Dave Foreman put words like biodiversity and extinction on the map.

The former Tucsonan launched two groundbreaking environmental movements: the radicalism, civil disobedience and “monkeywrenching” of Earth First in the 1980s, and the “rewilding” movement to protect massive blocks of nature for wildlife in the decades since then. Both movements proved influential, serving as a springboard for tree-sitting protests and land planning efforts that persist today, not least the Tucson area’s Sonoran Desert Conservation Plan.

Foreman, who died Monday, Sept. 19, at age 75, was among the first if not the first environmental leader to conclude species and landscapes were disappearing and more sweeping actions than previously contemplated were needed to reverse those trends.

“For outdoors people who saw animals and plants disappearing before their eyes and were frustrated by the environmental movement’s increasing reliance on lawyers rather than visionaries, Earth First’s message was a resounding one. By 1990, the anarchist group had attracted thousands of followers, from hippied-out misfits to college professors,” wrote Susan Zakin, a former Tucson writer and author of a history of that movement, in an essay posted the day after his death on her web magazine, Journal of the Plague Years.

“Dave Foreman changed the way we thought about our country and about nature. It’s not turning back the frontier and restoring Eden, but it’s still the best we have,” Zakin wrote.

Foreman died in his Albuquerque home after a several-months battle with a lung illness. He had remained involved in conservation issues until the end, advising groups such as the Rewildng Institute, which he founded as a think tank to develop longterm land conservation plans, said John Davis, the institute’s director and an associate of Foreman’s for 37 years. Foreman’s conservationist career spanned half a century.

But as a visionary, a “redneck wilderness advocate” and hell raiser, Foreman was regularly a target of sharp criticism. In the 1980s, he faced repeated charges of “eco-terrorism” — including from some mainstream environmentalists — for his advocacy of environmental “direct action,” going beyond civil disobedience and tree-sitting protests to tree-spiking, cutting down billboards and pouring sand into gas tanks of bulldozers, among other activities.

In the late 1980s, while living in Tucson, he faced federal felony charges and a high-profile prosecution that he led a plot to destroy power lines and damage nuclear power plants — charges leading to a plea deal that ultimately left only a misdemeanor conviction on his record.

In the 1990s and beyond, he faced accusations of racism due to his unstinting advocacy of immigration limits in the name of population control — charges he and his allies strongly denied.

Back in Foreman’s Earth First days, Outside magazine called him “arguably the most dangerous environmentalist in America.”

Longtime Tucson activist and former Earth Firster Kieran Suckling said last week that after spending a few years in other causes, “It was when I encountered Dave Foreman and Earth First that I really found a vision that made my heart sing.” Suckling and other founders of the Tucson-based Center for Biological Diversity all met as Earth Firsters.

“He was a great speaker, he was charismatic, he was bombastic, he was funny and he was deadly serious about the essential importance of wilderness and wildlife to the planet, and to human society, and calling people to defend them as the highest calling in life,” said Suckling, director of the Center for Biological Diversity.

The center came out of that vision, “because we came from there. This was our origin story. This is where we learned our values, where we learned to commit, to be uncompromising,” he said, although the center uses different tactics, such as litigation and lobbying.

Dave Foreman

‘Confessions of an Eco-Warrior’

Born in Albuquerque, Foreman was a fourth-generation New Mexican whose family had come west in Conestoga wagons, Zakin wrote.

First exposed to the wild as a Boy Scout, Foreman earned a bachelor’s degree from the University of New Mexico as a history major. In college in 1964, he supported arch-conservative Barry Goldwater for president and formed a UNM chapter of the conservative Young Americans Freedom. He joined the Marines after graduating during the Vietnam War, but was dishonorably discharged after a couple of months for going AWOL.

“Dave did not like to take orders,” his associate Davis said.

He stayed a registered Republican until 1980, when the election of anti-environmentalist Ronald Reagan as president convinced him Republicans were no longer interested in conservation, and he switched to the Democrats, Davis said.

Starting in 1973, he worked for the Wilderness Society, as a Southwest representative and later a Washington, D.C. lobbyist, working in an office three blocks from the White House. That job triggered his alienation from the mainstream environmental movement’s ethos of moderation and compromise.

His turning point was RARE II, a U.S. Forest Service exercise to determine which forest lands deserved wilderness protection. The service decided in 1979 to recommend protecting only 15 million of 80 million still-undeveloped forest lands.

“As I loosened my tie, propped my cowboy boots up on my desk and popped the top on another Stroh’s, I thought about RARE II and why it had gone so wrong,” Foreman wrote in his his 1991 book, “Confessions of an Eco-Warrior.”

Then-President Jimmy Carter was supposedly a great friend of wilderness and a former top Wilderness Society official was an assistant Agriculture secretary overseeing the Forest Service, he noted. “But we had lost to the timber, mining and cattle interests on every point. Moreover, damn it, we — the conservationists — had been moderate. The anti-environmental side had been extreme, radical, emotional, their arguments full of holes. We had provided more — and better — serious public comment.”

That and internal dissatisfactions with environmental groups led Foreman and four activist friends to pour out their frustrations on a trip to northern Sonora’s Pinacate Desert, later a national park. Then they drove to Foreman’s home in Glenwood, New Mexico, and, over a campfire, birthed the idea of forming Earth First.

Linda Lewis of Tucson, then conservation chair for the Sierra Club’s Grand Canyon chapter, accompanied them, and recalled Foreman’s gentleness and rage as he laid out his vision.

“We all revered Ed Abbey,” said Lewis, now Linda McNulty and board chair for the Tucson Audubon Society, speaking of the essayist-polemicist who authored “The Monkey Wrench Gang” about a group of eco-raiders plotting to blow up Glen Canyon Dam. “He had this romantic, fierce love of the West, and we revered that. Earth First was going to be the Ed Abbey Monkey Wrench Gang in real life.

“Dave called himself a radical but I can’t think of a word that really describes the compassion, the consideration, the feeling he had for the earth. It tore him apart when a bulldozer ripped through untouched wilderness, or a chainsaw tore down virgin forest. He felt the fight was worth having and he wasn’t afraid to have it.”

The group called itself Earth First to sum up organizers’ view “that in any decision, consideration for the health of the earth must come first,” Foreman wrote.

Attorney Gerry Spence, left, and activist David Foreman talked to reporters in this 1989 photo during the prosecution in Arizona of four environmentalists on felony charges they conspired to sabotage nuclear facilities in three southwestern states. Foreman eventually took a plea agreement that left him with a conviction of a single misdemeanor.

‘No compromise’

Earth First’s first public activity came in 1981, when activists used three 100-by-20-foot rolls of black plastic, 1,000 feet of duct tape, and 1,000 feet of nylon rope to create a simulated crack that they poured over the face of Glen Canyon Dam, a project they viewed as an unforgivable offense against the wild for having drowned pristine wildlife habitat to create a reservoir. That drew them a lot of publicity, and the number of adherents grew quickly.

One was Paul Hirt while he was a University of Arizona student from 1981 to 1992. He found refreshing Earth First’s motto of “no compromise in defense of Mother Earth,” recalled Hirt, now an Arizona State University professor emeritus of history.

“If you are fighting environmental battles on a daily basis, you are usually losing. About all you can do is try to get some minor mitigations or compromises. It is demoralizing; you’re just slowing the destruction,” Hirt said. “When an environmental organization comes along and says ‘we are going to stop talking about compromise, about half a loaf, we are going to say in a moral sense, a scientific sense, what do we need to do to save nature’, it was freeing, it was energizing.”

Through the ‘80s, Earth First’s popularity mushroomed. It promoted a philosophy called “deep ecology,” also known as ecocentrism, said a 2018 book of that title.

“Ecocentric thought assumed that trees, bears, fish and grasshoppers should receive as much consideration as humans in decisions large and small about the shape of modern society,” wrote author Keith Woodhouse, a Northwestern University history professor.

From bottom to top: Margaret Katherine Millett, Mark Leslie Davis and David Foreman were escorted in irons from the U.S. Federal Court building in Phoenix on June 3, 1989 after they were arrested in an alleged conspiracy to sabotage nuclear facilities. Foreman eventually took a plea agreement that left him with a conviction on a single misdemeanor in the case.

High-profile prosecution

By blockading roads, sitting in old-growth trees, filing appeals of timber sales and other steps, they stopped some timber sales in the Pacific Northwest, a gas-drilling project in Wyoming, and, temporarily, an oil drilling project in New Mexico. In one day in 1988, they held rallies, road blockades and other forms of protests at close to 100 sites across the country. Woodhouse’s book argued that between Earth First and more conventional environmental protests, the Forest Service “slowly reined in its emphasis on industrial production” or timber-cutting.

The group won hundreds if not thousands of individual victories through various tactics, but “the most important thing is that Earth First did what it was designed to do: shake up the environmental movement and give it some backbone,” said Todd Schulke, a Center for Biological Diversity co-founder who was previously an Earth Firster. A key victory was when Earth First and others’ efforts saved thousands of Northern California redwoods that would have been logged, Schulke said.

Tree spiking, however, proved controversial enough that eventually, Foreman himself wrote that it was time to at least reconsider it. One injury to a logger was documented from tree spiking — a 1987 Northern California incident in which a logger’s blade struck an 11-inch nail that had been driven into a log, causing a huge section of blade to fly off its track and hit 23-year-old George Alexander in the face. The blade tore his left cheek, cut through his jawbone, knocked out teeth and nearly severed his jugular vein, the Los Angeles Times reported.

But the incident was never linked to Earth First, which took pains to always notify logging companies when it had spiked a tree, to discourage efforts to cut it, the group said.

The group eventually fractured on two fronts, however. First, in 1989, the FBI arrested Foreman and four Earth First colleagues, accusing them of attempting to use a cutting torch to destroy a power line tower feeding energy for a pump station for the Central Arizona Project. They were also prosecuted for earlier damage to power poles supporting power lines that fed two uranium mines and for cutting ski-lift poles at a ski resort near Flagstaff on land the Navajo and Hopi tribes consider sacred.

Foreman and others were charged with various crimes. Prosecutors alleged the action against the CAP pump station was a prelude to future efforts to topple power lines to the Palo Verde nuclear plant near Phoenix and the Diablo Canyon nuclear plant in central California, along with the Rocky Flats nuclear weapons facility near Denver. It turned out as well that one of the alleged plotters was an undercover federal agent who had infiltrated the group for more than a year, Woodhouse wrote.

Most of those arrested other than Foreman had formed a separate but related group from Earth First. While the others charged received prison sentences of one month to six years, Foreman was able to plead guilty to a misdemeanor after serving five years of probation and wasn’t imprisoned.

Woodhouse said his detailed research into the group turned up no evidence that Foreman was actually involved in any plot to destroy power lines or nuclear plants.

Nevertheless, the FBI sting helped prompt Foreman to leave Earth First by 1991, Davis said.

The other factor driving Foreman from Earth First was a growing internal split between him and others who stuck to the group’s founding principle of deep ecology and those who favored infusing the group’s mission with more social justice activities including feminism and crusades for economic justice for nonwhites and the poor in general.

Foreman’s view was “those things are laudable goals, but they’re not what we’re focused on. While those issues need support, those are distinct issues needing their own groups,” Davis said.

‘The big wild’

Foreman co-founded the Wildlands Network in 1991, which aims to establish a network of protected wilderness areas across North America. He served on the Sierra Club board of directors for a time in the 1990s, but left after a dispute over immigration issues.

In the early 2000s, he co-founded the Rewilding Institute. Its website says it seeks to promote “the integration of traditional wildlife and wildlands conservation with conservation biology to advance landscape-scale conservation.”

“It was a whole new powerful movement like Earth First, this idea it’s essential we protect big wildland spaces and that we need to go into every bioregion in the country and map out a connective network of the big wild,” Suckling said. “What Dave created was not an organization. Dave was creating ideas and movements.”

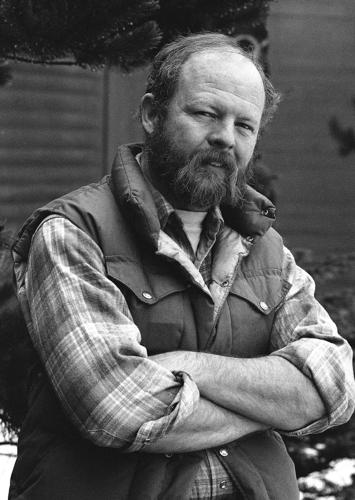

David Foreman, founder of "Earth First," in Juneau, Alaska, March 10, 1988.

Foreman’s biggest conservation legacy was helping other conservationists realize it’s not enough to save small, isolated parcels of wildland, Davis said. “We need to connect big wild areas, thinking big in terms of large cores, wildlife corridors, top predators,” Davis said.

Some specific areas in the Southwest and in the Northern Rockies have been protected due to Foreman’s recent efforts.The broader vision of a continuous corridor “will be the work of decades and even centuries,” Davis said.

Divided by immigration views

Foreman’s stance opposing immigration drew harsh criticism even from some environmental allies. Although he spoke out on this issue for many years, his views crystallized in the book Man Swarm, published in 2012, that called for immigration limits to curb U.S. population growth that he wrote could double the number of this country’s inhabitants in a century.

Overpopulation “is the main driver of the extinction of many kinds of wildlife, the wrecking and taming of wildlands and wild waters, and the creation of pollution, including carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases,” he wrote.

Foreman advocated limiting immigration to the number of U.S. residents who leave the country each year, a policy that the Sierra Club had adopted in 1989 but rescinded in the 1990s after drawing huge protests.

Foreman's view was that immigrants from less developed countries would improve their living standards to at least approach those of existing U.S. residents, thereby ratcheting up this country's pressure on land, water, wildlife and the climate.

Foreman wrote, “We’re being an overflow pond for reckless overbreeding in Central America and Mexico (and for the Philippines and Africa and . . .). So long as we offer that overflow pond, there is less need to lower birth rates in those countries.” He noted the World Bank reported Guatemala’s fertility rate for women in 2012 was 3.8 children, far above U.S. levels.

"If we quit being the relief valve for the baby swarm in Guatemala, births would have to come down," Foreman wrote.

Suckling, Davis and Myles Traphagen of the Wildlands Project all disagreed strongly with Foreman’s immigration stance, but said they never thought he was racist.

“But he refused to deal with the racist implications of his plans for stopping immigration,” Suckling said.

Of Foreman’s Guatemala statements, Davis said, “Dave should have realized that those words would have been construed as racist, and he should have tempered his language there. Those words come across as callous, but he would have been at least as callous in talking about white people who have big families.”

Overall, Foreman’s major emphasis was on the problem of overpopulation, not immigration, and he was far more critical of the environmental impacts of affluent U.S. residents than of Latin Americans, Davis said.

Foreman also believed the U.S. needed to deal with economic and political pressures in Latin countries that were driving immigration. He also was outspokenly opposed to building a border wall, and once chided Traphagen and other younger environmentalists for not being willing to lay their bodies down to stop its construction, Traphagen said.

‘That’s racism’

But Sergio Avila, a Sierra Club activist, particularly took issue with Suckling’s view, saying, “It’s very likely that Kieran doesn’t feel racism the way Indigenous people at the border feel racism. It’s very likely that these people live in a bubble that doesn’t allow them to see it. It’s in the writings,” he said of Foreman. “That’s racism. It’s not an opinion. It’s a fact.”

Depriving Latino people south of the border from coming here and improving themselves is racist, Avila said. “What if people coming here, bringing a different perspective on how to address climate, water management, production of food” improve things, he asked.

Avila himself came here in 2003 as a legal immigrant from Mexico “to contribute, and I have contributed to these organizations binationally for 20 years.” Besides the Sierra Club, Avila also has worked for Sky Island Alliance and the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum as a biologist.

Avila also took issue with some of Foreman’s other environmental stances. While the Rewilding Institute say it won’t remove people to restore damaged landscapes, Avila contends such activities often ignore the social and cultural histories of people, particularly Indigenous people, who had lived there before.

Looking at both sides, author Keith Woodhouse first praised Earth First’s early emphasis on imperiled species and landscape protection, and noted the questions the group wrestled with about direct action and the limits of conventional environmental politics are the same questions the climate movement confronts today. Also, many ideas Foreman and his allies pushed for that were considered fringe, such as curtailing logging and dam removal, are now in place or being actively discussed today, he said.

As for tree spiking, “I think it hurt Earth First. It was one of the things that led to the schism in Earth First. It was not a productive strategy,” Woodhouse said.

He also thought it a mistake for Foreman to sideline social issues and act as if they were completely separate from environmental issues when they weren’t, he said.

“I consider Earth First to be an important part in the history of conservation in the U.S. and an important influence, warts and all, on modern environmentalism,” he said.