber fire

Updated

Waitresses from a nearby restaurant serve coffer to Tucson Fire commanders during a fire at Grant Road Lumber on May 14, 1968.

Grant Road Lumber fire

Updated

Neighbors and restaurant/bar patrons watch a fire at Grant Road Lumber on May 14, 1968.

Magic Carpet Slide

Updated

Magic Carpet Slide on Alvernon Way south of 22nd Street in September, 1968.

Sahuaro High School

Updated

Students explore the library during open house at Sahuaro High School, Tucson, on Aug. 16, 1968.

Southern Pacific bridge demolition

Updated

Two Southern Pacific F7 locomotives pulling freight are the first to cross over the newly completed bridge over the Cienega Wash in March, 1968. The original 1903 span bridge was replaced after a freight collided with it.

Lenny's Texaco

Updated

The grand opening at Lenny's Texaco gas station at East Broadway Boulevard and North Swan Road offered free gifts to their customers in March 1968.

Tucson International Airport

Updated

Tucson International Airport passenger gates in September, 1968.

Transit strikes in Tucson

Updated

Striking members of Local 1167, Amalgamated Transit Workers, stop a bus exiting the Tucson Transit Corp. bus yard on Plumer Ave. in Tucson on June 5, 1968.

Tucson nightclubs in 1968

Updated

The Tally Ho Tavern and Cocktails at 546 N. Stone Ave., in Tucson, in August, 1968.

Tucson nightclubs in 1968

Updated

The bar at The Cedars, 3501 E. Speedway in Tucson in August, 1968.

Tucson nightclubs in 1968

Updated

H. Aram Guiezyan plays the oud at Sanders, Piece of Mind, on 6th Street in Tucson in August, 1968.

Iceland fun

Updated

Boys play hockey at Iceland, 5915 E. Speedway Blvd.

Midtown Market

Updated

The Midtown Market and Liquor Store was at 258 S Stone Ave and West McCormick Street. It is now the parking lot of the Tucson Police Department's main building. The photo was taken on July 12, 1968.

Tucson Army Surplus Store

Updated

Tucson Army Surplus Store which was located north of Broadway on the southwest corner of Mesilla and Meyer. Constructed in 1891, was originally the H. Menager Dry Goods, Clothing and Hardware store. A partner of Henry Meneger was Sabino Otero who had ranches outside of Tucson. Over the years various businesses occupied the site. July 12, 1968. Photo by

Greyhound Bus Station

Updated

Greyhound Bus Station, area buildings. July 12, 1968.

Protests

Updated

Anti-war demonstrators march their way to City Hall while policemen ensure there are no incidents. January 15, 1968.

Poverty series

Updated

Just off South Park Avenue, a young girl reaches into the refrigerator in her home on April 3, 1968. The photo was part of a poverty package that ran in print.

Robert Kennedy

Updated

During Robert F. Kennedy's speech at the University of Arizona, people for and against crowd outside the auditorium with signs.

Robert Kennedy 2

Updated

Robert F. Kennedy is greeted by many admirers at the Tucson International Airport during his campaign. He is to speak at the University of Arizona. March 29, 1968.

Robert Kennedy support

Updated

Robert F. Kennedy speaks to admirers and non-admirers at the University of Arizona. March 29, 1968.