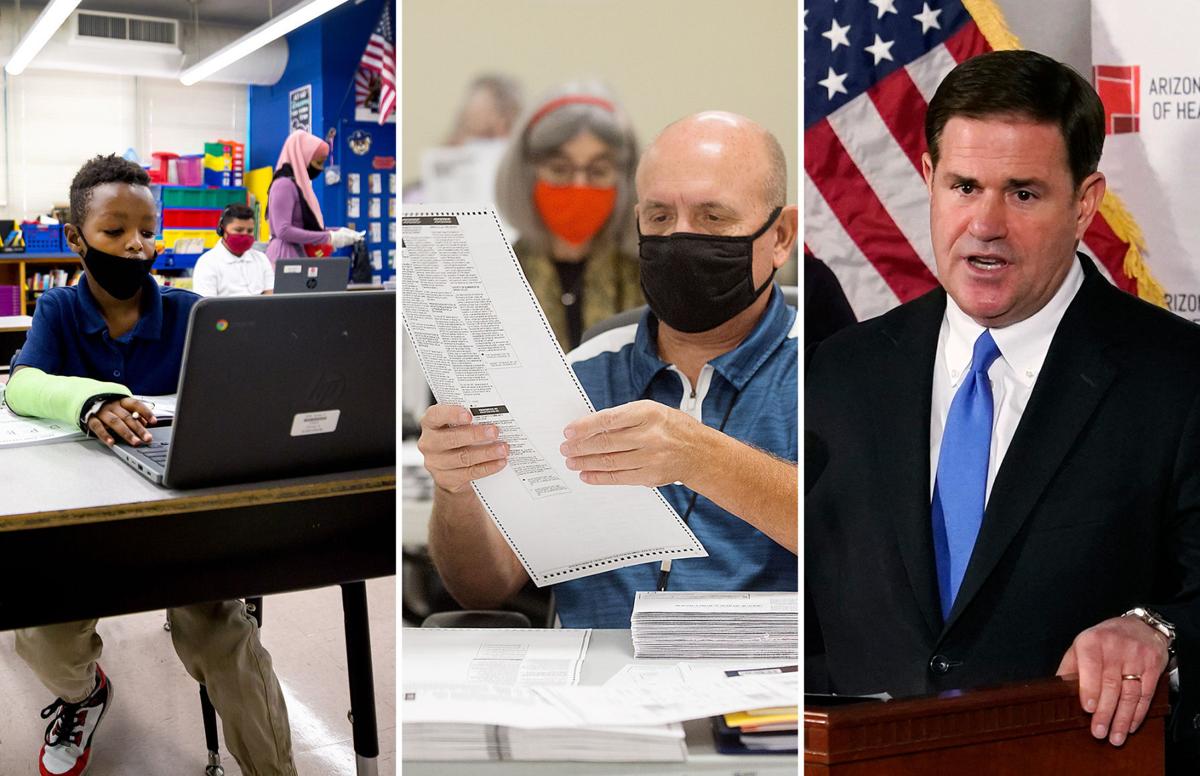

PHOENIX — The 2021 legislative session is being brought to you by the letter E.

As in emergency powers, election legislation and education funding.

The session will get off to a quick start as one of the lawmakers’ first acts will be to determine whether it’s time to pull the plug on the state of emergency that Republican Gov. Doug Ducey declared 10 months ago because of the pandemic.

If there’s a majority vote in the GOP-controlled Legislature to end the declaration, the governor cannot veto it.

Sen. Michelle Ugenti-Rita, R-Scottsdale, already has the language crafted. Her measure, SCR 1001, seeks to take advantage of a provision in the law that gave Ducey the power to unilaterally declare an emergency in the first place. It says the emergency ends when the governor says it does — or when a majority of legislators vote to say it’s over.

Legislators haven’t been able to debate the issue until now because they weren’t in session. It takes either a gubernatorial call, one Ducey was not going to provide, or a two-thirds vote to end the emergency declaration.

Now, with the session starting Monday, Jan. 11, Ugenti-Rita will need 16 senators and 31 representatives to side with her.

But there’s no clear law about whether the governor can simply turn around and declare a new one and reinstate all the provisions, including which businesses can be open and under what conditions.

That possibility has Rep. John Kavanagh, R-Fountain Hills, asking Republican Attorney General Mark Brnovich whether that would require the Legislature to take another vote to swat down the governor. He also wants to know whether that would automatically terminate any reinstated actions “or would a court have to issue an order?”

Then there’s the question of whether lawmakers have other options. For example, Kavanagh wants to know whether the Legislature could impose a self-destruct measure into an existing emergency declaration, such as saying it has to end when hospitalizations or coronavirus case numbers drop below a certain level.

Ducey, in an interview with Capitol Media Services, said pulling the plug on his declaration would be a bad idea.

“We’re still in that public-health emergency,” he said. “That’s why state law and the constitution provide for executive emergency authorities in situations like that.”

Even if a majority of legislators won’t immediately quash the emergency declaration, there is broader support to reviewing the underlying laws that allowed Ducey to declare it in the first place.

Rep. Mark Finchem, R-Oro Valley, wants a constitutional amendment sent to the ballot to require governors to get “advice and consent” of the Legislature within a certain period, perhaps 14 days, of declaring an emergency.

He said the state’s chief executive would need to provide lawmakers with “evidence that an emergency exists” under that proposal.

Even those who may look for less drastic measures think the law needs to be revisited.

Senate President Karen Fann, R-Prescott, and House Speaker Russell Bowers, R-Mesa, put together a special panel to review the statutes.

Their specific goal is to determine if there’s the proper balance between the needs of the governor to respond to unforeseen events, and the role of the Legislature in providing oversight. Fann said she’s not sure that lawmakers, in adopting the original laws, had in mind what Ducey has done.

“The assumption (was it) would be a Rodeo-Chediski Fire,” she said, referring to the 2002 blaze that burned more than 468,000 acres in Eastern Arizona, “or a 9/11 or something that would last a short duration.”

“Nobody foresaw that it would be something like this that could potentially go on for months,” Fann said.

Ducey said he’s willing to listen.

“I’m open to ways we can improve our laws or policies in light of the knowledge that we have, having gone through our first pandemic in the history of the state,” he said.

The National Conference of State Legislatures says that in six states the expanded power of the governor in an emergency has a built-in expiration date of between two and 60 days, depending on the state and the type of emergency.

In our first post-election chat, journalist Mort Rosenblum give us his thoughts on the election, Joe Biden and his life on a houseboat in France.

Election laws

State election laws present a different set of issues.

Arizona already has statutes designed to prevent fraud and determine the accuracy of vote counts.

For example, unlike in some states, early ballots are mailed only to those who request them, whether on an election-by-election basis or signing up for the permanent early voter list.

And the law requires a hand count of the votes from 2% of precincts or vote centers, comparing what the machines tallied with what humans determine .

“I do think we do elections well,” Ducey said.

Still, there are suggestions for change.

Sen. J.D. Mesnard, R-Chandler, wants the hand count increased to 5%, and to add provisions allowing the attorney general, the secretary of state or the legislative council to demand more.

Potentially more sweeping, Mesnard also wants to allow anyone with enough money to cover the costs to demand a full recount of any election. Now, the only way that happens is if the margin of victory falls within certain margins, like 200 votes for a statewide race.

There is some discussion about tightening up the permanent early voter list, requiring names be purged if people don’t vote in two election cycles and don’t respond to a postcard asking if they want to continue to get early ballots.

And then there are proposals that stem from the 2020 election controversies.

Take “Sharpiegate.” That’s the claim that felt-tipped pens used in some counties at polling places bled through to the other side of the two-sided ballots, affecting votes and resulting in some ballots not being counted.

Sen. Kelly Townsend, R-Mesa, wants to bar county officials from mandating the use of any specific marker.

Maricopa County officials said Sharpies are the marker recommended by the manufacturer of the counting machines because the ink dries quickly while other pens leave smears in the machines, which require them to be taken off-line and cleaned. And races on the back of the ballot are offset so that a stray bleed-through on one side could not affect choices on the back, they said.

Townsend conceded to Capitol Media Services she has an ulterior motive.

“In order to comply with the legislation, they will have to terminate their lease with Dominion (Voting Systems) and go with a different company,” she said, saying those other firms don’t allow use of Sharpies. Dominion has been the target of various conspiracy theories, all unproved in multiple lawsuits, that its hardware and software were programmed to add votes for Joe Biden and to not count all of the votes cast for President Trump.

Ducey, when asked about state election laws, said, “I am concerned with the amount of distrust and the erosion of trust that’s happening in elections across the country.”

The governor said he’s open to ideas to make elections here more secure.

But Ducey said he believes some of the issues undermining confidence in the state’s election returns — the returns he certified as accurate — are a matter of public education.

“We need to do a good job of communicating how we do things in Arizona that differentiates us from places like Pennsylvania, Nevada or Michigan,” he said.

Education money

The issue of education funding involves what Sen. Paul Boyer, R-Phoenix, says is a broken promise.

When the pandemic hit, schools went to online learning. But the state funding formula provides fewer dollars for each child who is not sitting in a classroom. On top of that, some students didn’t come back, leaving districts with fixed costs but less state aid, which is based on the number of students.

Ducey announced in June that he was setting aside $370 million to guarantee that schools this academic year would have at least 98% of the funding they were getting last year. But that money ran out, leaving many districts with less.

“I really think we need to make sure we deliver on our promises,” said Boyer, who chairs the Senate Education Committee.

But Ducey said not to look for him to supplement that $370 million appropriation. That, he said, was the commitment.

“That’s been sent to schools,” he said. “Unfortunately, districts saw much higher declines in enrollment than they originally anticipated.”

Anyway, the governor said, there are other dollars that have been sent to schools. Boyer acknowledged there is additional federal funding for education. But he said that is earmarked for Title I schools, those where a large percentage of children come from low-income families.

“It doesn’t help the non-Title I schools,” he said.

Boyer said he is still trying to figure out how much more schools need, either because of the lower reimbursement for online learning or declining enrollment.

Each district is different. Boyer said the Glendale district, where he lives, lost about $8 million.

“That’s a huge number,” Boyer said.

He said that, whatever the amount is owed to schools statewide, it’s not fair to provide less than promised.

Photos: Teacher protests at Arizona Capitol on April 30

Teacher protest in Phoenix

Updated

Teachers rally outside of Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey's Executive Tower Monday, April 30, 2018, in Phoenix on their third day of walk outs. Teachers in Arizona and Colorado walked out of their classes over low salaries keeping hundreds of thousands of students out of school. It's the latest in a series of strikes across the nation over low teacher pay. (AP Photo/Matt York)

Teacher protest in Phoenix

Updated

Rep. Mark Cardenas, D-Phoenix, talks to teachers and RedForEd supporters about how the education budget will not be debated till Tuesday or Wednesday of this week, during the third day of the Arizona teacher walkout in the Arizona State House at the Arizona State Capitol in Phoenix on Monday, April 30, 2018.

Arizona teacher walkout #RedForEd

Updated

Rep. Eric Descheenie, D-Chinle, walks through a crowd of teachers and supporters on the third day of the Arizona teacher walkout at the Arizona State Capitol in Phoenix on Monday, April 30, 2018.

Teacher protest in Phoenix

Updated

Teachers rally outside the Capitol on Monday, April 30, 2018, in Phoenix on their third day of walk outs. Teachers in Arizona and Colorado walked out of their classes over low salaries keeping hundreds of thousands of students out of school. It's the latest in a series of strikes across the nation over low teacher pay. (AP Photo/Matt York)

Teacher protest in Phoenix

Updated

Teachers rally outside of Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey's Executive Tower Monday, April 30, 2018, in Phoenix on their third day of walk outs. Teachers in Arizona and Colorado walked out of their classes over low salaries keeping hundreds of thousands of students out of school. It's the latest in a series of strikes across the nation over low teacher pay. (AP Photo/Matt York)

Teacher protest in Phoenix

Updated

Teachers and supporters of the #RedforEd movement strike outside the state capitol on day three of the teacher walkout on Mon. April. 30 2018 in Phoenix, Arizona.

"If you think education is expensive, wait until you see how much ignorance costs."

Updated

Teachers and other supporters rally during the the third day of the Arizona teacher walkout at the Arizona State Capitol in Phoenix on Monday, April 30, 2018.

Teacher protest in Phoenix

Updated

Teachers and other supporters walk rally during the the third day of the Arizona teacher walkout at the Arizona State Capitol in Phoenix on Monday, April 30, 2018.

Teacher protest in Phoenix

Updated

Arizona teachers gather in the lobby of the Senate building at the Arizona State Capitol during Day 3 of a walkout for higher pay and more education funding on Apr. 30, 2018 in Phoenix, Ariz. (Photo by Rob Schumacher/The Arizona Republic)

Teacher protest in Phoenix

Updated

Winslow teacher Nicole Tell (right) joins her follow Arizona teachers at the Arizona State Capitol during Day 3 of a walkout for higher pay and more education funding on Apr. 30, 2018 in Phoenix, Ariz. (Photo by Rob Schumacher/The Arizona Republic)

Teacher Protests

Updated

Arizona state Sen. Steve Farley, standing, introduces teachers from his Tucson district who were among those packing the Senate gallery while striking for better pay and school funding in Phoenix, Ariz., Monday, April 30, 2018. (AP Photo/Bob Christie)

RedForEd

Updated

State Rep. Isela Blanc is greeted by "Red For Ed" supporters, April 30, 2108, at the Arizona capitol in Phoenix on the third day of the Arizona teacher walkout.

RedForEd

Updated

State Rep. César Chávez, LD 29, is greeted by "Red For Ed" supporters, April 30, 2108, at the Arizona capitol in Phoenix on the third day of the Arizona teacher walkout.

RedForEd

Updated

State Rep. César Chávez, LD 29, is greeted by "Red For Ed" supporters, April 30, 2108, at the Arizona capitol in Phoenix on the third day of the Arizona teacher walkout.

Arizona teacher walkout #RedForEd

Updated

Rep. Daniel Hernandez, D-Tucson, walks through a crowd of teachers and supporters on the third day of the Arizona teacher walkout at the Arizona State Capitol in Phoenix on Monday, April 30, 2018.

Arizona teacher walkout #RedForEd

Updated

Teachers and supporters join hands on the third day of the Arizona teacher walkout at the Arizona State Capitol in Phoenix on Monday, April 30, 2018.

Arizona teacher walkout #RedForEd

Updated

Sam Camacho, music teacher Paradise Valley Unified School District (from left) and Kayla Pierce and Alexandra Jacques, both music teachers at Mesa Public Schools, of the RedForEd Spirit Band play music on the third day of the Arizona teacher walkout at the Arizona State Capitol in Phoenix on Monday, April 30, 2018.