Toxic chemical releases from Arizona’s industries rose 70% in 2018 from 2017, a new EPA report shows.

But the company whose Pinto Valley Mine in Miami is reported to have by far the largest share of the increase says it gave the Environmental Protection Agency inaccurate totals of its releases.

When it corrects them, the 2018 release total should be in line with the figures it gave EPA for 2017, said Colleen Roche, a spokeswoman for Capstone Mining Corp.

If it turns out Pinto Valley had no increase in 2018, that would by itself override all other Arizona companies’ reported increases, leaving the 2018 statewide total a little below that of 2017.

The company has yet to provide corrected totals, nearly three weeks after informing the Star that its initial report to EPA was erroneous.

“Pinto Valley is focused on making sure that the data we amend the report with is accurate” before releasing it, Roche said.

At the same time, all but two of the other top 10 largest releasers after Pinto Valley showed higher totals for 2018 than for 2017.

Overall, 263 companies reported releasing 170 million pounds of toxic chemicals, heavy metals and other toxic substances in Arizona in 2018. About 100 million pounds were released in 2017.

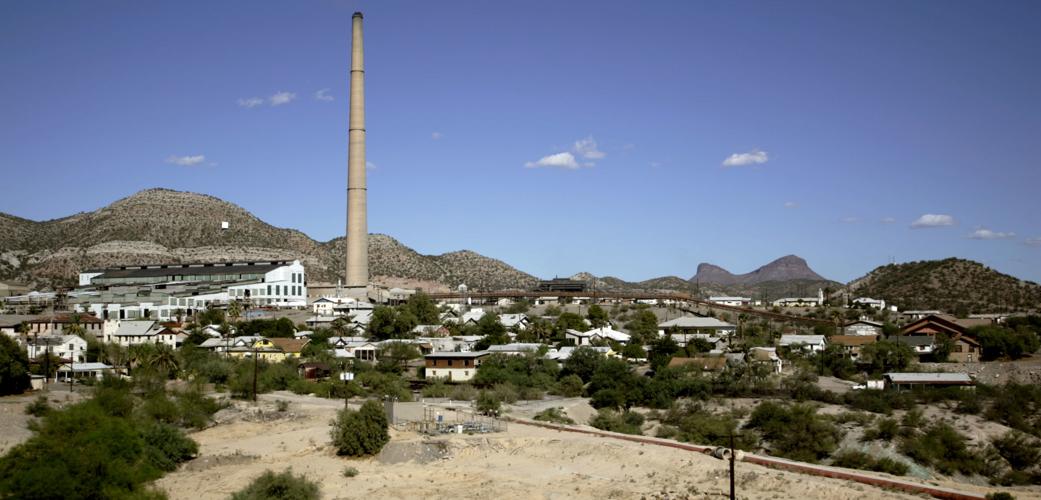

Pinto Valley’s mine ranked first with about 97 million pounds of 2018 releases, followed by Freeport McMoRan’s Miami smelter, with about 28 million pounds.

If Pinto Valley’s 2018 releases turn out to be the same as in 2017, it would rank second statewide. Miami lies about 125 miles north of Tucson.

Eight of Arizona’s top 10 ranked releases in 2018 came from copper mines and smelters.

They include Asarco’s Mission Mine complex in Sahuarita, which ranked fourth in 2018, and Freeport MacMoRan’s Sierrita Mine in Green Valley, ranking seventh. Both are within 30 miles south of Tucson.

Freeport’s mine in Morenci, nearly 175 miles northeast of Tucson, ranked fourth. Asarco’s smelter in Hayden, about 70 miles north of Tucson, ranked fifth. Freeport’s Bagdad Mine, nearly 240 miles northwest of Tucson, ranked eighth.

Nationally, the Pinto Valley Mine ranked fourth among all releasers, while the Freeport Miami smelter ranked 15th. The other three top-ranked Arizona mines finished in the top 30, nationally.

The Hayden smelter had at least a 70% decline in toxic releases in 2018. That happened after the EPA “came down on them like a ton of bricks,” said Eric Betterton, a University of Arizona atmospheric sciences professor.

EPA and Asarco signed a 2015 settlement for Asarco to spend $150 million on pollution control equipment upgrades, to meet federal clean air rules, said Betterton, who has done air monitoring work in the area.

By contrast, Freeport’s Miami smelter’s releases jumped 52 percent from 2017 to 2018. About 80 percent of that increase stemmed from increases in zinc concentrations in the materials the smelter processed, while the rest stemmed from an increase in copper concentrate production, Freeport spokeswoman Linda Hayes said.

Releases from Freeport’s Morenci Mine rose 42 percent in the same period. That was caused by an increase in zinc concentrations in the mine’s ore body, she said.

Asarco officials didn’t respond to requests from the Star to explain its major decrease in releases from its Hayden smelter or a nearly 75 percent increase in relesaes from its Mission Mine south of Tucson.

The other top 10 releasers were coal-fired power plants: TEP’s Springerville Generating Station in eastern Arizona, ranked sixth, and the now-closed Navajo Generating Station at Page, in northern Arizona, ranked 10th.

EPA’s toxic release inventory, commonly known as TRI, has been reporting releases of a wide range of chemicals and metals made to land, water and air by industries since 1988.

The releases are reported by industries, and are published more than a year after they occurred due to reporting time lags.

Nationally, releases have declined steadily since 2007. But they have varied widely over the years in Arizona, due in part to the mining industry’s up and down economic cycles.

The Arizona inventory showed that the top five ranked companies, all mines and smelters, together released at least a dozen chemicals and metals in 2018.

They include copper, copper compounds, lead and lead compounds, arsenic compounds, zinc, mercury, sulfuric acid, cadmium, and chromium.

Health risks debated

The releases’ risks have always been subject to debate.

EPA has said it can’t say whether they pose safety, health or environmental risks. They are simply raw numbers, lacking other information about how much people are exposed. The agency says it considers the inventory a starting point for analyzing risk.

The mining industry says the releases in most cases never pose health or environmental risks. The materials are contained in engineered structures on a mining property and heavily regulated under federal, state and local laws to prevent their release to the surrounding environment, said Conor Bernstein, a National Mining Association spokesman.

“Even though these metals and metal compounds occur in trace concentrations in nature, they appear as significant ‘releases’ in TRI reports because of the large amounts of earthmoving involved in mining and mineral processing operations,” Bernstein said. “Because of this, mining will always be the largest contributor of TRI ‘release’ data.”

Environmental groups have expressed major concerns about potential impacts from mine tailings and waste rock dumped onto the ground by mines after they’ve removed economically valuable minerals from raw ore.

Risks can occur when these materials are removed from their natural state, buried, compacted in the ground and exposed to air and water, said David Chambers, director of the Montana-based Center for Science and Public Participation.

It typically represents environmental and community groups and tribes in mining disputes.

“If you’re living next door to these things and the contamination comes off the site, it can be significant for you,” Chambers said.

Stressing the importance of this information, Chambers noted that the toxic release data back in the 1990s in Nevada let the public know that gold mines there were generating as much mercury releases as coal-fired power plants.

Without this information in Arizona, “when we have either a failure at a tailing dam or the wind blowing off tailings facilities, we wouldn’t know what’s in these tailings. That would make it even worse,” said Roger Featherstone, director of the Arizona Mining Reform Coalition.

Mine tailings the hottest issue

Year in and out, tailings are typically the largest single source of releases from mines.

Owners of both Tucson-area copper mines have paid fines and other settlements to Pima County after tailings blew onto neighboring homes and driveways, coating buildings, furniture and vehicles with thick sheens of white.

In October 2010, Asarco agreed to pay the county $100,000 in penalties and $350,000 for environmental projects. In 2018, the mine’s releases of toxic materials via tailings and waste rock disposal were, at more than 8 million pounds, more than four times greater than in 2010, EPA’s latest TRI report shows.

But county officials and neighboring residents say Asarco has far better tailings control now.

Freeport has received five tailings violation notices from Pima County since 2017. The most recent came in late January after dozens of Green Valley residents reported clouds of tailings dust coming from the Sierrita Mine.

Last year, the company agreed to pay $230,000 to settle earlier charges — $200,000 on an environmental project and $30,000 in penalties.

Last Monday, Feb. 24, the company sent a response to Pima County on its most recent violation notice.

It blamed the blowing dust on sustained winds exceeding 25 miles an hour.

The dust blew off-site, even though the company applied 224,000 gallons of water and 20,250 gallons of magnesium chloride, a dust suppressant, onto Sierrita’s tailings piles.

The company pledged to prevent future incidents, with measures including creating teams to manage the dust and respond to major windstorms, hiring a supervisor to manage one of the teams, and improving its use of aerial drone photography to monitor the tailings.

Mine tailings are a finely ground residue or dust that is generated from mining operations.

Excessive exposure to tailings can provoke or aggravate symptoms of asthma, bronchitis or other respiratory issues.

A 2010 University of Arizona study, however, concluded that the Asarco tailings, while definitely posing risks to respiratory patients, didn’t contain any higher concentrations of metals and metal compounds than what exists in the ground.

Chambers notes, however, that chemicals and metals in tailings have contaminated groundwater in various places, including that underlying several Southern Arizona mines, including Sierrita.

There, Freeport has pumped and reused sulfate-contaminated groundwater for years.

At Morenci, where tailings represent 98.5% of that mine’s toxic releases, they’re managed on site “in a safe and environmentally responsible manner under permits with the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality,” Freeport spokeswoman Linda Hayes said.

Storm water runoff from tailings and tailings water that discharges to groundwater are collected for reuse at the mine, Hayes said.

Similarly, Pinto Valley spokeswoman Roche said its officials don’t see health or environmental risks associated with their operation.

“We have a robust risk management and permit compliance program and we strive for 100% compliance,” Roche said.

Tailings dams at issue at Pinto Valley

Environmentalists are concerned about another type of tailings risk at that site — from the company’s proposal to expand operations onto U.S. Forest Service land.

As part of the proposed expansion, now under Forest Service review, the company wants to raise a tailings containment dam from 750 feet to 1,045 feet, almost as tall as the Eiffel Tower.

The expansion would push the mine’s closure date back from 2027 to 2039.

In comments on the service’s draft environmental impact statement on the mine, environmentalists including the mining reform coalition and Sierra Club noted that the statement warned this proposal “would allow more tailings to be stored at Pinto Valley Mine and increase the risk to public health and safety in the event of a tailings storage facility failure.”

At worst, a major breach of that or a second large tailings dam could cause tailings to flow downstream in neighboring Pinto Creek 21 miles to Roosevelt Lake, the environmental statement said.

In response, Capstone spokeswoman Roche said the company takes its tailings management responsibilities very seriously and strives to keep ahead of evolving industry standards.

Its proposed dam height increases “are consistent with demonstrated safe industry practices and are designed with the health, safety, and welfare of our environment, community and workers in mind,” Roche said.