On a rocky slope at the western edge of Avra Valley, recent monsoon moisture has painted the desert vibrant green.

Native shrubs and grasses sprout from once-bare ground amid a scattered forest of leafed-out ocotillo stems, verdant palo verdes and young ironwood trees on the cusp of adolescent growth spurts.

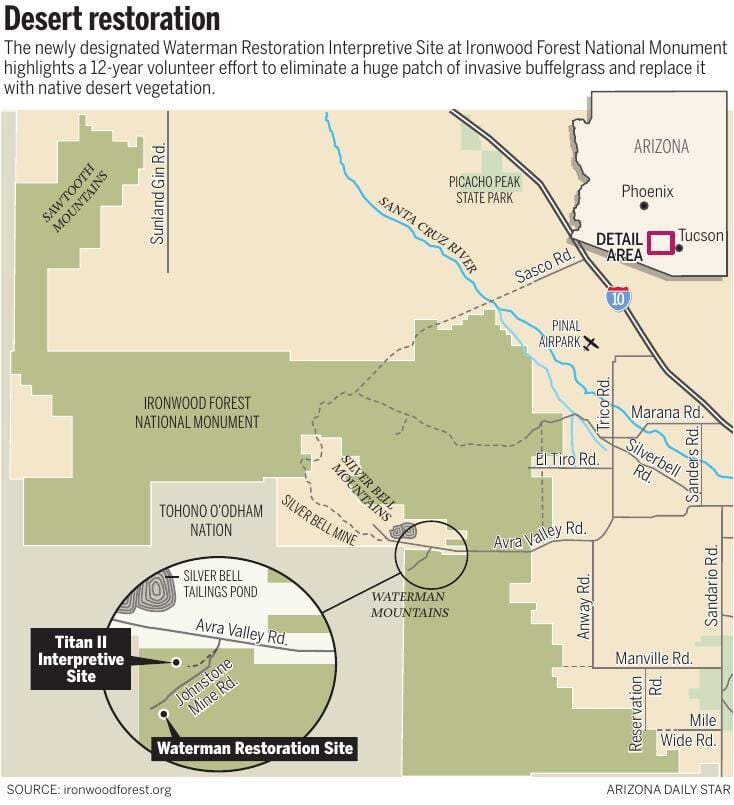

You can still see the outline of an airstrip and other hints from the industrial past, but the invasive weeds are gone and the desert is gradually reclaiming this corner of Ironwood Forest National Monument.

Two decades ago, these 18 acres off of Avra Valley Road near the Silver Bell Mine were home to what some conservationists called “the mother of all buffelgrass patches.”

Today the land is a rehabilitation success story that is about to get some national recognition.

Sometime early next month, signs will go up directing visitors to the newly designated Waterman Restoration Interpretive Site and demonstration garden.

The Bureau of Land Management will officially unveil the educational attraction during an event planned for Oct. 22.

And all it took was a sustained, 12-year campaign involving hundreds of volunteers from numerous nonprofit groups, who spent more than 7,000 hours toiling away at the site with BLM support but no real funding.

“It’s an affirmation of a lot of effort,” said John Scheuring, who headed up the project as conservation chair of Arizona Native Plant Society.

On a recent Tuesday morning, Scheuring and fellow native plant society member Dennis LeBlond offered a tour of their on-going experiment in desert recovery.

Scheuring called it the largest saguaro-palo verde upland landscape restoration of its kind anywhere in the Sonoran Desert.

“We’re eager for (our) lessons to be shared as an example and to give hope to others that this can be repeated elsewhere,” he said.

A sea of grass

For almost 20 years, this swath of federal land on the northern flank of the Waterman Mountains served as the base of operations for a nearby materials pit.

Scheuring said the owner of the mining claim lived at the site from the late 1970s through the late 1990s, when the BLM evicted him out of concern for an endangered species of cactus in the area.

By the time the man left, he’d carved up the land with heavy equipment, clearing away desert plants to build roads, pads for his office and home, a mine waste pile and a landing strip more than half a mile long for his collection of small airplanes.

“He loved bulldozers,” Scheuring said.

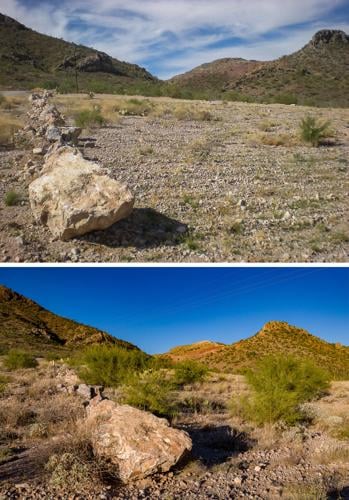

A rock dam was built to slow the flow of rainwater and to water desert plants at the 18-acre Waterman Restoration Interpretive Site and demonstration garden northwest of Tucson.

The BLM ordered the man to clean the place up and revegetate it before he cleared out, but within a few years of his departure the land was choked with one of Southern Arizona’s most problematic pests.

“It had become a monoculture of buffelgrass. I mean, it was like a golf course,” Scheuring said.

The fast-growing perennial from Africa and Asia was first introduced to Arizona in the 1930s as hardy ground cover and forage for livestock. It has since exploded into a major threat to the desert ecosystem, where it spreads even in dry years to crowd out native plants and fuel once-rare wildfires that are deadly to saguaros, palo verdes and other plants poorly suited to survive the flames.

Scheuring credits the Grand Canyon chapter of the Sierra Club and its long-time director, Sandy Bahr, for first taking on the buffelgrass problem in the Watermans in 2005.

“By golly, Sandy organized volunteers out of Phoenix to come down, and she coordinated with BLM to dig this stuff,” he said.

Bahr said she first learned about the site from one of her group’s Tucson members. She was immediately struck by the scale of the infestation.

“It was really a sea of buffelgrass, and it was moving out into the washes,” Bahr said. “It was pretty outrageous.”

Scheuring joined the Sierra Club’s effort in the Watermans in 2006, after retiring early from a major agri-chemical company, but he said he quickly discovered the limitations of yanking the stuff out by hand.

“It was kind of hopeless, you know? You’d dig up plants, and six months later, they’d all be back,” he said.

So Scheuring got an herbicide applicator’s license from the state, and started recruiting volunteers to spray the mother of all patches into submission once and for all.

They fanned out with backpack sprayers and walked the site from top to bottom three times a week from early August into October, spot-spraying the bright green invaders.

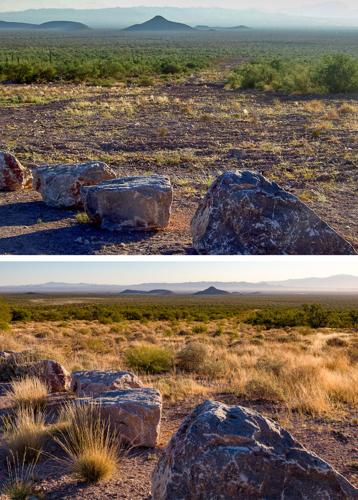

Photos taken from the same spot at Ironwood Forest National Monument on June 29, 2010, top, and Oct. 15, 2021, show the regrowth of native plants at what is now known as the Waterman Restoration Interpretive Site.

“We laid down an enormous amount of herbicide the first year, like 234 gallons,” Scheuring said, but the amount of chemicals decreased dramatically after that.

By the second year, they used about 74 gallons of glyphosate to treat the same area. By year four, it was down to 10 gallons. Now it ranges from three to five gallons a year, depending on conditions on the ground, he said.

Water retention

Getting rid of buffelgrass turned out to be the easy part. The real challenge was turning the property back into the sort of place where native plants might actually grow.

“One thing we know about the desert is anytime you allow bulldozers or ATVs to tear it up, it doesn’t just come back,” Bahr said. “You have to really look at investing in” its recovery.

Scheuring said the Arizona Native Plant Society eventually approached the BLM with a plan: If the bureau would reshape the contours of the site, he and his volunteers would do the rest.

So in June of 2010, the agency brought in some large earth-moving machines and people qualified to operate them. They ripped up areas that had been bulldozed and compacted, erased roads, and moved boulders to line the edges of the property in hopes of keeping ATVs and dirt bikes from riding around the site.

The remnants of an old airstrip can still be seen in photos taken from the same spot at Ironwood Forest National Monument on June 29, 2010, top, and Oct. 15, 2021, but the successful regrowth of native plants has led to the area being federally designated as the Waterman Restoration Interpretive Site.

Then Scheuring and company set to work reestablishing native plants and reengineering the landscape to make better use of what little moisture nature provides.

Scheuring said the first thing they planted were the “woodies”: Ironwood, whitethorn acacia and foothills palo verde trees, all grown from seeds collected just down the hill, along Avra Valley Road.

The entire 18 acres was planted by hand. For about six weeks, Scheuring said, helpers walked the length of each furrow left by BLM’s ripping machines, stopping every few feet to drop three seed pods and kick some dirt over them before moving on.

“Thank God we had a lot of BLM interns that year, and we had a lot of volunteers,” Scheuring said. “There were even interns who came on weekends. It was amazing.”

And the work didn’t stop there. For years afterward, the restoration crew would return to plant more seeds in areas where the first few batches of trees didn’t take.

As a result, more than 2,000 young trees now grow at the site, and every one of them has “come up from seed and has not received a drop of water except for rainfall,” Scheuring said.

Fellow Arizona Native Plant Society member Dennis LeBlond was the mastermind behind the crucial water-harvesting improvements that made everything possible.

Tapping into techniques used a thousand years ago by Indigenous people in the area, he led the construction of more than 150 small dams, each no more than one layer of rock high, to keep rainwater from rushing off the property and carrying the topsoil with it.

LeBlond and company also used rocks to stabilize or block countless erosion channels, and they recruited a BLM backhoe operator to scoop out hundreds of shallow “water catchment dimples” to loosen the soil and foster puddles in areas where the ground had been compacted and covered in gravel.

Finally, they gathered truckloads of desert tree branches from a major roadside pruning project in Avra Valley and hauled them up the hill to use as a kind of mulch.

Photos taken from the same spot at Ironwood Forest National Monument on June 29, 2010, top, and Oct. 15, 2021, show the regrowth of foothills palo verde trees and other native plants at what is now known as the Waterman Restoration Interpretive Site.

The individual branches were scattered across the property to shade the bare ground, trap moisture and create small incubators for native grasses and other plants. And as the dead branches decomposed, they added organic material to the soil to feed future plant growth.

“We organized what we called drag parties for people to drag the branches into the site,” Scheuring said.

The result is a “living laboratory of what can be done” to restore disturbed desert areas by stabilizing the soil and restoring hydrologic function, said BLM natural resources specialist Theresa Condo.

“It’s not just about planting things, it’s about turning (the land) back into a functioning system,” said Condo, whose Tucson field office manages the 129,000-acre national monument.

Volunteer labor

When it’s officially unveiled next month, the Waterman Restoration Interpretive Site will feature four informational panels explaining the effort, alongside a small collection of representative plants.

“We always wanted to put up a demonstration garden so that we could have the public, even passively, come by and take a look at the default plants that are out here,” Scheuring explained.

LeBlond planted the selection of native trees, shrubs and grasses himself starting in 2017.

“Most of these plants I grew from seed I collected from around here. I came out here every weekend to water (them) for years,” he said.

He doesn’t do that anymore. Now that the plants are established, they don’t need his help.

The garden is built on top of a layer cake of dirt left over by the mine claim holder and limestone chunks donated by the still-active Pioneer mine nearby, forming a water-trapping island alongside the road that LeBlond and Scheuring call the “100-ton sponge.”

The hand-watering that LeBlond did to get the garden established was “the only water amendment ever done on this site,” Scheuring said with obvious pride.

Virtually everything else that now grows on the property sprouted there on its own — either from seeds that were already in the ground or were carried onto the site by wind or wildlife.

Saguaros are the lone exception.

So far, the restoration crew has planted more than 30 of the young cactuses underneath some of the nurse trees that have sprouted there.

“The first one I planted I am certain was eaten by (bighorn) sheep,” LeBlond said.

They now have an agreement with the Tucson Cactus and Succulent Society to get some of the small saguaros that the group rescues from construction sites across Southern Arizona.

A large and diverse group of volunteers assisted with the restoration effort over the years. There have been 14 different Eagle Scout projects at the site, and the native plant society hosts a work day there each December that consistently draws 45 to 50 people.

The Friends of Ironwood Forest has also supplied “an awful lot of labor” over the years, Scheuring said, as has the environmental science club at the University of Arizona and youth groups from the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum.

Thanks to all that help, the site has finally reached the point where all it requires is stewardship and some annual maintenance.

In other words, Scheuring said, the time has come to show it off a little.

“We want to turn it into an educational thing, because I think there are too many elements here that might get lost,” he said. “The take-home message is: You can’t do things fast, and you can’t throw a lot of money at it. You’ve got to spend the time, and water is the key.”

For Star subscribers: Everyone has their own way of keeping cool during the hot summer months in Tucson. Scientist Chad Greene studies the ice sheets of Antarctica.

An American pilot killed on D-Day was finally laid to rest in France, after a multi-generational effort by family members in Tucson and elsewhere.