Air pollution noticeably dropped across the Tucson area in the past two months compared to years past, as the coronavirus pandemic caused tens of thousands of people here to stop or limit their driving.

This comes, however, as the region’s air quality has worsened in recent years, though it’s better than a decade or two ago, says a report released for Wednesday’s Earth Day by a health advocacy group.

And while no one wants a pandemic to be the way to reduce air pollution, the recent declines offer potential guideposts for how to cut pollution over the long term, Pima County and American Lung Association officials say.

Specifically:

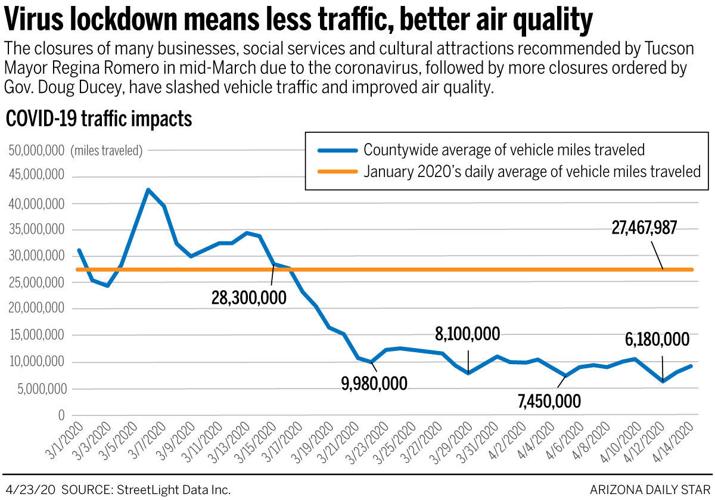

- As of mid-April, the number of miles traveled by cars, trucks and other motor vehicles had dropped about 78% since March 15, when Mayor Regina Romero instituted the first of several government-ordered shutdowns of local businesses and other services.

- In the same period, the levels of a key ingredient in the chemical mix that forms ozone dropped significantly from a year ago at two county-run air-quality monitors on Tucson’s northwest and east sides.

The monitors measure ambient air levels of nitrogen dioxide, which reacts with volatile organic compounds in the air and sunlight to form ozone. A toxic pollutant, ozone can trigger coughing, throat irritation, lung damage and chest pains, particularly in people already suffering from respiratory problems such as asthma and bronchitis. Nitrogen dioxide primarily gets into the air through the burning of fuel, including by motor vehicles, the Environmental Protection Agency says.

- At a third county monitor on the city’s south side, levels of fine particles, which also can trigger serious lung problems, were also down significantly this spring compared to spring 2019.

- However, Pima County scored an F for ozone air pollution in the latest annual State of the Air report, released this week by the lung association. That report covered 2016 through 2018, the most recent years for which the association could obtain and analyze local air quality data.

- In those years, the county experienced 14 days in which ozone levels exceeded the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency daily standard of 70 parts per billion, the report says. That’s more bad air days than during the three-year periods covered by the four lung association reports before this one. At the same time, however, the number of bad air days in 2016 through 2018 is still far lower than in the 1990s or the 2000s.

The same short- and long-term trends are occurring in many cities nationally, as well.

“Nothing about COVID is something to be happy about,” said Ursula Nelson, director of the Pima County Department of Environmental Quality, referring to COVID-19, the illness caused by the coronavirus.

“Having said that, as anyone who’s driving around town can tell, clearly there are many, many fewer cars on the road. You can draw some conclusions about the links to air quality, although not definitive, because it’s too early in the year,” Nelson said.

Motor vehicles are typically the biggest source of this area’s air pollution, she has said.

She added: “I would like people to think about the fact that now is the kind of time to look at habits we all fall into and ask, ‘Is there room to make changes in what we do on a regular basis to have less impact on the environment?’”

Although we can’t expect a pandemic to be the “saving grace” cleaning the air forever, there’s something to learn from this experience, said Joanne Strother, the lung association’s senior advocacy director.

“It really shows the path forward — what getting cars off the road or getting cleaner cars could do for our cities,” said Strother, who is based in Phoenix, where the air is typically far more polluted than Tucson’s.

Nationally, recent ozone levels in particular are worsening in many cities, the State of the Air report said. In the years covered by the newest report, more than 137 million people lived in 205 counties including Pima with an F rating, the report said — significantly more counties than in the previous three reports.

“Why? Increased heat,” said the report, citing long-term climate change. “The three years in this report were three of the five warmest years on record” nationally.

In Tucson, 2016, 2017 and 2018 were also among the five warmest years here since records started being kept in 1895, the National Weather Service has said.

There is a definite link between warmer weather and ozone formation, though it’s not the only factor, said Beth Gorman, program manager for Pima County DEQ.

Warmer weather increases evaporation of volatile organic chemicals into the air, whether from gasoline and other fluids in cars, toxic solvents or even from plants, she said. The VOCs react with the nitrogen dioxide in the presence of sunlight to form ozone.

Elsewhere in Arizona, Maricopa, Pinal, Gila and Yuma counties also got F grades for ozone in the lung association’s latest report. For fine particles, Tucson got a B, while Maricopa and Pinal counties got F’s.

Nelson said that based on criteria the lung association uses for setting grades, Pima County’s F for ozone is correct. But the county uses a different standard to rate its air — the EPA’s formal determination of whether Pima meets EPA air quality limits over a three-year period, she said.

Using that standard, Pima County was in jeopardy of being declared out of compliance for ozone for 2016 to 2018. In 2019, however, ozone levels were much lower than in the previous three years, putting the county back in line with the EPA standard, Nelson said.

As for why 2019’s levels were lower, “I would speculate that we typically have lower ozone when it’s not as hot, when there’s more wind or when it’s more overcast — so weather-related aspects,” Nelson said.

And 2019 was definitely cooler and wetter than the previous few years. It ranked as the 17th hottest year on record here, whereas the previous five years were the hottest five on record. Also, Tucson got 2 more inches of rain than normal in 2019. More rain means more clouds, less sun, less ozone.

But just because the county is in compliance right now doesn’t mean the community doesn’t need to reduce ozone pollution, Nelson said.

“Ozone is definitely a challenge for this community,” she said. If we weren’t in a pandemic that’s already slashed traffic, “typically what we’d be asking people to do is to drive less.”