A mesquite bosque and 1,500 other desert plants will adorn a new 40-acre city of Tucson site on the southeast side that will double as a desert park and an effluent recharge and storage facility.

When the South Houghton Area Recharge Project opens this fall on East Drexel Road just west of South Houghton Road on Tucson’s southeast side, Tucson Water officials plan to start recharging 4,000 acre-feet of reclaimed water there annually into three basins. An acre-foot is enough to supply four Tucson homes with enough water for a year.

The basins will be surrounded by more than 1,500 desert plants, placed there with an eye toward creating irrigated wildlife habitat lusher than the natural desert. The site will be tailored to draw birds and bird-watchers, in the fashion of the Sweetwater Wetlands the city runs on the northwest side.

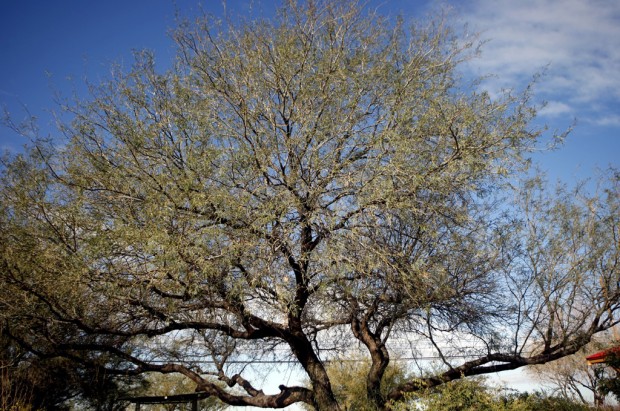

But it will be a smaller and more typically desert version, as opposed to the wetlands of cattails, bulrushes and cottonwood and willow trees planted at Sweetwater, said James MacAdam, the utility’s conservation and public information supervisor. Besides more than 230 mesquite trees, the new park will have 131 palo verde trees, 88 whitethorn acacia trees, 48 desert willows, 220 desert honeysuckle shrubs, 81 desert hackberries, 62 barrel cacti, 29 saguaros and 172 creosote bushes.

The new, $8 million Houghton recharge project will include three basins and cover 40 acres. Sweetwater has 40 acres holding 11 recharge basins and 22 additional acres of wetlands.

The new park also will havecontain ramadas, benches, picnic tables and raised viewing platforms looking out onto the water. Decomposed granite pedestrian paths and multiuse asphalt paths will allowhelp walkers and cyclists to enjoy the area.

The city could double the site’s effluent storage capacity latern the future, should continued population growth warrant it , MacAdam said. The reclaimed water is effluent that gets an additional layer of treatment after it leaves Pima County’s sewage treatment plants.

While Tucson Water used to say it would someday need to treat some of this reclaimed water to drinking quality, it since backed off that idea in the near future while not ruling it out for the long term. Pumping this water from the ground is “decades away,” MacAdam said.

The Houghton project, known as SHARP for short, has been under construction since January 2019 and in the planning stages for nearly a decade. It hasn’t been a totally smooth process, since the Pima County Regional Wastewater Reclamation Department pulled out as a joint partner a few years ago, citing what its officials called an excessive construction price tab.

An early rationale for the project has also disappeared. It was once planned so the city and county could get far more credits for recharging the reclaimed water than if the effluent kept being discharged into the Santa Cruz River from the county’s Aqua Nueva sewage treatment plant. That’s where the effluent has gone for decades. The credits allow the city to pump an equal amount of groundwater elsewhere.

But a change in state law in 2019 now allows owners of effluent rights to gain the same amount of credits whether they take it out of rivers or not. Tucson Water officials say they still have other valid, water-related reasons for recharging at the South Houghton site.

But Eric Holler, a retired U.S. Bureau of Reclamation official who has worked on other recharge projects, is skeptical of that, although he has no problem developing the site as a park.

Recharge for testing will start this summer at the Houghton Road site. It begins at full scale in the fall when more reclaimed water is available. During the summer, much of the city’s reclaimed supply goes to golf courses and parks that don’t need it in cooler weather.

But even in cooler months, visitors won’t be guaranteed a steady view of water. That’s because the rate that water infiltrates into the aquifer there have been found to be very high there, meaning the basins may not stay full for very long, MacAdam said.

It will be the utility’s sixth recharge facility. Two in the Avra Valley southwest of Tucson and one along Pima Mine Road south of the city recharge Central Arizona Project water. Two others recharge effluent — the Sweetwater Wetlands, and the Santa Cruz River Heritage Project that discharges it into the river on Tucson’s south side.

Besides storing effluent, the site will be designed for public education about recharge and for demonstrating water-related technologies, Tucson Water said. They include water harvesting and the use of what’s known as dry wells, which take water into the aquifer instead of pumping it out.

Three dry wells already installed at the site are designed to allow stormwater runoff to more quickly infiltrate into the aquifer. One collects runoff from a reclaimed water reservoir on the site. Another collects it from the parking lot. The third well takes runoff from a landscaped area, MacAdam said.

As a way to learn more about the feasibility of capturing stormwater for future uses, the utility will measure how much of it is captured through the dry wells, monitor its quality and calculate how much it costs to maintain the dry wells.

The intent is to provide better information about how dry wells can be used elsewhere, MacAdam said.

“Though there are about 300 dry wells in use in Tucson, there is not a lot of good data about how they function here,” he said.

He added, “Part of the original vision for this facility, that we’re still committed to, is having it be a place where people can come and learn about water resources.”

But Pima County wastewater officials decided a few years back to pull out of their joint sponsorship because “first and foremost, the price tag was pretty pricey,” said County Wastewater Director Jackson Jenkins said.

He noted that of 43,204 acre-feet of effluent the county’s sewage plants dumped into the Santa Cruz in 2019, the federal government has rights to 28,200 acre-feet on behalf of the Tohono O’Odham Nation. Of what’s left, the city gets 90 percent and the county gets 10 percent under a decades-old agreement between the two governments. Since the county was already using some of that effluent, “it was not very economically viable” to send it to the Houghton Road recharge project, he said.

With the city also planning to charge the county almost $300 an acre-foot to have the water pumped uphill to the Houghton site for recharge, “It would have been very expensive water. It would not make economic sense to do that,” Jenkins said last week.

The county had already pulled out of the project by the time the prospect of additional pumping credits disappeared after the state law changed in 2019, Jenkins said, but without the extra credits, participation in the project would have been “ludicrous,” he said.

Tucson Water’s MacAdam, however, said the city utility still sees legitimate, water-related purposes for this project.

First, it allows the utility to keep more of its effluent within the state-run Tucson Active Management area for water, where the city can legally recover it by pumping out of the aquifer later, he said.

Second, the project gives the city extra capacity and flexibility for recharging effluent within the city’s service area, he said. If the effluent runs too far downstream from the sewage plants, it leaves the Tucson management area no longer can be legally recovered by the city.

While the city has no plans to recover recharged water from this site, it can recharge it at SHARP and recover it elsewhere, he said.

“As the community grows the effluent supply may grow, and we may need more capacity to recharge effluent,” MacAdam said.

Finally, this project creates a water-related demonstration and educational site on the east side for the first time, he said.

But Holler, the retired Bureau of Reclamation official, said he sees no water-related reasons for recharging reclaimed water at the new site. Since the water has already gone through two rounds of treatment, there’s no water quality reasons to recharge it again, he said. While it can make sense to recharge the reclaimed water for future use when it’s needed, possibly for drinking, it can be done more cheaply elsewhere, he said.

“This project is more of a park/recreational feature than a recharge feature,” Holler said. “In general, I don’t think it is financially feasible to use reclaimed water, which is already highly treated, for recharge because of the high cost of the reclaimed water.”