PHOENIX — The state’s top Republican lawmakers have ordered a closer look at whether the governor’s powers should be curtailed, seven months into an emergency declared by Republican Gov. Doug Ducey.

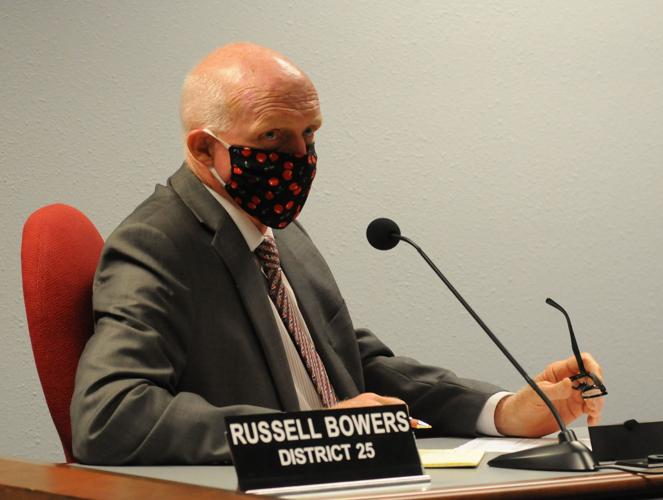

Senate President Karen Fann, R-Prescott, and House Speaker Rusty Bowers, R-Mesa, formed a panel to review the issue. It is charged with trying to determine if Arizona has the proper balance between the need of the state’s chief executive to respond to unforeseen events, and the role of the Legislature in providing oversight.

Issues will range from what is needed to trigger a gubernatorial declaration of an emergency, to exactly how long it can go on without needing legislative approval.

That last issue has become a sore point among some lawmakers who note that Ducey declared an emergency in March due to COVID-19 that is still in effect, with no hint from the governor of when he’ll be ready to declare it over.

All indications are that won’t happen soon.

Ducey continues to use those emergency powers to limit the operations of businesses through occupancy limits, bans on evictions, prohibitions against dancing in bars, and more.

Here are common hand sanitizer mistakes you’re probably making, and simple ways to fix them. Buzz60’s Chloe Hurst has the story!

Dr. Cara Christ, the state’s health director, has said she expects that bars, now closed for normal operations under Ducey’s directives, will not be able to resume normal operations until sometime next year.

State and federal judges have so far rebuffed various legal challenges to Ducey’s authority, saying the existing laws give him wide latitude, even to override certain laws.

And Brett Johnson, a private attorney hired by Ducey — and paid with taxpayer dollars — has told judges there is no reason for them to intercede because lawmakers remain free, with a simple majority vote, to cancel any emergency.

That, however, is not a realistic solution when the Legislature is not in session, as is currently the case: It takes a petition with two-thirds of both the House and Senate for lawmakers to call themselves in to even have the vote.

Fann said this isn’t about Ducey. She said the governors of all 50 states and the president all have had to deal with the pandemic.

But she said the current situation isn’t what Arizona lawmakers had in mind when they granted governors broad powers.

“The assumption (was it) would be a Rodeo-Chediski Fire,” the 2002 blaze that burned more than 468,000 acres in eastern Arizona, “or a 9/11 or something that would last a short duration,” Fann said. “Nobody foresaw that it would be something like this that could potentially go on for months.”

Ducey appears cool to the idea of reviewing his powers, at least while he’s still exercising them.

“These are unprecedented times, and there will be plenty of time for after-action reports once we’ve navigated through what’s in front of us,” said his press aide Patrick Ptak.

He said Ducey is following the laws as they now exist.

But Sen. Michelle Ugenti-Rita, R-Scottsdale, who will co-chair the panel, said she already has some ideas of things that need to change in the statutes.

One would be some sort of time limit on how long an emergency could last without getting the approval of state lawmakers for an extension. There could be some flexibility in how that is crafted, Ugenti-Rita said.

But she said the current situation is not acceptable.

“We’ve been in this now for seven months,” she said. “So clearly, we have moved out of an emergency. Now we’re just in a state of crisis, I guess?”

The result is that one branch is running the government, she said.

There is precedent for an approach such as she suggests.

The National Conference of State Legislatures says that in six states, the expanded executive power under an emergency has a built-in expiration date of between two and 60 days, depending on the state and the type of emergency.

“It makes sense that we have triggers in place and statutes in place to deal with unprecedented situations,” Ugenti-Rita said.

“But this has gone on for far too long, with no end in sight, minimal communication (from the governor) about what to expect,” she continued. “It’s completely gutted the Legislature and we need to bring back the balance of power.”

Arizona has two separate sets of laws on emergencies.

The state Health Code provides broad authority for the Department of Health Services during a state of war or a gubernatorial-declared emergency “in which there is an occurrence of imminent threat of an illness or health condition caused by bioterrorism, an epidemic or pandemic disease, or a highly fatal infectious agent or biological toxin that poses a substantial risk of a significant number of human fatalities or incidents of permanent long-term disability.”

Those powers include mandating treatment of vaccinations of those who have been exposed, quarantining some individuals, mandating medical examinations for exposed persons, and rationing of medicine and vaccines.

The more sweeping powers are in a separate section of Arizona law. These give a governor who has declared a state of emergency “the right to exercise, within the area designated, all police power vested in the state.”

In fact, the only statutory limit lawmakers have put on the governor in these situations is that he or she cannot impose new restrictions on the possession, transfer, sale, carrying, storage, display or use of firearms.

Ducey has cited that section of law this year in everything from a now-expired stay-at-home order, to prohibiting residential evictions, to telling businesses including restaurants, bars, gyms, fitness centers and water parks how they can operate.

A recent court filing by Republican Attorney General Mark Brnovich underlined the fact that there are “no set criteria” for ending the emergency, with the result that “the governor has claimed for himself the indefinite power to act legislatively.”

Ugenti-Rita, who will co-chair the panel with Rep. Gail Griffin, R-Hereford, said she wants to begin hearings “like yesterday.”

The idea of the review is not unique to Arizona.

Lawmakers in at least 23 states have introduced bills or resolutions that would limit the power of the governor or the authority to spend money without legislative approval, the National Conference of State Legislatures reports.

For example, one option is to require that a governor at least give notice to lawmakers when suspending enforcement of certain statutes. Another is to tell lawmakers how money is being spent.

Photos for May 29: Tucson gets by during Coronavirus Pandemic

Tucson gets by during coronavirus pandemic

Updated

The iconic Casa Molina bull and matador statue both sport masks on the first full week of the loosening of COVID19 restrictions, May 23, 2020, Tucson, Ariz. The bull previously had a mask on the testicles.

Tucson gets by during coronavirus pandemic

Updated

Michelle Leon Cordova, right, mother, and her son Sahuarita High School senior Lino Cordova, whom is fighting cancer, wave at staff members from Diamonds Children Center, friends and the Marana Police Department during a car parade, celebrating Lino's graduation, outside of his home on May 13, 2020 in Sahuarita, Ariz. Cordova stood on the sidewalk while the team from Diamond Children Center, friends and the Marana police department gave Cordova a graduation gar parade. Cordova was given a gift basket with his favorite snacks, gift cards as well as other items he enjoys. The car parade, also, celebrated another graduating senior fighting cancer from Empire High School, Noah Nieto. Nieto, also, received a gift basket with snacks, gift cards and other items Lino enjoys.

Tucson gets by during coronavirus pandemic

Updated

Michelle Leon Cordova, right, mother, brings celebration balloons to a car after staff members from Diamonds Children Center, friends and the Marana Police Department celebrate Sahuarita High School senior Lino Cordova, whom is fighting cancer, graduation with a car parade outside of his home on May 13, 2020 in Sahuarita, Ariz. Cordova stood on the sidewalk while the team from Diamond Children Center, friends and the Marana police department gave Cordova a graduation gar parade. Cordova was given a gift basket with his favorite snacks, gift cards as well as other items he enjoys. The car parade, also, celebrated another graduating senior fighting cancer from Empire High School, Noah Nieto. Nieto, also, received a gift basket with snacks, gift cards and other items Lino enjoys.

Tucson gets by during coronavirus pandemic

Updated

Personnel from Tucson Medical Center line the heliport to watch A-10's from Davis-Monthan Air Force Base's 355th Wing and F-16's from the Arizona Air National Guard's 162nd Wing make a pass over the facility, one leg of an area wide community flyover, May 14, 2020, Tucson, Ariz.

Tucson gets by during coronavirus pandemic

Updated

Nancy Celix-Campos, right, a respitory therapist at Tucson Medical Center, watches the military flyover with her daughters, Giana, 12, and Jazmyn, 8, from Sentinel Peak on May 14, 2020. Two F-16 Fighting Falcons from Arizona Air National GuardÕs 162nd Wing and two A-10 Thunderbolt II's from the 355th Wing, assigned to Davis-Monthan Air Force Base, fly over Tucson area hospitals to honor healthcare personnel and first responders as they are some of the frontline workers dealing with the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) head on. "It's been an exhausting two to three months," says Campos, "it's pretty cool, I like how they're going by each hospital."

Tucson gets by during coronavirus pandemic

Updated

Two F-16 Fighting Falcons from Arizona Air National Guard’s 162nd Wing and two A-10 Thunderbolt II's from the 355th Wing, assigned to Davis-Monthan Air Force Base, fly over Northwest Medical Center north of Tucson on May 14, 2020.

Tucson gets by during coronavirus pandemic

Updated

A letter carrier portrait on the Ok Market building, located in the Armory Park neighborhood, is adorned with a face mask on May 18, 2020.

Tucson gets by during coronavirus pandemic

Updated

Rosemary Garcia waits for a family member outside of a store at Park Place Mall, 5870 E. Broadway Blvd., in Tucson, Ariz. on May 19, 2020. Malls reopened today under CDC guidelines and Gov. Ducey's new rules for businesses due to the Coronavirus pandemic. Park Place Mall has signs throughout the mall reminding customers to keep a six feet distance as well as hand sanitizer stations near each entrance. About half of the tables in the food court have been removed to allow for social distances as well as less than half of the stores have opened with new guidelines. Of the stores open, only 10 customers are allowed to shop in each store at a time.

Tucson gets by during coronavirus pandemic

Updated

Pat Schlote steams clothing before it is put on the sales floor at the Golden Goose Thrift Shop in Catalina, Ariz., on May 21, 2020.

Tucson gets by during coronavirus pandemic

Updated

Ada Contreras, teaching assistant, looks through containers while reorganizing toys at Herencia Guadalupana Lab School, 6740 S. in Tucson, Ariz. on May 21, 2020. As Child care centers begin to re-open when they are ready, Herencia Guadalupana Lab School is reorganizing and cleaning everything in the facility before re-opening on June 2. To allow for social distancing and decrease the amount of items children touch, Herencia Guadalupana Lab School has sheds where items will go as well as placing items in containers organized by category.

Tucson gets by during coronavirus pandemic

Updated

Jen Martinez, right, softball coach, teaches Skylar Reilly about hitting during a session at Centerfield Baseball Academy, 5120 S. Julian Dr., in Tucson, Ariz. on May 21, 2020. After re-opening on Monday, Centerfield Baseball Academy has implemented new policies in response to the Coronavirus Pandemic such as wearing masks, cleaning, signage, hand sanitizer and limiting the amount of people inside the facility.

Tucson gets by during coronavirus pandemic

Updated

Karl Bosma, left, and George Cantua, with facilities and maintenance, lay down stickers to mark six-foot separation distance around one of the baggage carousels, part of the efforts at Tucson International Airport to work within the restrictions of COVID19, May 22, 2020, Tucson, Ariz.

Tucson gets by during coronavirus pandemic

Updated

A lone passenger waits for a flight near one of the shuttered restaurants in the B Gates before Memorial Day at Tucson International Airport on May 22, 2020.

Tucson gets by during coronavirus pandemic

Updated

Drew Cooper on the stage in the St. Philip's Plaza courtyard, May 22, 2020, Tucson, Ariz., where live music is back on the schedule.

Tucson gets by during coronavirus pandemic

Updated

Many people visit Tumamoc Hill during the first day of Tumamoc's re-opening in Tucson, Ariz. on May 25, 2020. After being closed due to the Coronavirus pandemic, Tumamoc Hill re-opened with some modifications. There are hand sanitizer stations throughout the hike to the top as well as arrows, spaced 10-ft apart, lined up and down the hill. Some runners, hikers and walkers are also wearing masks during their hike. "The steps we are taking aim to provide our community with needed exercise, connection to our beautiful desert and a sense of comfort in such a trying time, while balancing the fact that gathering as a community endangers each of us and our loved ones. This is an unprecedented challenge that we are taking extremely seriously," said Benjamin T. Wilder, director of Tumamoc Hill. Visitors are also asked to limit their group to three people and to not touch the gate at the top of the hill- a tradition for some who make it to the top. "This is a time when we need to establish new traditions and adapt in a creative manner that embraces empathy, unity, care and patience," Wilder said.

Tucson gets by during coronavirus pandemic

Updated

Pen Macias, artist, works on part 2 of a mural for a client on E. Broadway Rd., between S. Columbus Blvd. and S. Alvernon Way, in Tucson, Ariz. on May 25, 2020. Macias, known as The Desert Pen, has been working on her clients mural for the past three months. "It's the one thing I love, I have a passion for and the only thing I could be happy doing," said Macias. The mural represents her client, a single mother of four who works in the health care field. One half of the mural is dedicated to the connection between mothers and their children. The other half is dedicated to the connection between nurses and patients. The client wanted some positivity in the mural to show how nurses give a piece of themselves to their patients hence the puzzle pieces in the nurse and the patients, said Macias.

Tucson gets by during coronavirus pandemic

Updated

Christina Cortinas, posing at her home, May 28, 2020, Tucson, Ariz., with a photo of her and her mother, Catherine Rodriguez, in San Diego, 1991. Rodriguez is currently in assisted living and fighting COVID19. Cortinas hasn't seen her mother in months, the longest such span in her life.

Tucson gets by during coronavirus pandemic

Updated

Ruben Lopez looks through handouts while attending a Eviction Resource Fair with his family outside the Pima County Justice Court.