Benjamin Wilder first came to Tumamoc Hill to battle buffelgrass during a period he jokingly refers to as the “walker wars.”

The two issues were emblematic of the challenge researchers faced as they tried to add to more than 100 years of research at a preserve surrounded by development and invaded by buffelgrass and other nonnative plants.

The hill, a companion of “A” Mountain just west of downtown, is sliced by pipelines, trails and a road that fills each day with walkers and runners.

Wilder returned to Tumamoc Hill this month as its interim director. The buffelgrass he helped beat back has returned and up to 1,500 people still walk or run to the summit each day along a paved road that gains 750-feet in elevation in 1½ miles.

Wilder intends to renew the fight against buffelgrass, but has no intention of reviving the “walker wars,” during which university officials attempted to limit or ban use of the popular exercise site. He would rather educate the walkers about the preserve and enlist them, possibly as formal members of an organization dedicated to preserving the natural setting.

Wilder said Tumamoc, an 860-acre preserve, where the Carnegie Institution established the Desert Laboratory in 1903, is the place where he came of age as a scientist.

He was an undergraduate at the University of Arizona when he was hired in 2004 by Julio Betancourt, a researcher with the U.S. Geological Survey, to help create a model for controlling buffelgrass — a grass imported for erosion control that now threatens the region’s ecology.

It was his first real job, said Wilder, if you don’t count washing dishes in his father’s restaurant. He is the son of Tucson restaurateurs Janos and Rebecca Wilder.

He said he learned community organizing in his job and immersed himself in the spirit of the hill where many of his heroes had worked — Paul Martin, Ray Turner and Janice Bowers, among many others. He heard the tales of research trips taken by the “desert rats” — trips that combined experts in a variety of disciplines on either side of the U.S.-Mexico border.

He teamed up with botanist Richard Felger, who helped him pursue his intense curiosity about the region where the Sonoran Desert meets the sea. His exploration of the islands in the Gulf of California led to a number of research papers and a book, “Plant Life of a Desert Archipelago,” that he co-authored with Felger.

Wilder continued his research in the Gulf of California as he pursued his doctorate at the University of California-Riverside under Exequiel Ezcurra, a noted naturalist in the field of coastal deserts. While there, he helped create a group called Next Generation Sonoran Desert Researchers.

Wilder said he wanted to find out if that community of “desert rat” researchers still existed, and whether people were interested in revitalizing their interdisciplinary and cross-cultural ties.

“The answer was a resounding ‘yes’ and we hit on a nerve,” he said. The group now numbers 400, evenly split between Mexican and U.S. researchers. Wilder is director of the group.

Wilder returned to Tucson and the University of Arizona last year to join the Consortium for Arizona and Mexico Arid Environments as a research scientist.

He said when Joaquin Ruiz, UA vice president for innovation, asked him to take on the role of interim director, he said yes immediately, but told Ruiz he wouldn’t be just a caretaker.

“I don’t necessarily want to view this as an interim role. I want to start working toward my vision from the beginning. This is really a dream come true. My roots are here and I am absolutely connected to this place.”

Ruiz said in an email that Wilder’s combination of interests make him “the absolutely best candidate for the job. His role in other important international organizations such as the binational consortium in the study of semi-arid environments and the next-generation scientists of the desert fit perfectly with the mission of the Hill,” Ruiz said.

Betancourt, his first boss at Tumamoc, said Wilder has the passion and skills to revitalize the place and make it again a center of Sonoran Desert studies.

The Desert Laboratory was that center for much of its history, Betancourt said in a phone call from Washington, D.C., where he is a senior scientist with USGS.

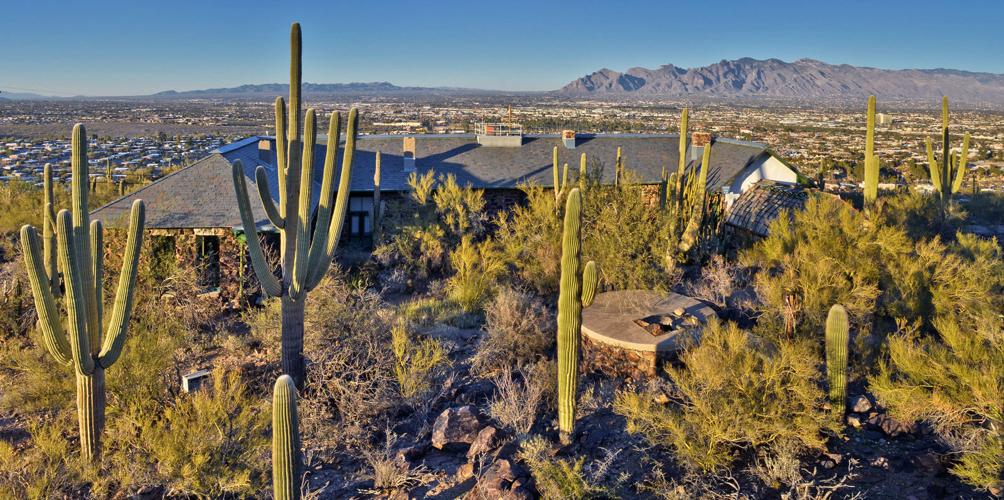

“When it was overlooking a city of 10,000, people would gravitate toward the hill because there were people at the forefront of desert ecology, like Forrest Shreve and W.B. McDougall. Now you’re overlooking a metropolis of 1 million people. Some of the issues have changed, but a young guy like Ben, he’s got vision and fire in the belly and a love for the desert and a conservationist spirit. Frankly, I’m very excited to see what he does with it.”

“The real challenge, like it is with everything at the university, is funding,” Betancourt said. He said the university has invested little in Tumamoc Hill in the 56 years it has owned it.

“I don’t think the university can afford this neglect much longer. It’s a formal ecological reserve on the National Historic Register. It has this long, long history and it’s really visible. It could be so many different things.”

Michael Rosenzweig, who stepped down as director after announcing his retirement from the university at the end of the current academic year, said he is proud of the work he’s done to bring public attention to the history and ecology of the preserve.

Rosenzweig, a UA professor who founded the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, introduced “science cafes” and snagged grants to line the road with interpretive signs about the wildlife on the hill.

Walkers now stop and read the signs along the road, said Clark Reddin, operations director. Reddin said most of the walkers are protective of the hill and its century-old research plots.

They are our “best asset,” Reddin said.

Rosenzweig said the big challenge in his eight years as director was “to get the UA higher administration to understand what it was they were in charge of and what is was they could do and get them interested in the place.”

Its employees — a director, operations manager, program coordinator and field research director — all have other duties and are at Tumamoc part-time, he said.

“When the hill was bought in 1960, it went from having a budget to not having a budget and that’s still true,” said Rosenzweig.

The historic stone buildings at the foot of the hill and midway up are in need of repair, Rosenzweig said. “Any human structure will decay and fall down. Those structures are decaying without any real repair and attention,” he said.

Elliott Cheu, UA associate dean of science, said limited resources are a fact of life at all of the UA’s outreach centers. “While resources certainly limit the kinds of things we can do, being fairly entrepreneurial in the process can help. I agree, in the ideal world, if you could double or triple budgets, you could do amazing things, but that’s not the world we live in.”

Cheu noted that Wilder is already planning a phone app that will interpret the ecology of the hill for walkers and is planning to write a grant to get that done. Wilder said he is also planning to turn a building at the bottom of the hill, known as the “boathouse,” into an interpretive center.

Wilder said he wants to answer the essential question for the hill’s future: “What does it mean to be an ecological preserve in an urban matrix addressing arid-land questions?”

Wilder wants to see Tumamoc become a focus for the investigation and promulgation of knowledge about our regional environment and the threats to it.

“What society demands from a scientist now is to leave the comforts of academia,” he said.

“Climate change, mega-droughts, increased periods of less rainfall and higher temperatures are going to put great strains on our resources, on the function of society and the ecology of the region. We have a lot of answers to these questions ... but they stay within our own academic community in jargon-filled papers behind pay walls,” he said.

“I want to make this a center of activity once again that’s addressing those questions.”