Southern Arizona migrant-aid groups and humanitarian volunteers on the border are facing an escalation in confrontations with armed vigilantes and right-wing propagandists, who are increasingly publishing videos — sometimes garnering millions of views — that falsely accuse the volunteers of being in league with traffickers, terrorists and Mexican organized crime.

Researchers say an anti-government convoy that headed to multiple sites along the southern border over the past week has invigorated extremists, as has dehumanizing, racist rhetoric from conservative politicians stoking fear about migrants.

A Tucson migrant-aid shelter has had to boost security after being targeted for harassment by multiple right-wing media personalities.

“It has now required Pima County to put more security around that facility,” said Pima County Supervisors Chair Adelita Grijalva. “Many of the people that are at Casa Alitas are volunteers. Many of them are older. We’re always concerned for everyone’s safety and want to make sure people feel comfortable.”

Over the last month, Humane Borders has seen a spike in efforts to destroy its water stations, which aim to prevent migrant deaths in the Southern Arizona desert.

“It comes in waves. We had a wave last spring and now it’s back,” said Laurie Cantillo, board chair for the Tucson nonprofit. The group’s water barrels have been drained, shot and stabbed. Vandals have kicked off or removed the spigots to prevent access to water, written “poisonous” in Spanish on the barrels and toppled the tall blue flags which mark the stations.

Those water stations are available to anyone in need — whether migrants, hikers or hunters — in dangerously remote areas, Cantillo said.

“Everyone is welcome to it,” she said. “To deny water to someone, knowing another person may die as a result, I don’t have any words except to say that’s pure evil.”

In Yuma County last week, local law enforcement braced for the Feb. 3 arrival of the “Take Our Border Back” convoy, a highly publicized series of rallies promoted by anti-immigrant and anti-government groups, some of whom claim to be part of “God’s Army.”

Yuma County Sheriff Leon Wilmot said local law enforcement was working with emergency services and Border Patrol to ensure Saturday’s rally would be safe for the community.

As of late Saturday afternoon, about 700 convoy vehicles had arrived in Yuma County, though more were expected, said a public affairs official with the sheriff’s office. The estimated 1,400 attendees were gathered to hear speeches at an outdoor event space, with a view of the border wall.

Planners and supporters of the convoy are elevating conspiracy theories about humanitarian volunteers and pushing the racist “Great Replacement” theory — which asserts there’s a secret plot to replace white populations with non-white populations — and terminology like “invasion” to describe migrant arrivals.

“This convoy has animated the far-right, anti-immigrant movement,” said Freddy Cruz, a researcher with the pro-democracy advocacy group Western States Center, in a Thursday press call. “We hope both elected representatives and community leaders stand together to oppose such actions, which only fuel hate and put marginalized communities in danger.”

In the call, Cruz highlighted the targeting of Arizona aid groups, including the Samaritans, Humane Borders and No More Deaths.

Pima sheriff briefed on fears

Local aid workers say they’ve been alarmed by the “frightening” rise in these confrontations with armed vigilantes. They’re also concerned about being “doxxed” — having identifying information shared widely online, to encourage harassment — by live-streamers who are publishing videos of volunteers’ faces and vehicles, while falsely accusing them of being pedophiles and traffickers.

On Thursday, members of the Samaritans sat down with Pima County Sheriff Chris Nanos to discuss their fears and ask for support.

“I appreciate what they’re doing, which is taking care of people in need,” Nanos said after the meeting. “They’re staying out of the politics. They’re giving them water and giving them food. They are not taking them into the country. In fact most of the time, they just sit there (with migrants) and contact Border Patrol.”

The surge in aggressive encounters is partly driven by politicians using the border to score political points in an election year, Nanos said.

“I think it’s not going to die down as long as the border is being politicized the way it is,” he said.

Gail Kocourek, a long-time volunteer with Tucson Samaritans, said aid workers were reassured by Nanos’ empathy and the suggestion that volunteers communicate their schedule and locations with his office, so deputies can be ready to respond.

“What’s frightening about them (vigilantes) is they carry guns; we carry water,” said Kocourek, who spends three days a week at the border providing water, food and blankets to migrants and reporting their presence to border agents.

Armed vigilantes have screamed at her, telling her she’s a pedophile and is on the cartel’s payroll, Kocourek said, adding with a laugh, “They must have the wrong address, because I’ve never gotten a check.”

Experts say the risk of extremist violence is real, especially as more right-wing media personalities amplify baseless conspiracy theories, seizing on anxiety about migration to fundraise and boost their social-media followings.

In 2022, Kocourek was at the border south of Arivaca with a film crew, including a Guatemalan man who was a legal permanent resident, she said. A truck driven by QAnon adherents spotted the man and drove up beside her car, screaming, “Illegal alien!” and attempted to run her off the road, until they were intercepted by Border Patrol.

The QAnon group then published a video asking their social-media followers to track down Kocourek, whom they described as “running ops for the cartel.”

When people ask what she’s afraid of at the border, Kocourek says it’s not the exhausted, desperate migrants she encounters who cause her to worry.

“It’s white guys with guns,” she said. “They seem to thrive off of fear and hate. ... I’m sorry they’re so afraid. But I’m afraid of them.”

Harmful political rhetoric

Across the U.S., anti-immigrant sentiment is on the rise, fueled by a surge in migrant arrivals, rampant misinformation and an escalation in dehumanizing rhetoric — especially from U.S. politicians — that experts on extremism say puts migrants, and U.S. citizens of color, at risk.

Some conservatives are embracing language like “invaders” and “fighting-age men” to describe migrants. In December former President Donald Trump said immigrants are “poisoning the blood of our country,” echoing white supremacist rhetoric and the writings of Hitler.

Last month Republican state Sen. Janae Shamp of Goodyear introduced a bill, SB1231, that would make it a state crime in Arizona for anyone to enter the U.S. other than at a port of entry and authorize local or state police to enforce the law.

Shamp told Capitol Media Services, “What was once an issue is now an invasion.” She did not respond to the Arizona Daily Star’s request for comment on her use of the term.

Pinal County Sheriff Mark Lamb, a Republican running for Kyrsten Sinema’s U.S. Senate seat, has also stirred anger against the non-government organizations or NGOs that contract with local governments to provide temporary shelter for migrants released by border agents as legal asylum seekers. Lamb falsely claimed migrants were given $5,000 Visa cards, cell phones and free plane tickets in a December video posted to X, formerly Twitter.

Lamb did not respond to the Star’s request for comment about whether he stands by his comments in the video, which has more than 226,000 views but has been repeatedly debunked.

Rafael Barceló Durazo, Consul of Mexico in Tucson, said the Mexican government is “very concerned” about how rising anti-immigrant sentiment endangers people of Mexican descent in the U.S.

In late November, Rick Saling of the Tucson Samaritans watches the arrival of his fellow volunteers, who had driven to the top of a steep border-road hill to try to get cell phone reception at the remote crossing point, about 15 miles east of Sásabe, Arizona.

He pointed to the 2019 mass shooting at a Walmart in El Paso, Texas, which killed 23 and injured 22 others. The shooter’s manifesto decried an “invasion” of Mexicans, and he told police he was targeting Mexicans.

“Words matter. The violent discourse on migrants matters,” Barceló Durazo said. “That is going to make life not only of migrants, but also of people of Mexican origin, much more dangerous in the United States and we are concerned because of that.”

Education on immigration law and history is needed, as uninformed news consumers are easier to manipulate, Barceló Durazo said.

“The merchants of fear are going to profit from people that don’t want to take some time and effort to understand the migratory process,” he said. “It’s simpler, and lucrative, for some people to dehumanize migrants. It takes time and effort to understand what is going on in migration, and it’s easy to succumb to simpler narratives that are misleading.”

He pointed out that today, many “economic migrants” are Americans moving from the U.S. to Mexico to take advantage of the low cost of living. Parts of Mexico City have been transformed by legions of “digital nomads” who’ve arrived since the pandemic.

“They are making that decision for economic reasons,” he said. “It’s a natural thing.”

Casa Alitas targeted

Workers at Casa Alitas shelter in Tucson and its partners in Nogales were recently targeted by right-wing activist James O’Keefe, who falsely claimed in a Jan. 17 video, filmed in front of Casa Alitas’ Drexel Center, that he was uncovering a “secret” facility that “none of the American people knew about until now.”

O’Keefe’s video — which Elon Musk amplified by commenting underneath it twice — has been viewed nearly 3 million times on X.

Another right-wing media group, Oreo Express, later filmed more videos there, posting them to 50,000 YouTube followers. In the clips, the group falsely asserts the facility is a “human trafficking center” and accuses a Tucson police officer, who asks them to stay off private property, of “refusing to investigate human trafficking.”

Jeannette Juarez, far right, a site coordinator at the Casa Alitas Drexel Center, gives a migrant family a bag to place their few belongings in before they head off to the Tucson International Airport on Sept. 26.

In reality, the supposedly “secret” site has been in the news for months, throughout Pima County’s very public process of purchasing it, said Grijalva, chair of the Pima County Board of Supervisors.

Without the work of Casa Alitas, in close coordination with Border Patrol and the county, Tucson and smaller border communities would be facing large numbers of unsheltered migrants on the streets, county officials say.

The online attacks are another example of propagandists falsely attributing nefarious motives to easily explainable events, Grijalva said.

“We’re not being secretive about it. We’ve had elected officials, community groups, volunteers walk through Casa Alitas,” Grijalva said. “That is the frustration and the fear, when you have these people that have ulterior motives make it seem as if Pima County or the government is trying to do something sneaky.”

Aid workers targeted

Along the border, east of the Sásabe port of entry, volunteers have been providing water, food and blankets to asylum seekers whom human smugglers have dropped off in the remote area, only accessible over rough, hilly terrain.

In December, No More Deaths put up tents and built a rugged kitchen in the remote location, to store supplies and to provide some shelter for migrants, who faced life-threatening conditions while waiting overnight in freezing temperatures and heavy rain for border agents to arrive, volunteers said.

Right-wing activists have targeted the camp in recent weeks. In another January video from Oreo Express, streamed live to thousands of followers, the live-streamers taunt the volunteers and falsely claim they’re terrorists, pedophiles and child traffickers — as well as Communists, Marxists and “mentally ill.” They also accuse Border Patrol agents of being “in bed with” aid workers.

In some videos, streamers express outrage about openings in the border wall in Arizona, attributing the gaps to the Biden administration’s so-called “open borders.”

In reality, gaps in the border wall were left open by hurried construction crews during the Trump administration and are now being closed under the current administration, said John Modlin, chief of Border Patrol’s Tucson Sector.

Wall construction under Trump was focused on covering a lot of ground as quickly as possible, Modlin said.

“When there were challenging areas, those areas were skipped over to go further and get more of the border wall constructed,” he said.

Now remediation of those gaps, many of which require time-consuming erosion control, is underway, he said.

“Some people see some of that, they see the construction equipment and maybe think they’re removing fence, instead of putting it in there. But that is the closing of those gaps,” he said.

Human smugglers in Mexico also routinely cut through the wall’s 30-foot bollards with power tools. And at various points along the wall, floodgates are installed as a necessary means of disaster prevention: During monsoon season, heavy rains and debris would damage or topple the border wall, if it weren’t for gates that allow powerful floodwaters to flow southward.

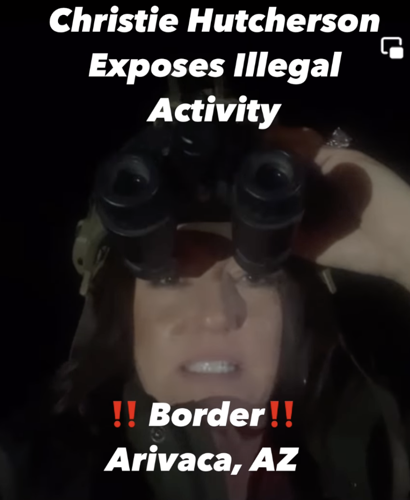

Christie Hutcherson, founder of Women Fighting for America and a collaborator with Arizona militia groups, has also been targeting Arizona aid workers and migrant-aid groups. In a Jan. 30 nighttime video that Hutcherson posted online from Arivaca, Arizona, she’s wearing night-vision goggles and a helmet, claiming to be exposing “illegal activity within NGOs.”

In a still image from a Jan. 30 video of Christie Hutcherson, founder of Women Fighting for America, in Arivaca, Arizona, Hutcherson wears a helmet and night-vision googles. According to the Western States Center, "Hutcherson has alleged children are being trafficked throughout the U.S. with the help of CBP, the Biden administration and other government agencies. During her 2021 border operations, she frequently intercepted and detained unaccompanied migrant children."

In a separate Jan. 31 video — filmed by a local aid worker and shared with the Star — Hutcherson aggressively questions Tucson Samaritan volunteers and migrants as they wait for border agents to arrive at the border wall, east of Sásabe.

Hutcherson, who spoke at the pro-Trump rally on the eve of the Jan. 6 riots in D.C., accuses one volunteer both of being responsible for migrant deaths in the desert and of “aiding and abetting” terrorists and traffickers. While filming on her phone, Hutcherson asks the migrants, who sit silently, at least six times within five minutes, “What Middle Eastern country are you from?” and “What Arabic country are you from?”

According to the Western States Center, “Hutcherson has alleged children are being trafficked throughout the U.S. with the help of CBP, the Biden administration and other government agencies. During her 2021 border operations, she frequently intercepted and detained unaccompanied migrant children.”

In a statement, U.S. Customs and Border Protection, the agency that oversees Border Patrol, said that forcibly detaining migrants “can also be viewed as a criminal offense.”

“CBP encourages individuals — from hikers, hunters, humanitarians to citizen groups — to notify us of their planned activities in remote areas or locations where illegal cross-border activity occurs in southern Arizona,” the statement said. “CBP does not endorse or support any private group or organization from taking matters into their own hands as it could have disastrous personal and public safety consequences.”

In the Jan. 31 video, Hutcherson also repeatedly claims she’s “working with local law enforcement.”

Both the Pima County and Santa Cruz County Sheriff’s Departments said they are not working with Hutcherson. A CBP spokesman said Border Patrol does not coordinate with any groups or individuals at the border.

Hutcherson did not respond to the Star’s attempts to reach her through her website’s contact page and email address.

Santa Cruz County Sheriff David Hathaway said two years ago, Hutcherson contacted his office and he agreed to let her go on a ride-along with one of his officers, who happened to be Hispanic.

“She was very offended. She said she couldn’t work with any Hispanics, they were all corrupt. She started saying our department was corrupt and controlled by the cartels,” he said.

“I tried to initially treat her like I would anybody else, giving her the benefit of the doubt,” he said. But Hathaway said he came to realize “she’s not trying to help anybody or do anything other than inflate herself and try to get followers.”

Vigilantes and right-wing activists who show up in border communities are often upset by the close relationship between Nogales, Arizona and Nogales, Sonora, said Hathaway, who said his family has been there for five generations.

“Those people don’t really know the border. They didn’t grow up here like I did,” he said. “My county has the largest ports of entry with Mexico in Arizona. It’s a symbiotic relationship. Our retail merchants, our hospitality industry depend on that relationship with Mexico.”

Stop the Hate Collective

Tucson human rights advocates want to counter hate with facts.

In 2020, advocacy groups formed the “Stop the Hate Collective,” during another election-year surge in hate speech directed at migrants and other marginalized groups, said collective co-founder Isabel García, an immigrant-rights activist and attorney with Coalición de Derechos Humanos.

The group aims to counter hate speech, particularly that comes from politicians with large platforms, and encourage voters to support politicians who shun such rhetoric.

Hundreds have signed the collective’s 11-point pledge, including goals like speaking out against racism and bigotry, centering human rights in policy decisions and rejecting efforts to return migrants and refugees to dangerous situations.

“Let’s face it: There’s a lot of hatred, but it goes on top of a lot of ignorance,” García said. “In our country, we don’t teach the history of immigration. ... Without education, and with ignorance and lies, comes violence.”

She pointed to Nogales-area rancher George Alan Kelly, who is facing a second-degree murder charge and an aggravated assault charge for fatally shooting a Mexican migrant on his property last year.

“That is a result of hate speech and hate thinking,” she said. “We’re seeing the atmosphere is toxic with this kind of hatred, so we’re trying to counter that with facts. We’re trying to tell people to look at how communities that have large numbers of immigrants have less crime. Border towns are safer than other places.”

Local aid workers say while the presence of angry, armed extremists is worrisome, they won’t be deterred from their work.

“We don’t give them any energy. While they’re out playing soldier, we’re in the desert saving lives every day,” said Cantillo of Humane Borders. “It only strengthens our resolve to deliver water.”

Tucson Samaritan Kocourek agreed, adding that she’s also provided water to vigilantes who were stranded on the side of the road in the borderlands.

“I don’t care who you are. If you need help, I will help you,” she said. “I was not raised to judge. I was raised that only God can judge.”