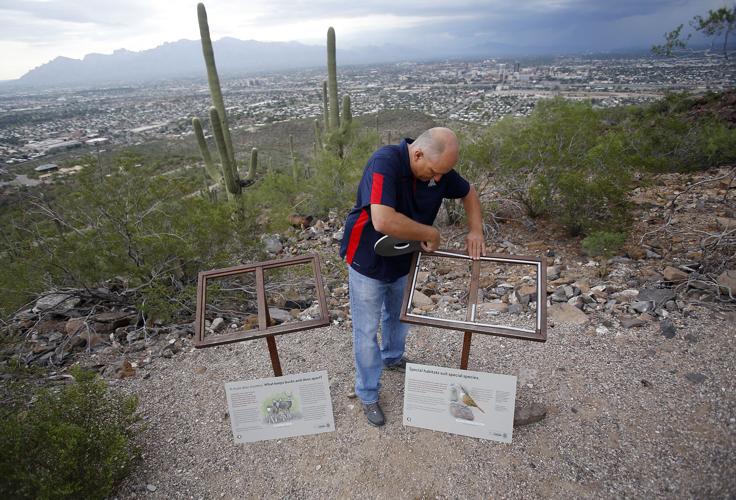

Clark Reddin, director of UA operations on Tumamoc Hill, installs a sign describing some of the animals that call the area home.

Michael Rosenzweig wants to turn Tumamoc Hill’s platoons of hikers into an army of advocates for preservation of the biological and archaeological preserve.

Signs recently installed along the popular westside walking trail are part of that process, said Rosenzweig, director of Tumamoc: People and Habitats.

Each of the signs, which are placed at intervals along the 1.5-mile paved road, has a sketch of one of the preserve’s inhabitants, along with a brief lesson in desert ecology.

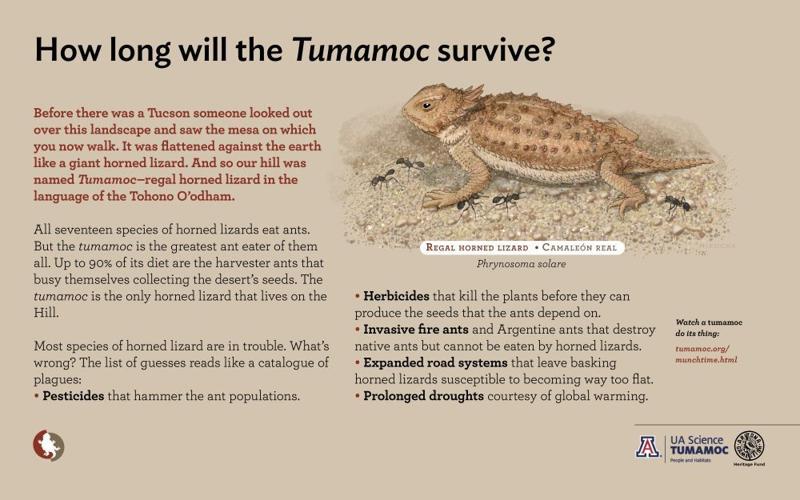

The “Tumamoc” itself, the regal horned lizard that the outline of the flattened peak is said to resemble, is used to educate walkers about several phenomena that threaten its existence.

The horned lizard eats the ants that feed on the seeds of desert plants in the Sonoran Desert. Ant populations are threatened by pesticides and the plants they eat are threatened by herbicides, the sign notes. Invasive ant species can drive out the native ones and the lizard is additionally threatened by expanding road systems and prolonged droughts, courtesy of global warming.

Those interactions between the human environment and the natural one are a big reason for the the preserve’s existence. It was established in 1903 by the Carnegie Institution as the Desert Botanical Laboratory to study how plants survive in hot, semi-arid climates.

The 880-acre plot was not pristine. Its slopes had been grazed by cattle and horses. Its basaltic rock had been quarried for foundation stones for a growing Tucson.

The Carnegie scientists installed a barbed-wire fence and halted quarrying. It became, the Tumamoc website says, the world’s first ecological restoration project.

OWNERSHIP CHANGES

In 1940, the preserve’s ownership passed to the U.S. Forest Service, which allowed Marine Corps training and brick-making and also granted several utility leases.

In 1960, it was sold to the University of Arizona. It wasn’t immediately saved by that move, said Rosenzweig: The UA at first wanted to build dormitories on the site.

It didn’t, and today the only intrusions on the mountain are the communications towers and observatory on its summit and the now-historic stone buildings of the Carnegie scientists midway up the hill.

There is a steep, switchback road to the top, now closed to vehicular traffic but used by thousands of walkers and runners.

Signs announce the presence of the biological preserve, now run by the UA College of Science, and ask visitors to stay on the road and off the lush desert landscape where plots of desert species — typed, numbered and measured in 1905 — are studied to this day.

Until this week, though, there were no signs about the ecology of the place.

Even though it began its life as a botanical preserve, these first signs are about critters, not plants.

There is a practical reason for that, said Rosenzweig. Money to produce and install the signs came from a $35,000 Heritage Fund grant from the Arizona Game and Fish Department. It required animals on the signs.

It also insisted on editing the text, which, along with perusal by university committees, delayed installation of the signs for about a year.

The delays were frustrating but the editing was helpful, said Rosenzweig, especially on a sign about the mule deer that populate the place. “They had a spectacularly important influence on that — turns out I’d made a lot of mistakes,” he said.

PROMOTING ECOLOGY

Artwork on the signs was produced by Paul Mirocha, a scientific illustrator and graphic designer who has been “artist in residence” at Tumamoc for more than three years.

Mirocha does not actually reside on site — nobody does — but he uses an office there and runs occasional programs that bring artists, poets and writers to Tumamoc.

A book, “This Piece of Earth: Images and Words from Tumamoc Hill,” celebrates the place and raises money for its preservation.

Rosenzweig said he and Mirocha argued a bit over the number of words on each sign.

“I’m a professor. I work for the university, I’m supposed to be educating people.”

Mirocha said he sees the signs as suggestions to people to recognize the specialness of the place as they take their morning or evening exercise.

“We did have to rein Mike in on the writing,” Mirocha said. It’s not a university and these people didn’t sign up for a university lecture. We don’t think they’re going to stand there more than 15 seconds.

“To me, as a graphic designer, the goal is to get people looking out at the landscape and the plants and the animals.”

Mirocha said Rosenzweig did a good job of making his points about the ecology of the place without getting too technical. “People are often scared away by science. Mike did a pretty good job of writing these.

“The goal is get people engaged with this as a special place. I don’t think any other city has anything like it. It’s like a little glass bubble. Theoretically, if the Sonoran Desert disappeared, you could repopulate it with this ark.

And even though he still thinks the pieces “are a little bit long,” he thinks they will be read over time.

“People come here a lot,” he said.

The signs are designed to be inexpensively made and easily swapped. Mirocha said he envisions using them for temporary exhibits of art done on the mountain.

Clark Reddin, operations director on the hill, sited the signs where people naturally stop to catch a view or to catch their breath at the end of a steep slope. The 1.5-mile road gains 750 feet in altitude.

Reddin, who has worked on the hill nearly three years, said he also placed signs in areas where the animals have been sighted.

He said he was talking to a passing hiker who took about 10 steps from the mule deer sign and said, “There’s one.”

Reddin said response to the signs has been universally positive. Signs about the history and the science of the hill will be added over time, he said, with the “goal of creating a group of people who will be our stewards and help us monitor and maintain it.”

Rosenzweig said he’s attended public hearings about threats to the hill in the past where lots of people testified about the hill’s value as an exercise path. He said he hopes future such hearings will bring forth testimony about the site’s value as an ecological preserve.