A Tucson physical therapist is facing deportation to Laos — the country he fled with his family as a child, in the 1970s — due to a non-violent crime he committed as a teenager, 35 years ago.

Vone Phrommany, 53, said he was arrested by plain-clothes immigration agents on July 28, after leaving a patient’s home north of Tucson. He’s now detained in Eloy Detention Center, while U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement seeks travel documents from the Lao government to facilitate his return.

Since fleeing the communist regime in Laos, and later receiving legal permanent residency in the U.S., Vone said his parents and siblings were able to become U.S. citizens. But Vone was unable to get citizenship because of what he calls a “stupid, naive” mistake.

At age 18, Vone was caught selling $140 worth of LSD and faced deportation for the crime, which is considered an aggravated felony since LSD is a controlled substance, Vone told the Arizona Daily Star, speaking by phone from the Eloy Detention Center. He pleaded guilty, allowing him to participate in a work-release program, he said.

Phrommany

Since Laos wasn’t accepting deportations at the time, Vone was able to stay in the U.S. after serving his sentence, despite the deportation order.

In the decades since, Vone put himself through college, got a master’s degree and then a doctorate in physical therapy, while maintaining a clean record, work authorization and complying with ICE’s requirement for routine check-ins, he said. He has worked as a physical therapist for 23 years, 18 of them in Tucson.

“I truly regret what I did when I was a kid. It changed my life, and that is not who I am,” Vone told the Star. “I just want to get my life back and take care of my clients.”

Vone’s last ICE check-in went smoothly in January, but he knew he would be vulnerable to the Trump administration’s mass deportation campaign. Though fearful, Vone said he didn’t consider stopping work or going into hiding because, “Where was I going to go? And plus, I love my job.”

He also felt ashamed about his past, he said. “I didn’t want people to know about my situation.”

Vone’s family is struggling to find legal representation and have started a petition on Change.org advocating for his release, which has more than 3,500 signatures.

But attorneys have told the family, with the existing deportation order, it’s unlikely Vone can avoid deportation if the U.S. government is committed to it.

Legally, someone with a conviction like Vone’s can be removed from the U.S., but under previous administrations, “DHS was more apt to exercise discretion favorably, if persons maintained a record of positive conduct and stayed off the radar,” said immigration attorney Luis Campos. He is not representing Vone, but has consulted with his family.

“This particular government makes that irrelevant,” Campos said. “This government has taken the position, ‘We’re gonna bring these cases back from dormancy. If you have a prior removal order, we are within our legal rights to remove you. Your rehabilitation and good conduct do not matter.’ It’s mostly a matter of discretion.”

ICE has not responded to the Star’s requests for comment on Vone’s arrest.

Vone’s home-health clients adore him, and his family, as well as his “work family” in Tucson, are devastated by his arrest, his Phoenix-based sister Sace Phrommany Rydberg told the Star. Dozens of his patients and coworkers have reached out to express their support and concern, she said.

“They want to deport a vital health care (provider) that’s needed in our community,” Sace said. “He’s making a difference for our elder population. I just don’t understand why they would be doing this. They should be concentrating on the worst of the worst, rapists and murderers. I don’t understand why they can’t take it case by case.”

Sace Phrommany Rydberg, right, is pictured here with her older brother Vone Phrommany in 2019. They are two of eight siblings in the Phrommany family.

Work ethic instilled early

As refugees in South Dakota, the Phrommany family was tight-knit and intent on giving back to the country that gave them refuge, after the communist movement gained power in Laos in the 1970s, supported by North Vietnam, Sace said.

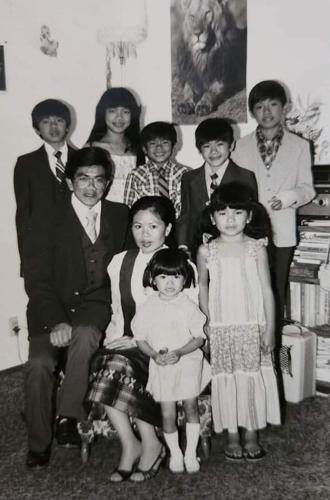

The Phrommany family is pictured in 1982, in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, two years after Lutheran Social Services sponsored the family as refugees. Vone Phrommany, currently detained at Eloy Detention Center, is in the back row, second from right, and his sister Sace is the front row at right. The family fled the communist regime in their home country of Laos in 1978.

Their father, Kongsy, had been an Army lieutenant in Laos, assisting the U.S. military during the Vietnam War. He was imprisoned by the communist regime when it took over in 1975. Tortured and starved while imprisoned, he was eventually freed to get medical care, and so he could join the communist regime, she said.

That’s when their family fled, escaping across the Mekong River at night to reach a Thai refugee camp in 1978, Sace said. They eventually made their way to Sioux Falls, South Dakota in 1980, when Lutheran Social Services sponsored the family as refugees. Vone had just turned 8 when they arrived in the U.S.

“We all knew when we got to America it was going to be hard. We didn’t want any handouts,” said Sace, who was 5 at the time and later learned the details of their journey from her mother.

Her father worked two or three jobs at a time, and all the children worked from a young age delivering newspapers in Sioux Falls, venturing into the snow without proper jackets and coats, she said. Their mother, Khemma, “was a mom to everyone,” and cooked traditional Lao food to share with families in the community, Sace said.

Vone was his father’s “right-hand man,” acting as his translator from an early age, she said. He excelled both in sports and academically, and his father proudly saved all his trophies and awards, Sace said.

“My parents always told us, ‘You have to be smart. Be a lawyer, or a doctor,’” she said. “All of us had that drive to do better. We always tried to achieve and prove we could do it.”

As the family struggled financially when the kids were young, she said, “We all had that drive to acquire money.”

Vone struggled in high school as he was relentlessly bullied by neighborhood kids, due to his race and smaller statute, Sace said. It was around that time he fell in with a bad crowd and was introduced to the idea of selling the hallucinogenic drug for spending money, his sister said. Vone said he sold a small amount of LSD on two occasions, before making the $140 sale to an undercover police officer, soon after his 18th birthday.

The thought of Vone getting deported is almost too much to bear, Sace said. Both of their parents have died from cancer, with their mother passing away just last year. Vone was his mom’s part-time caretaker after his father died, Sace said.

“He made one mistake as a teenager that’s haunting him,” she said. “I don’t understand how they’re categorizing him as the worst of the worst. ... That one mistake is ruining his life right now.”

He’s passed numerous drug tests and background checks over the years, in order to be able to work as a home-health provider, she said.

“There’s no way he could have gotten his job if he was a repeat offender,” Sace said.

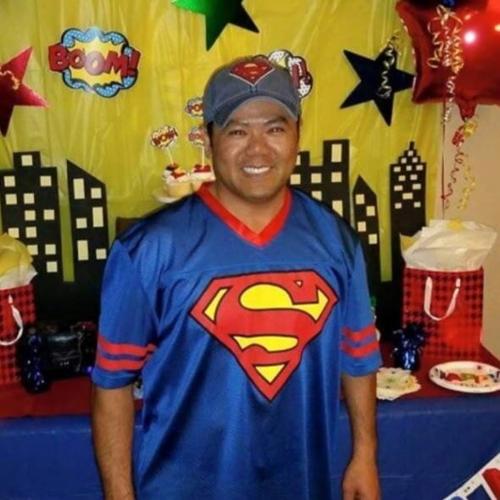

Friends and family have a nickname for Vone Phrommany: "Super Vone," due to his tendency to go above and beyond in helping others, said his sister Sace Phrommany Rydberg.

‘One of a kind’

Co-worker Dolly Scott, a single mom, said she’s developed a deep friendship with Vone since they met through work eight years ago.

“He is the best friend that anybody could want,” she said tearfully. “He has helped me in countless ways, me and my kids. He would literally take the shirt off his back if you needed it.”

Vone is just as generous with his home-health patients, Scott said. He put up Christmas lights for one Tucson family when their injured father was unable to do it that year, and he routinely buys items for his patients out of his own pocket, including an air conditioner for a family who couldn’t afford it, Scott said.

“He is one of a kind. My family is just torn apart with this, because he is part of our family,” she said.

Of Vone’s deportation order, Scott said, “I can see (the logic) if he’d hurt somebody, but he didn’t hurt anybody. ... He did everything he was supposed to do to better himself.”

Oro Valley resident Bette Taylor, 85, said Vone was a “magician” when working with her late husband Richard, who struggled to walk after a difficult bout of COVID in 2020 and again two years later, after a hospitalization. She credits Vone with giving her more quality time with her husband before his death.

“My husband was hard of hearing, and he was lazy,” Taylor said. “But Vone was a magician. He got Richard up and off of his butt and walking down the hall and stepping over the cones. ... He is just an amazing human being. A caring, sensitive human being.”

The idea that Vone’s teenage mistake could outweigh a lifetime of service is “outrageous,” Taylor said, recalling she once stole a bra from Hecht’s department store when she was a teen, although she later felt guilty and returned it.

“Because he sold drugs when he was a few days over 18, they count that the same as rape, murder, grand larceny? It’s not right,” Taylor said. “The man has dedicated his adult life to taking care of others, to giving people the best quality of life. ... It’s just a travesty that this has happened.”

Laos historically has rarely accepted deportations from the U.S. and the country doesn’t have a formal repatriation agreement with the U.S., according to the Asian Law Caucus, a legal and civil rights organization for Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders.

But in response to pressure from the U.S., which imposed a partial travel ban and visa restrictions on Laos in June, the Lao government has been issuing travel documents to facilitate deportations, the group said.

Sace said she’s concerned that since Vone was born at home, and there’s no record of his birth in Laos, he might be considered “stateless” and could be deported to an unfamiliar country where he could be in danger.

“I’m afraid they’re going to send him to a third-world country that would be extremely violent, and conditions won’t be good for him,” she said.

The family also didn’t have time to deal with the transfer of Vone’s assets — including his car and the home he owns in Marana — before he was detained by ICE. ICE has been slow to allow Vone to sign documents his family sent to Eloy, including his car title, so his siblings can manage those assets, Sace said.

Speaking by phone from Eloy, Vone said conditions at the detention center have been “okay,” although there’s no privacy when using the bathroom and “the food could be better.”

Vone said he’s met both detainees with serious, violent convictions on their record, and many without any criminal record. He’s provided counsel to some whose medical conditions had been neglected, including a man whose gout left him unable to walk and a cell mate with vertigo from a head injury, helping both to get back on their feet, he said.

“I see that they’re hurting and I ask them, ‘What’s the problem?’” he said. “I like to be helpful.”

It’s hard to imagine returning to Laos, where he hasn’t been since he was 6 years old, Vone said.

“I just wouldn’t know where to begin,” he said. “I can’t read or write the language, I barely speak it. It would be a culture shock, just like when we came here in 1980.”

Vone said he’s grateful for the support of his friends, family and patients, and he wants to assure them he’s “in good spirits” and holding out hope for a review of his case.

“I love all the support,” he said. “I miss working. I miss my clients. I miss my work family and my real family. I miss being out there.”

Tucson physical therapist Vone Phrommany is pictured in 2025 with two of his nieces, who are also his goddaughters.