If you tool around downtown Tucson today, you can easily tell which buildings are historic and which are new.

The old ones are built with brick.

The new ones aren’t.

The worst newer buildings are of “stick-and-stucco” construction, the cheapest that money can buy. You can see a few of those around the city center, and more are planned.

But even in better new buildings, you won’t see brick.

Learning why led me to a bigger point. We really don’t have strong design guidelines for new downtown buildings. That’s important today because the building boom continues downtown, and those new structures, whether they’re ugly or beautiful, will be around for decades.

But back to brick — a beautiful material that became dominant in new construction after the railroad arrived in Tucson in 1880. Before that, adobe and other local mud bricks predominated, but the railroad brought in new red-clay bricks from places as far away as Chicago.

“A hundred years ago, downtown Tucson was all being built with brick,” architect Bob Vint told me. “Brick was the predominant material.”

“It’s a great material because it’s your structure, your finish, and your enclosure all in one.”

That lasted until maybe World War II, said Jonathan Mabry, the city’s historic preservation officer. Then other materials, like concrete and new methods of construction came into vogue. Some covered up their brick exteriors to make their buildings look more modern.

”Building owners always want to look like they’re keeping up with the times,” Mabry said.

More important, though, building with brick became too expensive. It’s the labor of putting up brick and mortar, brick and mortar, not so much the materials, that make it so expensive.

It’s a fraction of the cost to put up a wood frame and stucco building. Even putting up a veneer of brick is costly. So most developers and builders don’t bother with the extra cost, even if it would make a new building fit in better with the old downtown buildings.

And some architects prefer not to try to fit in. I spoke Friday with Miguel Fuentevilla and Sonya Sotinsky, the principals at Fors Architecture, the architects for the new AC Marriott downtown who have also worked on older buildings downtown.

”Our approach is very in line with historical preservation thought and theory,” Sotinsky said. “There should be a clear differentiation between old and new. You should not be trying to imitate the old, because that diminishes the old.”

Rather than imitate the old, their ground floor tries to invite people into the historic neighborhood through the use of glass.

”The top is almost like the tortoise shell. The bottom is more open,” Fuentevilla said.

Their way of thinking — trying to distinguish the new from the old — was new to me.

Instinctively, I want new buildings in an old neighborhood to fit in, somehow. That’s one of the reasons I’ve been disappointed to see the new Holualoa Cos. rowhouses on South Stone Avenue, just south of the cathedral. These stick-and-stucco constructions look to me like they could be anywhere, up on East River Road or out on East Speedway.

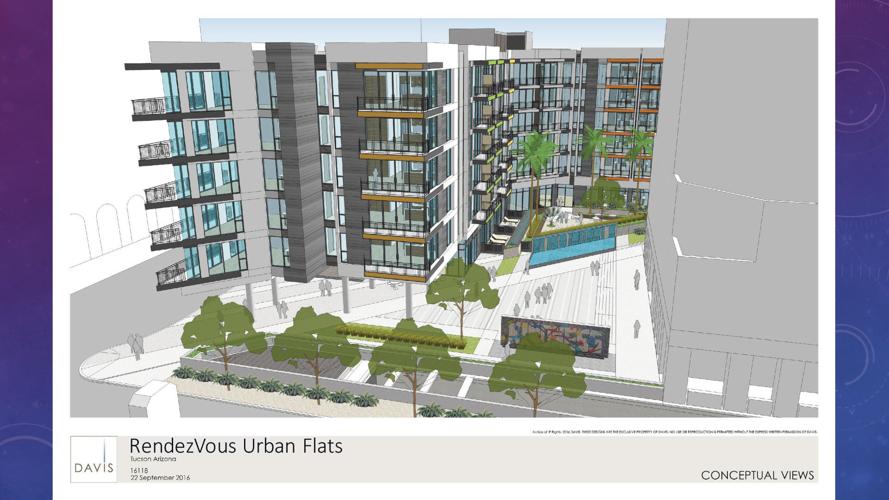

The same could be true of a pair of planned apartment complexes downtown.

Aerie Development’s project at the corner of Stone and Broadway has a big challenge of fitting its new apartments into what is now a densely built space and not building something that looks like it belongs on South Pantano Parkway.

HSL Properties has a similar challenge with its apartment complex that will replace the La Placita Village office complex at Church and Broadway.

Of course, many of the decisions come back to money — not just how much it costs to construct a new building but how quickly the developers want or need a return on their investment.

“The driving force for any building is to maximize profits for investors,” Vint said.

“When you have a high-profit goal, you have to build with frame.”

Even thin brick veneer, which doesn’t require the laborious mortaring process, costs about $10 per square foot to about $1.50 for stucco, Vint said.

Brick is part of the plan for at least one new downtown project. The Ronstadt, Peach Properties’ project that will replace the Ronstadt Transit Center if it wins final approvals, will use the existing brickwork that surrounds the bus station in its streetscape or first-floor design, Peach owner Ron Schwabe said.

Those bricks were recycled from the demolished Ronstadt Hardware and Owl Drug Store on that site.

Above the ground floor, the design is much different. A series of low, layered towers with bright-colored details rise over plazas below.

It is a striking design, with potential to look great or out of place in the heart of downtown.

Mabry noted there are downtown design guidelines, but they could be made tighter if the City Council wishes.

New structures, he said, “need to be designed to fit with the character of our existing historic buildings. New buildings should not mimic historic buildings, but they should complement them.”

Now that’s what I’m wishing for as the parking lots and vacant spaces are filled downtown.

Not more brick buildings, which I understand are not coming back, but structures that at least complement the old brick downtown.