PHOENIX — A promise by Gov. Doug Ducey to protect state aid for schools during the pandemic is coming up short.

In some cases, a lot short.

Ducey announced in June he was setting aside $370 million in federal cash to cushion schools against budget shortfalls due to anticipated enrollment declines.

“This will ensure budget stability, even with more students participating in distance learning, and provide dollars when students are learning in the traditional classroom setting,” Ducey said in a news release about his program. He said he recognized “the additional costs in-person learning will bring to districts this school year.”

In essence, Ducey said his plan would guarantee that schools will have at least 98% of the state aid they were getting last school year.

That is crucial for schools, as the money they get from the state is based on the number of students in attendance. And even with schools being allowed to count students who are in online-only learning situations, the number is off — sharply.

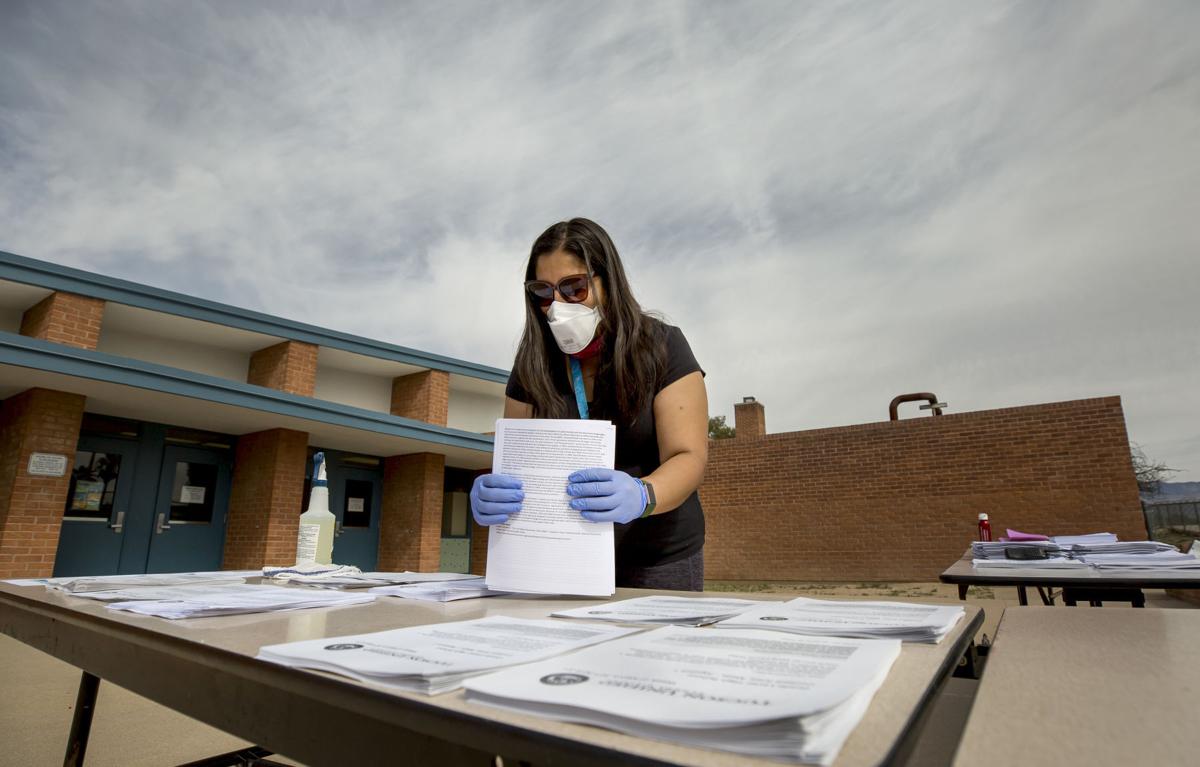

Warehouse workers at the Tucson Unified School District Food Services Department building unload coolers and crates from buses returning from grab-and-go distributions. The TUSD Food Services Department has continued to provide services for students and families throughout the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic and is currently providing about 30,000 meals a week for students. (Josh Galemore / Arizona Daily Star)

Last year, the regular “average daily membership” count was 1,117,521.

This year, on Nov. 3, a benchmark for determining aid, the count was down by 3.7%.

And the requests for money from what was dubbed the Enrollment Stability Grant program exceeded the $370 million available. So, when the grants actually were made last week, a lot of districts were left in the lurch.

In Tucson Unified School District, for example, officials figured they were due about $20.5 million. They got less than $15.3 million.

At the nearby Amphitheater district, a $5.6 million allocation fell short of the $10 million expected.

Chandler Unified School District wasn’t hit as hard, getting about $14.3 million out of the nearly $15.6 million it expected.

Smaller districts also got hit, like the Casa Grande Elementary School District, which found itself more than a half million dollars in the hole.

“This hurt us,” said Joetta Gonzales, the district superintendent. “Like many other surrounding districts, we have experienced a substantive decline in enrollment this year.”

Daniel Scarpinato, the governor’s chief of staff, does not dispute that schools are getting less than they thought they would receive.

But he said, in effect, that the schools should be pleased with what they’re getting, as governors in other states have not agreed to any supplemental funding and, in some cases, have cut K-12 dollars in the wake of the pandemic.

Scarpinato said the bottom line is that schools are getting less state aid because they just don’t have the same number of students they did before the virus. He said there are multiple reasons, suggesting some of these are the fault of districts themselves and the choices they make.

“One of them is students transferring to schools that are offering in-person learning,” Scarpinato said. He also said there are “massive amounts of digital truancy” where students are enrolled in online learning but not logging in and therefore not being counted for attendance.

But Kathy Hoffman, the state superintendent of public instruction, said she believes schools are being shortchanged.

“The ESG program was intended to provide much-needed budget stability for schools as they planned for this tumultuous year,” she said.

Hoffman said schools made plans based on the promised dollars to fund everything from COVID-19 mitigation strategies — such as masks, plastic shields and hand-washing stations — to setting up distance learning programs.

“Based on the allocations provided to schools last week, the state has broken that promise,” Hoffman said.

Scarpinato said he doesn’t see it that way.

He said Arizona schools got $716 million from the federal Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act.

But Ducey had nothing to do with $346 million of that, with schools getting their own allocation directly from Washington. Scarpinato said it was the governor’s decision to use some of his own allocation to voluntarily add to what they were getting.

“Frankly, I don’t believe many, if any states, have done anything like this to provide additional CARES dollars beyond what the federal government specifically earmarked for K-12 education,” Scarpinato said.

Ducey has more federal cash at his disposal.

In fact, of the nearly $1.9 billion appropriation that was given directly to the governor, he sent $400 million to state agencies for their own operations, including salaries. They then used the federal infusion to give some of their budgeted dollars back to the state.

Scarpinato is unapologetic about using those CARES funds for basic state government operations instead of issues directly related to the pandemic.

“It’s really important for the education community and for public schools that we have budget stability,” he said.

Without that, Scarpinato said, Arizona would be in the same position as other states whose economies have been buffeted by the COVID-19 outbreak where budgets have had to be cut, including education funding.

Anyway, he said, the $370 million is more than the districts would have gotten following the basic state aid formula, which is tied to attendance.

But the shortage of funds is only part of the issue.

The additional aid was designed to go out on a per-student basis. Put simply, the amount of aid to get districts back to the 98% level was linked to how many students they were short.

But the governor’s office decided to impose a cap of $500 per student. So the districts with the biggest losses are not getting anywhere close to the 98%; moreover, they are getting an even smaller share than some other districts where the attendance losses have not been as great.

One of the districts affected was Amphitheater. Scott Little, the district’s chief financial officer, said that makes no sense, given that the whole purpose of the money was to provide help based on financial need.

“It’s like arriving at the scene of an accident and killing the most injured patient,” he said.

Scarpinato said the $500 cap was based on guidance from the U.S. Treasury Department.

Photos: July Motormarch 2.0 for Safe Schools in Tucson

Motormarch 2.0 for Safe Schools

Updated

Ryer Dixon helps get her family car decorated as a few hundred get their vehicles in the proper protest spirit for the Tucson Motormarch 2.0, staging at Hi Corbett Field, Tucson, Ariz., July 22, 2020. The protestors were advocating for a delay in the opening of in-school classes in light of Arizona's rocketing COVID19 numbers. The motorcade took a circuitous route through southwest Tucson ending at Sentinel Peak.

Motormarch 2.0 for Safe Schools

Updated

Tucson High School biology teacher Marea Jenness writes her protest message in her car's windows as a few hundred get their vehicles decorated for the Tucson Motormarch 2.0 while staging at Hi Corbett Field, Tucson, Ariz., July 22, 2020. The march was organized to protest the opening of in-school classes in light of Arizona's rocketing COVID19 numbers.

Motormarch 2.0 for Safe Schools

Updated

Cholla High School teacher Jose Federico waves as he counts the vehicles heading down from Sentinel Peak as a few hundred protestors wrap up the Tucson Motormarch 2.0 while staging at Hi Corbett Field, Tucson, Ariz., July 22, 2020. Heading out organizers counted 170 vehicles, Federico totaled up 148 heading off the mountain.

Motormarch 2.0 for Safe Schools

Updated

Jaye Harden climbs up on the trunk to get the best possible angle for writing on the rear window as a few hundred protestors get their vehicles decorated for the Tucson Motormarch 2.0 staging at Hi Corbett Field, Tucson, Ariz., July 22, 2020.

Motor March for Safe Schools

Updated

Andrea Ayala, a teacher at Pueblo High School, advocated for keeping campuses closed during a July 15 Motor March for Safe Schools in Tucson, Ariz.

Motor March for Safe Schools

Updated

One of about 100 cars filled with Tucson Unified School District educators and supporters participate in a Motor March for Safe Schools in downtown Tucson on July 15, 2020.

Motor March for Safe Schools

Updated

About 100 cars filled with Tucson Unified School District educators and supporters participate in a Motor March for Safe Schools on July 15, 2020 in Tucson, Ariz.

Motor March for Safe Schools

Updated

Lysa Nabours, a teacher and secretary at Tucson Education Association, checks out her decoration on a car before the start of the March for Safe Schools on July 15, 2020 in Tucson, Ariz.

Motor March for Safe Schools

Updated

About 100 cars filled with Tucson Unified School District educators and supporters participate in a Motor March for Safe Schools on July 15, 2020 in Tucson, Ariz.

Motor March for Safe Schools

Updated

About 100 cars filled with Tucson Unified School District educators and supporters participate in a Motor March for Safe Schools on July 15, 2020 in Tucson, Ariz.

Motor March for Safe Schools

Updated

Tucson Unified School District educators and supporters participate in a Motor March for Safe Schools on July 15, 2020 in Tucson, Ariz. About 100 cars and a few cyclists showed up for the event that was part of a statewide initiative to make political leaders aware of their concerns about opening schools for in-person instruction during a rise in COVID-19 cases.

Motor March for Safe Schools

Updated

Ryan Kuchta, 13, middle, is joined by his parents, Mark and Sonya, as they show their support for educators during the Motor March for Safe Schools event on July 15, 2020 in downtown Tucson.

Motor March for Safe Schools

Updated

About 100 cars filled with Tucson Unified School District educators and supporters participate in a Motor March for Safe Schools on July 15, 2020 in Tucson, Ariz.