The crews that spent more than a year hustling to build as much border wall as possible in Southern Arizona stopped working last week, at least in some places, after President Biden ordered a construction pause.

As a candidate, Biden promised “there will not be another foot” of border wall built during his administration. Hours after his inauguration on Wednesday, Biden directed federal officials to “pause work on each construction project on the southern border wall” as soon as possible and no later than seven days after his proclamation.

The Army Corps of Engineers directed contractors “not to install any additional physical barriers” along the border, according to a statement from the Corps on Thursday. Contractors were prohibited from doing any work except for what is “necessary to safely prepare each site for a suspension of work.”

While critics of the wall applauded Biden’s order and reported work stoppages from various parts of Arizona’s border with Mexico, their cheers came after the Trump administration built nearly all the 245 miles of wall planned for Arizona’s border with Mexico. And construction could start again after the Biden administration’s 60-day review of wall projects.

The wall consists of 30-foot-tall steel bollards filled with concrete. The bollards are 6 inches wide and separated from each other by 4 inches of space, which allows Border Patrol agents to see activity on the Mexico side of the border. The wall is topped with anti-climbing plates, and the foundation extends 6 to 10 feet underground to thwart tunneling.

“Not a serious policy solution”

In his order Wednesday, Biden said “building a massive wall that spans the entire southern border is not a serious policy solution. It is a waste of money that diverts attention from genuine threats to our homeland security.”

Former President Donald Trump told crowds at rallies that the wall was “like magic.” Border Patrol officials have said the wall will help slow down attempts to cross the border illegally and allow agents to cover more ground during their shifts. Agents have told the Star the roads that are part of the wall projects will help them quickly respond to incidents at the border.

“It stopped most older people and most younger kids. When they walk up and they see a 30-foot-high wall, it stops them,” Border Patrol Chief Rodney Scott told the Star last fall. “It doesn’t always stop the 22-year-old. It doesn’t always stop the super-agile. But you know what? Now it’s one (person),” instead of large groups crossing together.

Last week, Rep. Ann Kirkpatrick, a Democrat whose district includes part of the Arizona-Mexico border, said the wall “has always been a vanity project and campaign chant rather than an effective security infrastructure project.”

Since 2019, the Corps awarded $4.8 billion worth of contracts, paid for with Defense Department funds, to build 222 miles of wall in Arizona. Another 23 miles of wall projects in Arizona were funded by other means, including Congressional appropriations.

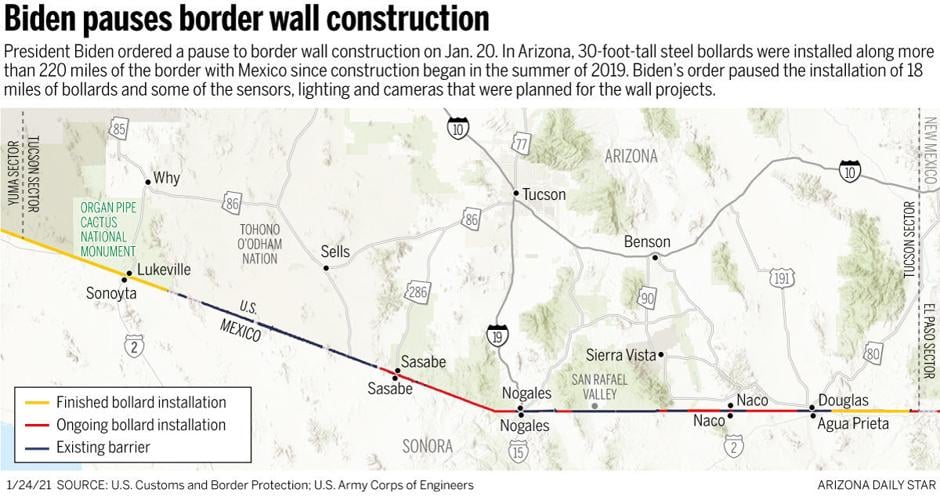

As of Jan. 15, contractors installed 226 miles of bollards on the Arizona border, according to Customs and Border Protection, leaving less than 20 miles still under construction. The Corps’ list of wall projects showed the installation of bollards was not complete as of early last week in areas near Sasabe, Nogales, Naco, the southeastern corner of Cochise County and a small area near Yuma.

Beyond the steel bollards, the installation of sensors, lights, cameras and roads, which make up what federal officials often call the “border wall system,” is not expected to be complete for any project in Arizona until the summer at the earliest, according to the Corps.

Shut down or wrap-up?

After Biden issued his proclamation, local residents and environmental advocates rushed to the border to ensure contractors were complying.

Migrants and human rights advocates are hopeful that U.S. immigration policies will change once construction of Donald Trump's border wall stops. On Wednesday President Joe Biden's first official act as President will be to sign an executive to immediately end the national emergency that Donald Trump declared on the border in February 2018 to divert billions of dollars from the Defense Department to wall construction.

Construction activity was shut down on Thursday, said Myles Traphagen, borderlands project coordinator for the Wildlands Network, who headed to a 4-mile wall project east of Nogales. No bollards had been installed yet in that project, he said.

John Kurc, a photographer who has spent months documenting the wall project in Guadalupe Canyon in the southeastern corner of Cochise County, particularly the blasting of rock at construction sites, said the last blast he saw was on Wednesday morning.

Laiken Jordahl, borderlands campaigner at the Tucson-based Center for Biological Diversity and longtime critic of the wall, posted a video on Friday of a wall project across the San Pedro River in Cochise County showing contractors had vacated the area.

Jordahl later posted a video showing activity at a wall construction site on the Coronado Memorial, a mountainous area a few miles west of the San Pedro River. Kurc said he saw “earthmovers all over the west side” of the memorial on Friday.

On Saturday morning, Melissa Owen, who lives near Sasabe, flew in a helicopter over nearby wall construction sites. As of 8:40 a.m. on Saturday, “they were actively carving through the mountains,” Owen said. She could not see any bollards being installed, but other construction work appeared to be continuing “as usual” with trucks, bulldozers, excavators and water trucks operating both to the east and west of Sasabe, she said.

The Star reached out to the Corps to clarify whether the work was normal wrap-up work at a construction site, which the Biden proclamation appeared to allow, or some sort of attempt to defy Biden’s order. Corps spokesman Jay Field reiterated a portion of the Corps’ statement from Thursday saying the only work that would be done over the next few days would be to prepare sites for the suspension of work.

“We are not installing any additional physical barriers,” Field said.

The owner of the contracting company building the wall near Sasabe did not respond to an inquiry from the Star on Saturday morning.

Project review coming

In addition to pausing construction, Biden’s order also ended the national emergency Trump declared in February 2019, which was used to divert roughly $10 billion from the Defense Department to wall construction. Another $5 billion came from congressional appropriations, according to CBP.

During the pause, Biden administration officials will conduct a “careful review of all resources appropriated or redirected to construct a southern border wall.” He directed officials to assess the “legality of the funding and contracting methods used to construct the wall.”

The Supreme Court is scheduled to hear arguments next month about the legality of diverting Defense Department funds after Congress denied the bulk of the Trump administration’s request for wall funding.

Officials can make exceptions to the pause in construction “to avert immediate physical dangers” or to ensure that funds appropriated by Congress “fulfill their intended purpose,” according to Biden’s proclamation.

Officials will develop a plan for the “redirection” of wall funding within 60 days. They must then “take all appropriate steps to resume, modify or terminate projects and to otherwise implement the plan.”

The financial cost of canceling the contracts is not yet clear. The Associated Press quoted a Senate aide as saying fees would be negotiated with contractors, and the administration would seek to spend whatever’s left on related uses on the border, such as roads, lights, sensors and other technology.

Dinah Bear, a Tucson resident who worked for Democrat and Republican administrations for many years on environmental law and policy, said her “immediate focus” was on making sure contractors comply with Biden’s order.

Photos: Monsoon Storm Washes out Border Wall Construction

U.S./Mexico border in the San Pedro River National Conservation Area

Updated

Rains from a monsoon storm that rolled through on Saturday August 1 buried much of the foundation work in mud for the construction of the U.S./Mexico border wall across the San Pedro River near Hereford, Ariz. Photos taken: August 3, 2020.

U.S./Mexico border in the San Pedro River National Conservation Area

Updated

Rains from a monsoon storm that rolled through on Saturday August 1, damaged a road used by Border Patrol and construction work at the San Pedro River near Hereford, Ariz. August 3, 2020.

U.S./Mexico border in the San Pedro River National Conservation Area

Updated

Rains from a monsoon storm that rolled through on Saturday August 1, damaged a road used by Border Patrol and construction work at the San Pedro River near Hereford, Ariz. August 3, 2020.

U.S./Mexico border in the San Pedro River National Conservation Area

Updated

A photo from June 24, 2016 shows vehicle barrier or "Normandy" type fencing lines the U.S./Mexico border in the San Pedro River National Conservation Area inside the Coronado National Memorial park in Arizona.

U.S./Mexico border in the San Pedro River National Conservation Area

Updated

The photo taken on July 8, 2020 shows construction on the U.S./Mexico border fence over the San Pedro River in the San Pedro River National Conservation Area near Hereford, Ariz. Cement blocks are placed within a trench dug across where the river flows. Mexico is on the right.

U.S./Mexico border in the San Pedro River National Conservation Area

Updated

Rains from a monsoon storm that rolled through on Saturday August 1 buried much of the foundation work in mud for the construction of the U.S./Mexico border wall across the San Pedro River near Hereford, Ariz. August 3, 2020.

U.S./Mexico border in the San Pedro River National Conservation Area

Updated

Rains from a monsoon storm that rolled through on Saturday August 1 buried much of the foundation work in mud for the construction of the U.S./Mexico border wall across the San Pedro River near Hereford, Ariz. On the left is Mexico. August 3, 2020.

U.S./Mexico border in the San Pedro River National Conservation Area

Updated

Rains from a monsoon storm that rolled through on Saturday August 1 buried much of the foundation work in mud for the construction of the U.S./Mexico border wall across the San Pedro River near Hereford, Ariz. Debris from another storm is seen caught up in tree trunks on the Mexico side of the border. August 3, 2020.

U.S./Mexico border in the San Pedro River National Conservation Area

Updated

Rains from a monsoon storm that rolled through on Saturday August 1 buried much of the foundation work in mud for the construction of the U.S./Mexico border wall across the San Pedro River near Hereford, Ariz. August 3, 2020.

U.S./Mexico border in the San Pedro River National Conservation Area

Updated

Rains from a monsoon storm that rolled through on Saturday August 1 buried much of the foundation work in mud for the construction of the U.S./Mexico border wall across the San Pedro River near Hereford, Ariz. A pattern to flowing water is scene in the riverbed of the San Pedro River with the border of Mexico in the bakcground on August 3, 2020.

Future of border wall about to be handed over to voters

UpdatedWhen voters cast their ballots in the Nov. 3 presidential election, they will choose between two strikingly different plans for the border wall in Arizona and border security in general.

On one hand, the Trump administration plans to spend $15 billion to build hundreds of miles of 30-foot-tall wall along the U.S.-Mexico border, which includes filling gaps in the wall already standing in Arizona. On the other hand, Joe Biden plans to stop building the wall and focus instead on beefing up screening technology at ports of entry and building surveillance towers in remote areas.

The border wall played a central role in President Trump’s campaign in 2016, and he continues to tout the wall at rallies across the country. He tells crowds, “It’s like magic” and is “working beyond our wildest expectations.” In response they chant: “Build that wall!”

While Trump claims Biden and other Democrats want open borders, Biden accuses Trump of being obsessed with a wall he says “does nothing to keep Americans safe” and won’t stop smugglers from digging tunnels or flying drones across the border.

Biden told reporters in early August, “There will not be another foot of wall constructed in my administration.” Instead, he would put his efforts toward “making sure we use high-tech capacity to deal with it at the ports of entry; that’s where all the bad stuff is happening.” He has not said he would tear down the wall, but he likely would face intense pressure to do so if he is elected.

For voters in Wisconsin, Virginia and other states far from the U.S.-Mexico border, the presidential candidates’ comments may amount to little more than political rhetoric that prompts either cheers or groans, depending on the listener’s political perspective.

For Southern Arizona residents, the vote on Nov. 3 will determine the future of the border wall and set the tone for how federal agencies spend billions of taxpayer dollars to address drug smuggling and illegal border crossings for at least the next four years.

To analyze what’s at stake, the Arizona Daily Star spoke with border residents and Customs and Border Protection officials, reviewed court records and CBP statistics, and made two dozen trips to border wall projects since construction started in the summer of 2019.

Wall raises no shortage of opinions

Standing next to the wall, you have to crane your head back to see the top of it. The wall is made of steel poles, known as bollards, that extend 30 feet up from the ground. Each bollard is 6 inches wide and filled with concrete and rebar. To allow Border Patrol agents to see into Mexico, the bollards are separated from one another by 4 inches of space.

A wide steel plate is fitted to the top of the wall to make it more difficult to climb over. To deter tunnel digging, the concrete foundation of the wall extends 6 to 10 feet into the ground. Lighting and sensors help agents detect activity near the wall, and new roads will help them respond faster.

Most of the 190 miles of wall built so far in Arizona replace head-high vehicle barriers or fencing that stands 10 feet to 18 feet tall. When construction is completed, Arizona will have more than 230 miles of wall, at a cost of roughly $4.5 billion.

As the election nears, there is no shortage of opinions about the wall among residents of border towns, despite the wall taking a backseat to the coronavirus and other issues in the election season.

“Build the Wall and Crime will Fall,” proclaimed an electronic billboard near Wellton, a small town near Yuma about 25 miles north of where contractors built the 30-foot-tall wall behind a much shorter metal-mesh fence. In Tucson, yard signs demand “No Border Wall,” and Tohono O’odham protesters carried banners calling for “No Wall on O’odham Land” after briefly stopping wall construction southwest of Tucson last month.

The Star regularly receives calls and emails from readers who support or oppose the border wall, including a SaddleBrooke resident who said completing the wall can’t come soon enough, along with fully funding the Border Patrol. A Tucson resident called the wall a blight on the landscape paid for with money stolen from the military. An Oro Valley resident said he was pleased to have the wall in place and that open borders were bad for America.

Brad Finn, a Vietnam veteran who has lived next to the border near the San Pedro River in Cochise County since the late 1990s, said the border fence installed a decade ago “keeps us safe,” but he worried the new wall would block wildlife migrations.

“I’m not sure how the Mexican jaguars are going to get through, unless they get a key to the gate,” Finn said as he stood on a dusty road and watched a crane replace an 18-foot-tall wall panel with a 30-foot-tall panel.

The vehicle barriers being replaced closer to the San Pedro River let animals, and humans, easily cross the border. The new wall projects in the area will connect with fencing in Douglas and Naco to create a roughly 75-mile long barrier that will be virtually impossible for deer, bear, bobcats, mountain lions or any animal larger than a jackrabbit to cross.

“It isn’t like it was 20 years ago,” Finn said. Back then, only about four Border Patrol agents worked in the area each night, trying to catch large groups of people looking for work or hauling marijuana loads. Now, it’s closer to 40 agents each night looking for small groups in camouflage.

Standing in a hangar on Davis-Monthan Air Force Base surrounded by Customs and Border Psrotection helicopters and surveillance planes, Border Patrol Chief Rodney Scott said the new wall will prove effective.

“Any place we’ve ever installed border wall, it’s actually improved the ability of every individual agent to cover more border, to secure more border in their shift than they could without it,” Scott said.

Rather than an impenetrable barrier, the new wall intimidates some people from trying to cross the border and slows down those who take the risk, Scott said.

“It stopped most older people and most younger kids. When they walk up and they see a 30-foot-high wall, it stops them,” Scott said. “It doesn’t always stop the 22-year-old. It doesn’t always stop the super-agile. But you know what? Now it’s one (person),” instead of large groups crossing together.

Melissa Owen, who lives on a ranch near Sasabe where new wall is going up, said she supports border security, but the new wall is a “monstrosity” that is unpopular with her neighbors.

“Anyone who actually knows the situation here knows that heightened security at ports of entry, where most illegal substances come into the U.S., a sensible program of surveillance technology, and a sane and equitable immigration policy are the best answers to the ‘crisis on the border,’” Owen said.

During the last year of wall construction, far fewer families and children were stopped while crossing the border in remote areas, according to CBP statistics. That trend began before wall construction started in Arizona, due largely to Trump administration policies cracking down on asylum seekers and the Mexican government stopping asylum seekers from reaching the U.S. border.

Border Patrol agents are catching more single adults trying repeatedly to cross the border, including 8,000 in September when 170 miles of wall had been built in Arizona. CBP officials say this is the result of pandemic-related policies that involve quickly expelling Mexican migrants, who then turn around and try repeatedly to cross the border.

As for drugs, most hard drugs like meth, fentanyl and heroin are smuggled through ports of entry rather than through the desert where the wall is being built, as has been the case for decades, CBP statistics show. Marijuana, far and away the most common drug smuggled through the desert, plummeted in the last decade as the legal marijuana industry expanded in Arizona and other states.

The stakes

Arizona has been at the center of the Trump administration’s wall-building efforts since construction started last summer, due in part to the accessibility of federal land along Arizona’s border with Mexico.

The wall now crosses the San Pedro River in Cochise County, much to the disappointment of bird-watchers and nature enthusiasts who enjoy one of the last free-flowing rivers in the Southwest. Contractors are plowing through mountainsides a few miles west of the river on the Coronado National Memorial, as well as in Guadalupe Canyon in the county’s southeastern corner and the mountains west of Nogales. The wall runs along most of Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument and the Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge southwest of Tucson.

Near Yuma, only a few areas remain without a new wall, most notably a stretch along the Colorado River that the Cocopah Indian Tribe considers sacred. Near Tucson, the wall will run along most of the border except for a few mountains, the San Rafael Valley east of Nogales, 62 miles on the Tohono O’odham Nation, and urban areas like Nogales and Douglas.

The head of Customs and Border Protection, Mark Morgan, told the Star on Wednesday that officials are considering building more wall in Arizona, including a second layer of wall in urban areas and in the “open gap” on the Tohono O’odham Nation.

“Wherever we don’t have a wall system, that’s where the cartels are exploiting. We’re already seeing that on the Tohono O’odham Nation,” Morgan said.

“We’re going to continue to have ongoing dialogue with the leaders of the Tohono O’odham Nation to come up with a viable solution there,” Morgan said.

Tribal officials have opposed the idea of replacing head-high vehicle barriers on the reservation with new wall, saying last week that the wall was “destroying our environment, desecrating sacred places, and physically separating our people.”

Tohono O’odham Nation Chairman Ned Norris Jr. said Morgan was “either misinformed” or “purposely misleading the public” about dialogue between CBP and the Tohono O’odham Nation.

“There is no ongoing dialogue, nor has CBP ever had required consultations with the Nation regarding the ongoing destruction of sacred O’odham sites along the border,” Norris said. “CBP has never offered a wall proposal to the Nation and has repeatedly stated in meetings when asked that they have no plans to build a wall on the Nation’s lands.”

“The Nation continues to expend extraordinary resources to protect the U.S. border, and has already agreed to viable solutions such as vehicle barriers, Integrated Fixed Towers, and other measures,” Norris said. “The Nation’s position on a fortified wall is clear and we agree that consultations on this issue need to start immediately.”

The reservation has long been a site of illegal border crossings and drug smuggling, federal court records in Tucson show. Those records also show O’odham police working with federal agents on task forces and busts made with the help of sensors and cameras on the reservation and Border Patrol checkpoints that ring the reservation.

With regard to building a second layer of wall in urban areas, Morgan did not cite any plans for specific cities in Arizona. A second layer of wall already is going up along about 1 mile of the border in downtown Naco, but no plans have emerged for Nogales or Douglas.

A border fence has run through downtown Nogales for several decades, evolving from chain-link fence to Vietnam War-era landing mats and now the current version made of 18-foot-tall bollards built nearly a decade ago. Camera towers run by CBP are positioned on either side of the downtown port of entry.

“Honestly, I think that’s overkill,” Nogales Mayor Arturo Garino said of the possibility of building a second layer of wall. “I can’t see a 30-foot wall going through downtown Nogales.”

Garino said he supports border security and pointed out that Nogales police and Santa Cruz County sheriff’s deputies regularly work with the Border Patrol to combat cross-border crime.

If CBP were to decide to build a second layer of wall in downtown Nogales, it likely would block off the road that runs along the border fence, which is the main access point for several neighborhoods, he said.

“As a city, we would have to have a serious conversation with CBP,” Garino said.

The wall in election season

Despite the importance of the wall to border communities, it has faded somewhat in the presidential election as other issues took center stage.

The wall is a mainstay at Trump rallies, but it usually only takes up a minute or two of hourlong speeches. Trump told crowds in Nevada, Wisconsin, Ohio, and elsewhere that the wall is working, it will be finished soon, and Democrats want open borders.

Biden talks about it even less. His views on the wall and border security are described in detail on the campaign website, but most of his public comments on the wall came during an interview with the National Association of Hispanic Journalists and the National Association of Black Journalists in early August.

Neither campaign answered questions from the Star about the wall in Arizona. Instead, they provided general background information and referred the Star to their campaign websites.

“It seems to feature less prominently in this campaign than it did in the 2016 campaign,” said Jessica Bolter, a policy analyst at the Migration Policy Institute, a nonpartisan think tank in Washington, D.C.

Public concern about immigration also has been dwarfed by the coronavirus pandemic and the poor state of the economy, she said. The Trump campaign also sees “internal threats to dwell on,” she said, such as protests that Trump opposes.

At the same time, the administration has sped up border wall construction, she said. More than half of the 360 miles of wall built during the Trump administration were built since April.

If Trump is elected, Bolter expects he will continue building nearly 740 miles of border wall. If Biden wins, she expects he will adopt the “mainstream Democratic position” on border security and invest in technology.

Biden said he would stop wall construction, but he has not been clear about whether he would cancel wall contracts or just not award any new ones.

Given the high visibility of the wall, “I suspect that this is something that Biden will try to deliver on pretty quickly,” Bolter said.

Cal Glover, a member of the People Helping People group that advocates against the militarization of the border in Arivaca, just north of where about 40 miles of wall are being built, said he is voting for Biden, but “I’m not happy about it.” Biden may not build more wall, but he has not said he would tear it down, Glover said.

“It’s not going to make it worse, but it’s not going to help,” Glover said of a possible Biden presidency.

The Army Corps of Engineers, which manages wall contracts, did not clarify what type of costs taxpayers should expect if Biden were to cancel ongoing wall projects.

“We cannot speculate on the impacts of terminating border wall construction contracts,” the Corps said in response to an inquiry from the Star.

Federal regulations allow the government to “exercise its right to terminate the contract for its convenience,” the statement from the Corps said. However, “the contractor is entitled to submit a request for termination settlement costs.”

Measuring success

While Trump says the wall helped “achieve the most secure border in history,” Biden calls it a poor use of resources when most contraband is smuggled through legal ports of entry.

Biden’s view of drug smuggling is consistent with CBP statistics for Arizona, at least as far as hard drugs like meth and heroin are concerned. Morgan, the head of CBP, and Scott, the head of the Border Patrol, maintain the wall will be successful when viewed as part of a “multilayered strategy” that includes agents and technology.

In a decadeslong pattern, the vast majority of seizures of hard drugs occur at Arizona’s ports of entry, rather than in remote areas where the new wall is going up, CBP statistics show.

Customs officers at Arizona’s ports of entry intercepted 1,100 pounds of fentanyl in the first 11 months of fiscal 2020, five times as much as Border Patrol agents in the Tucson and Yuma sectors caught in the deserts and highways. Customs officers also caught five times as much heroin, seven times as much cocaine, and three times as much meth.

In Arizona, that pattern shifted slightly in the past year as Border Patrol agents saw more meth smuggled in backpacks through the desert. Federal officials told the Star that smugglers likely were trying to replace revenue lost from a sharp decline in marijuana smuggling in recent years. Seizures of marijuana by Border Patrol agents in Arizona dropped steadily from 1.25 million pounds in fiscal 2013 to 48,500 pounds in the first 11 months of fiscal 2020.

The Star asked Morgan whether the administration had a measure to show the public whether the wall was a success, such as a drop in illegal border crossings.

“When we have that multilayered strategy at effective levels in strategic locations, we will see that output: Seizures go down, illegal immigration goes down, assaults on agents go down,” Morgan said.

Success should be measured in terms of how CBP interacts with drug cartels to “shape their behavior and guide them where we want them to go,” Morgan said.

In terms of stopping people from crossing the border in Arizona, the effect of the wall is unclear so far.

Apprehensions of people crossing the border illegally, which is used as a proxy for total illegal crossings, in Arizona fell fairly steadily from 616,000 in fiscal 2000 to 51,500 in fiscal 2017. That period saw more Border Patrol agents stationed in Arizona and vehicle barriers, fencing, and surveillance towers installed along much of the border, as well as economic growth in Mexico that lessened the need to head to the United States.

For fiscal 2020, agents in Arizona reported nearly 75,000 apprehensions, including more than 54,000 single adults. That total was a sharp decrease from the previous fiscal year when agents made 132,000 apprehensions. Many of those apprehensions were of asylum-seeking families and children who generally sought out Border Patrol agents, rather than tried to evade them.

Last month, when 170 miles of new wall had gone up in Arizona, agents stopped more than 8,000 single adults, compared to about 1,100 members of families and unaccompanied children.

The wall will cut down on the number of migrants agents apprehend at any one time, Scott said, which will give agents more time to interview them and gather information about smuggling organizations.

Scott said he had seen people climb over the wall and cut through it, which “takes about 20 minutes, depending on the tools.” But if they climb over the wall, they will be easier to catch than “somebody that stood there and said ‘go’ and sprinted north.”

If smugglers manage to cut through one of the bollards, “you can squeeze one person through at a time,” rather than large groups that would rush through openings in metal panel fencing years ago.

A “perpetual” emergency

One key difference between the Biden and Trump campaigns involves the emergency declaration that allowed Trump to pull $10 billion from the Defense Department to build the border wall.

The Biden campaign says his administration would “end the so-called National Emergency that siphons federal dollars from the Department of Defense to build a wall.”

President Trump signed the declaration in February 2019. The declaration came after a dispute with Democrats in Congress over wall funding led to a partial government shutdown.

Trump’s rhetoric about the border wall often conjures up images of violent gang members, and the emergency declaration briefly cited the border as a “major entry point for criminals, gang members and illicit narcotics.”

But the formal justification for funding the wall, as well as the wall’s apparent effects, were aimed at stopping asylum-seeking families from crossing the border.

“In particular, recent years have seen sharp increases in the number of family units entering and seeking entry to the United States and an inability to provide detention space for many of these aliens while their removal proceedings are pending,” the declaration read.

Due to the “gravity of the current emergency situation, it is necessary for the Armed Forces to provide additional support to address the crisis,” it read.

The Defense Department ended up funding most of the wall projects in Arizona, according to the Corps. Contracts for 88 miles of wall near Tucson, at a cost of $2.2 billion, went to Southwest Valley Constructors, a New Mexico-based affiliate of construction giant Kiewit.

Contracts for another 74 miles of wall in Arizona, at a cost of $1.8 billion, went to Fisher Sand and Gravel, a North Dakota-based firm with offices in Tempe. The first of those contracts resulted in a probe by the Defense Department’s inspector general after members of Congress objected to reports that Trump pressured officials to award contracts to Fisher. That probe is ongoing.

Another $425 million went to BFBC, an affiliate of Montana-based Barnard Construction Co., for 33 miles of wall near Yuma. A few other projects near Yuma were funded by congressional appropriations.

At the time of the emergency declaration, hundreds of thousands of families from Honduras, Guatemala, El Salvador and other countries were arriving at the U.S.-Mexico border to ask for asylum. The Trump administration implemented numerous policies aimed at keeping asylum seekers from entering the United States, such as forcing them to wait in Mexican border towns like Nogales, Sonora.

The premise of the Trump administration’s approach to asylum seekers is that they are presenting fraudulent asylum claims, a point CBP officials emphasized at Davis-Monthan last week. Federal court records in Tucson and Yuma showed cases of using false identification documents or traveling with someone else’s child, but they represented a tiny portion of the thousands of families who asked for asylum.

The Star spoke with asylum seekers last year at the former Benedictine Monastery in Tucson, where 20,000 asylum seekers were housed for a few days before they left to live with friends and families in other cities and await their immigration court hearings. Dozens of other families told the Star their stories after the Trump administration forced them to wait in Nogales, Sonora, for their chance to speak with U.S. officials.

Some families said they fled Mexican towns after local mafias murdered their relatives. Some left Honduras after gangs took over their neighborhoods and tried to recruit their children. Cubans told the Star about living under a dictatorship that repressed political speech and limited the amount of money they could make. Venezuelans said food was running out and electricity was unreliable due to corrupt government.

Since mid-2019, the number of families trying to cross the border has plummeted, but Morgan told the Star last week that the emergency is ongoing.

The Star asked Morgan if border residents should expect to live under a perpetual state of emergency, despite the rationale for the declaration disappearing.

“Here’s when the emergency ends, in my opinion: When we have Congress step up and pass meaningful legislation to end the crisis,” Morgan said. “To once and for all send a message to anyone that is even anticipating illegally entering: You are not going to be allowed in and there will be consequences. Until we have statutory reform, I think we’re going to be in perpetual crisis.”

Federal judges are pushing back on the Trump administration’s pulling of money from the Defense Department after Congress rejected his request. The administration is likely to appeal to the Supreme Court, which previously let stand the administration’s funding decision.

The 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in early October that the Trump administration overstepped its authority when it moved billions of dollars from the Defense Department’s construction fund to build the border wall. Those funds were used to build sections of wall in Yuma, California and Texas. The appeals court judges said the Trump administration failed to show how the wall projects were “necessary” for the Defense Department.

The D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled on Sept. 25 that the House of Representatives had standing in a lawsuit alleging the Trump administration violated the House’s constitutional power over funding federal activities.

“To put it simply, the Appropriations Clause requires two keys to unlock the Treasury, and the House holds one of those keys. The Executive Branch has, in a word, snatched the House’s key out of its hands,” the D.C. judges wrote.

While those lawsuits play out and voters consider how to cast their ballot, Morgan warned that the coronavirus pandemic would lead to more waves of immigration from Mexico and Central American countries.

“We’re seeing economic conditions in the Western Hemisphere worsen dramatically,” Morgan said “So we have seen lately, as we anticipated because as economic conditions worsen, that drives illegal immigration. We’re starting to see the numbers go up.”