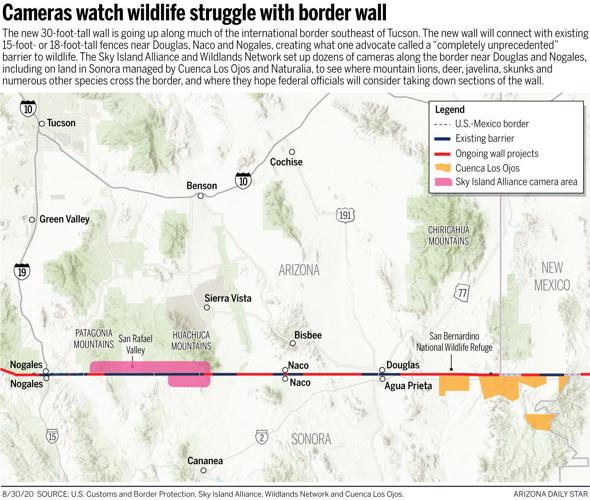

While contractors build a 30-foot-tall steel border wall southeast of Tucson, wildlife advocates are racing to document where animals cross the border most often and hoping federal officials will consider taking down sections of wall that block those corridors.

When the new wall projects are finished in Cochise County, they will seal off nearly 75 miles of the border to animals larger than a rabbit, despite that area being the home or migratory route of mountain lions, deer, bear and numerous other species. Where sections of the new wall are in place, wildlife advocates already have seen javelina, bobcats, and other animals spend hours struggling fruitlessly to find a way through the wall.

To identify the corridors most used by wildlife, the Wildlands Network in January set up scores of motion-activated wildlife cameras in the San Bernardino Valley in southeastern Cochise County, where contractors already built some 15 miles of new wall. Meanwhile, the Sky Island Alliance is running a similar camera project east of Nogales in the San Rafael Valley and the nearby mountains, where Customs and Border Protection officials are trying, so far unsuccessfully, to obtain funding for a wall.

The wall in the San Bernardino Valley is a “completely unprecedented” barrier to wildlife crossings, said Myles Traphagen, borderlands project coordinator for the Wildlands Network.

“You have a whole regional population of wildlife that right now doesn’t know what’s going on,” Traphagen said as he checked a camera strapped to a tree on the San Bernardino National Wildlife Refuge on Monday.

In the previous month, the camera snapped photos of mountain lions, bobcats, javelina, raccoons, hooded skunks, mule deer and other species walking among the cottonwoods and willow trees on the sandy streambed of Black Draw. The contractor has not yet finished the wall structure across the stream, making it a rare place in the valley where large animals can still cross the border.

Until recently, those animals could have walked under or through the head-high barriers set up in the valley in 2008 to stop smugglers from driving drug-laden vehicles across the border. Now, the 30-foot-tall wall, made of 6-inch-wide steel bollards separated by 4 inches of space, runs across most of the valley. Eventually, it will connect with other new sections of wall and 18-foot-tall fencing installed years ago in Douglas and Naco.

A Wildlands Network camera shows two pumas on the San Bernardino National Wildlife Refuge.

Since last summer, contractors have built about 60 miles of new wall in the Border Patrol’s Tucson Sector, just under half of the 137 miles of wall planned for the sector’s 262 miles of border.

CBP officials say they will install small openings 8.5 inches by 11 inches to allow animals to cross the border. They did not respond to an inquiry from the Star about those openings or whether any other steps were taken to incorporate wildlife crossings into wall plans. Judging by the various trips the Star has taken to border wall projects in the past year, the openings are few and far between.

As for wildlife passages for larger animals, such as the jaguar, federal agencies are working together to identify locations and strategies that would accommodate those species, a spokeswoman for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service told the Star in April.

Projects of this magnitude normally would require an extensive review of their impact on the environment, such as the nearly 200-page report compiled in 2008 for 5 miles of 15-foot-tall border fencing near Lukeville, a small border town 150 miles southwest of Tucson. But the Trump administration waived dozens of laws to speed up wall construction, including the requirement to review environmental impacts.

Instead of a formal review, CBP officials told the Star last September that they would publish an Environmental Stewardship Plan. However, a year later, that plan remains just a promise, even as the 20-mile wall project in the San Bernardino Valley nears completion.

Contractors have already built some 15 miles of new U.S.-Mexico border wall in the San Bernardino Valley in southeastern Cochise County.

GATHERING EVIDENCE

Some of the most poignant evidence of the wall’s impact on wildlife comes from cameras set up across the border from the San Bernardino Valley.

The conservation organization Cuenca Los Ojos, which has managed land on the Sonoran side of the border since the 1990s, is working with the Wildlands Network on the camera project.

In February, cameras operated by Cuenca Los Ojos showed a family of javelinas pacing back and forth for nearly five hours as they tried to find a way through the wall. The next month, cameras showed a pair of bobcats split by the wall, with one bobcat walking on either side of the wall, unable to reach each other.

Similar scenes have unfolded with mule deer, badgers, mountain lions, and other species, said José Manuel Pérez, director of operations at Cuenca Los Ojos.

Wildlife from Mexico used to cross the border regularly to drink from a windmill-powered well a few miles west of the San Bernardino refuge, but the new wall blocked them from reaching the well, Pérez said. He and his associates rehabilitated an old well on the Mexico side and placed a camera nearby.

“We saw immediately how the wildlife responded to the water,” he said, listing bobcats, mountain lions, javelinas and various birds showing up at the well.

Perhaps the most distressing image to surface recently came from the Lukeville area, where a 63-mile wall project is underway. A photo that circulated widely on social media showed a dead mule deer next to a long stretch of border wall, likely struck by a vehicle as it wandered along the wall.

Sky Island Alliance community science manager Zoe Fullem, left, and volunteer Bill Bemis hike to a camera in the Patagonia Mountains.

These were the types of situations local residents, wildlife advocates and government agencies brought to the attention of CBP officials, according to a “stakeholder feedback report” released last week by CBP.

Nearly 300 comments dealt with the impact of wall projects on animal and plant species, according to the CBP report. Of those, 272 comments opposed wall construction, “stating the project would have a negative impact on wildlife, particularly on wildlife corridors and migration.” CBP reported 114 of those comments “mentioned the jaguar, whose habitat transverses the border between Arizona and Mexico.”

Pérez said cameras on land managed by Cuenca Los Ojos snapped a photo of a jaguar early last year. Five male jaguars have been photographed in Arizona since 1996.

The cameras operated by the Wildlands Network and the Sky Island Alliance are part of an effort to fill the void left after the Trump administration waived the requirement to show the wall’s impact on wildlife.

A deer watches the road after grazing on foliage in the Patagonia Mountains. Deer are just one of many species having their migration patterns affected by the new wall.

The goal is to gather “fact-based information on changes in wildlife movement and border wall impacts so that appropriate decisions can be made” by land managers and federal officials, Traphagen said.

In a similar vein, the Sky Island Alliance set up a grid of cameras along 34 miles of the border in March. The grid runs from the Patagonia Mountains, across the San Raphael Valley, to the Huachuca Mountains.

They are looking for the most important wildlife corridors, which will “clarify conservation priorities,” said Emily Burns, the organization’s program director.

“Even if it isn’t influencing at the moment the current administration about wall construction,” the data gathered by the cameras will be important in future discussions of the wall, Burns said.

She anticipates a “series of compromises” after the border wall is completed. The corridors identified by the camera project “will be the places we’ll be championing where we need to tear down the wall,” she said.

A bear track was found in the mud around a pond in the Patagonia Mountains near Nogales, Arizona. The Patagonia Mountains are one of the few ranges to span the border.

“That would be great,” Pérez said about the possibility of removing small sections of the wall. “It’s really hard for us to see all the effects of the wall.”

The Trump administration is pushing ahead with plans to complete 450 miles of wall by the end of the year. So far, more than 275 miles of wall have been completed along the U.S.-Mexico border, according to CBP.

Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden told reporters in early August he intended to halt border wall construction if elected, but he stopped short of saying he would remove the wall, the Dallas Morning News reported.

LOOKING AHEAD

The Sky Island Alliance is trying to establish baseline data for wildlife in the San Rafael Valley, in case funding ever comes through to build the border wall there, Burns said.

It is working with Naturalia, a conservation organization that manages Rancho Los Fresnos just south of the border, Burns said. The photos are downloaded and a team of more than 30 volunteers help sort the photos. Experts then make the final identification of the animals.

The eastern part of the grid in the Huachuca Mountains starts not far from where the soon-to-be 75 miles of barriers in Cochise County will end.

The Patagonia and Huachuca mountains are two of the few ranges that span the Arizona-Sonora border. They contain vital corridors for numerous species, including a bear that left paw prints in the mud around a watering hole spotted by volunteer Bill Bemis on Tuesday.

Bill Bemis and Zoe Fullem, of the Sky Island Alliance, look at a map marking spots where cameras are set up along the border wall to identify wildlife corridors.

The Sky Island Alliance has had cameras in the area for years, but they mostly were set up near springs where animals tend to congregate, said Zoe Fullem, the organization’s community science manager.

The new grid of cameras is spread evenly across the valley and mountains to find previously unknown corridors, she said as she checked a camera Tuesday among the oak and manzanita trees on the eastern slope of the Patagonia Mountains.

“There hadn’t been a study like this anywhere in Arizona along where the wall was going to be built,” Fullem said.

The cameras showed animals aren’t always found just near water or in canyons that would be likely migration routes, Bemis said.

“We discovered there was a lot of migration that we wouldn’t have expected in different spots,” Bemis said.

So far, they have seen more than 70 different species, Fullem said.

“Almost every single check, we see a new species that we haven’t seen in the past five months,” Fullem said.