It seemed to come out of nowhere.

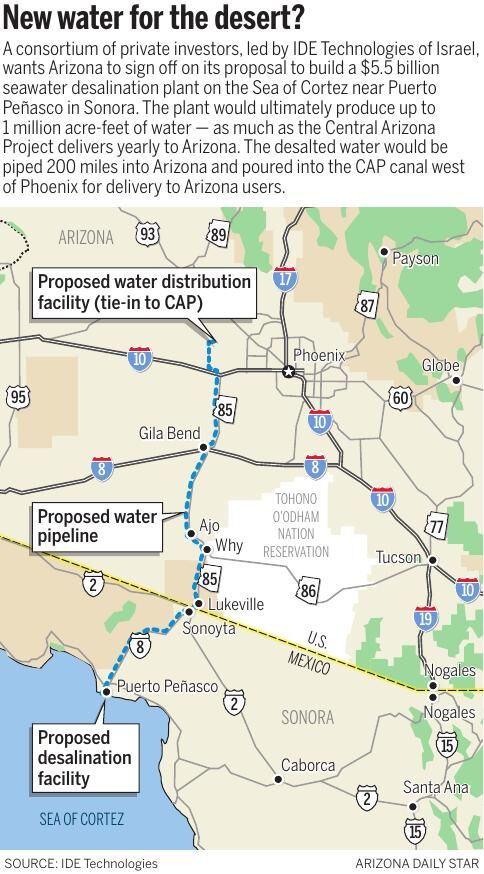

A proposal for a $5.5 billion desalination plant on the Sonoran coast that few non-insiders had even heard of a month ago is now moving through Arizona government at a pace many find too rushed but others welcome.

A state water board gave its staff approval to start discussing the proposal with the project’s main Israeli proponent, even though the new board lacks criteria for how it will judge such ideas. The proposal is stirring accusations of backroom dealing, while its backers are pushing it as a major fix for the state’s water crisis.

From a public standpoint, it all started the evening of Dec. 11, when David Beckham, chairman of the Water Infrastructure Financing Authority of Arizona governing board, received an email from Jordan Rose. She’s a Scottsdale attorney who represents an Israeli firm looking to build the desalination plant in Puerto Peñasco, Sonora, along the Sea of Cortez, Beckham said later.

“Please see the enclosed application. Let me know the next steps,” Beckham said Rose emailed him.

The application was for what Rose called “an innovative and transformative project that will supply the State of Arizona with a new assured water supply.” It said the plant would desalinate at least five times more water than any such plant in the world.

Beckham said he told Rose on Dec. 13 he wanted to put off considering the plant until after the board hires an executive director, which was expected to occur by the end of the next week. Then, he said he told Rose, the board would review the application “promptly.”

He changed his mind later that day after receiving a phone call from Sandra Watson, president and CEO of the Arizona Commerce Authority, asking that the board take up the proposal the following week, before Christmas, because there was “urgency involved,” Beckham told the authority’s Long-Term Water Augmentation committee on Dec. 16.

That call led Beckham to schedule meetings on the proposal before the committee that day and before the full board on Dec. 20. The latter day, after five hours of debate, the water board’s nine voting members unanimously agreed to start discussions with Israeli-based IDE Technologies, to see if an agreement could be struck for terms under which such a plant could be built with private money, with the authority serving as a financial backstop.

The company has asked the authority to put $750 million of $1 billion the Arizona Legislature appropriated for water augmentation projects into escrow, presumably to be drawn upon if IDE can’t sell enough of the high-cost, desalinated water to cities and farms. IDE is looking for what its officials call a long-term commitment from one or more public entities to someday purchase the water.

In works several years, firm says

Seawater desalination plants are viewed by many, including Republican Gov. Doug Ducey — who will be succeeded by Democrat Katie Hobbs on Jan. 2 — as an unlimited water source and a key water solution. But they have drawn intense criticism for their high construction price tags and possible environmental effects.

Many people active in water issues say Arizona has already waited too long to pursue a desalination plant, a topic that’s been on and off the table for decades. Others say the state should focus on less expensive options first, such as wastewater recycling as well as conservation, and that desalination would promote otherwise unsustainable growth without requiring any basic changes in how Arizona uses water.

At the Dec. 20 meeting, several environmentalists expressed deep concerns about the possible impacts of more saline wastewater discharges from the plant after the seawater has been desalinated. Company officials sought to assure the infrastructure board that there will be “zero” impacts.

But by far the most heated issue is the speed with which the proposal has moved, raising concerns of a backroom deal.

IDE officials told the board and a legislative hearing that came afterward that it’s been working on this proposal for three to four years.

“We have met with the governor of Arizona Doug Ducey, Senator (Mark) Kelly, Senator (Krysten) Sinema, (former Arizona) Senator Jon Kyl, the Arizona Commerce Authority, the Department of Interior, the Arizona Department of Water Resources, with the Central Arizona Project, with the speaker of the House, the sirector of transportation, the director of environmental quality, with the BLM, with the National Park Service, the Bureau of Reclamation, with the governor’s policy adviser, with the U.S. Air Force, with the Fish and Wildlife Service and with the Salt River Project,” a top IDE official, Erez Hoter Ishay, told the legislative hearing.

Company officials have also met with officials of municipalities including Tucson, Pinal County officials and those from the private Arizona Water Company and Epcor water companies, he said.

‘Isn’t passing the sniff test’

But word of this proposal didn't reach several prominent critics of it, as well as numerous legislators, until at most five days before the water authority board's Dec. 20 approval of its resolution to start formal discussions with IDE.

At a two-and-a-half-hour Joint Legislative Water Committee meeting that immediately followed the water board vote, legislators in both parties recalled that when they approved a bill in spring 2022 appropriating $1 billion for augmentation, they inserted safeguards to reduce the possibility an inside deal would be cut.

They said they were assured by backers of the proposed legislation that no such deal was in the works. Now, it appears that it was, said several Democratic legislators.

Outgoing State Senate President Karen Fann, a Prescott Republican, told that hearing, “This might be an excellent project; it could be the best thing since sliced bread. I think I spoke for many of you, if not most, when I said we don’t want the legislative body committing anything in the way of financial resources at this time, until we see everything is vetted and we know all the details. Then the legislative body will be glad to give our blessing to it.”

Rep. Reginald Bolding, a Phoenix Democrat, said while he thinks people ultimately will be excited about the project’s possibilities, “it is unfortunate that the process has tainted a cloud over the project itself.”

During the past legislative session, “we were able to pass a historic bipartisan package” for the $1 billion appropriation, “but since the bill was signed nothing was heard. We had whiplash from the Friday meeting to the Tuesday meeting,” said Rep. Andres Cano, a Tucson Democrat.

“The only thing I have to say is that that thing isn’t passing the sniff test right now,” said Cano.

He, Bolding and Fann, along with outgoing Republican House Speaker Rusty Bowers who supports the project, are non-voting water authority board members.

While two board members, including Bowers, had discussed this project or some kind of project confidentially with IDE before, authority board members and backers of the plant say the board’s Dec. 20 vote was not the result of a backroom deal. It only marked a starting point for prolonged discussions leading to formal negotiations for an agreement over what kind of help the state would give the proposal, they said.

“We need to move forward, exploring and vetting ... We’re not putting the state at risk. We’re just starting a conversation. We’ve hit it with the right balance. We’re moving forward without binding us,” board chairman Beckham said.

‘Game-changer for Arizona’s future’

In a statement to the Star, the Commerce Authority said Watson, as Arizona’s lead economic development director, has been in discussions for many years about possible water augmentation projects, including this one.

Watson told Beckham in mid-December about IDE’s timeline as it relates to an upcoming federal review, for which IDE submitted a formal application to the U.S. Bureau of Land Management the day after the water board vote. Company officials said at the board meeting that the project will likely require a full environmental impact statement.

“The project is a game-changer for Arizona’s future, with the potential to deliver over 1 million acre-feet of water a year. The project has undergone numerous years of planning and preparation,” the Commerce Authority said.

Company attorney Rose cited IDE’s plan to file for the federal environmental review on Dec. 21 as a key reason it wanted a favorable vote from the state water authority. As the water authority had just started cranking up work in the past few weeks on augmentation projects, “this was the first opportunity they had to engage with the newly formed group,” Rose said of company officials.

Company officials were “grateful” to submit their proposal to BLM for that review with the board resolution in hand supporting “further conversations with the state,” Rose said.

“This is an urgent situation. We’re pleased that (the water authority) is moving urgently to address it. There is an imperative to move quickly, to address the water situation Arizona is facing,” said C.J. Karamargin, spokesman for Ducey, a supporter of this project and desalination in general.

“No one should be surprised when the governor stood in the House chamber at the beginning of the legislative session, and laid out his broad goal of what he would like to see with water,” including a big desalination plant, Karamargin said. “Karen Fann was sitting right behind him.”

This May 2, 2019 photo shows the inside of a desalination plant, where brine passes through tubes with coiled membranes to make water drinkable, in El Paso.

Piped to Southern Arizona

The plant is proposed by a consortium of companies, including IDE and Goldman Sachs, that calls itself the Arizona Water Solution Team. Company officials haven’t released names of other participants.

The plant would be entirely different from most desalination proposals discussed in Arizona to date.

Those proposals call for Arizona to pay for building one or more plants along the Sea of Cortez, then give all the water to Mexican cities and farmers. In return, Arizona could draw from Mexico’s Colorado River supplies.

This proposal is also far more expansive in other ways. For example, a still-pending proposal, that’s had extensive study sponsored by the Central Arizona Project and 17 other entities, mainly federal and state agencies in both countries, calls for building two plants along the Mexican coast, producing 200,000 acre-feet a year.

The newly proposed plant would start with around 350,000 acre-feet and gradually escalate to a million. It would bring desalted water north to Arizona via a 200-mile-long pipeline, ending west of Phoenix. There, the water would be transferred to the Central Arizona Project canal for delivery to cities and farms from the Phoenix area southeast to Tucson.

Then the new project would build a much smaller pipeline to take some of the desalted water from Tucson south to Nogales. Some of that piped water also could be delivered to other cities and towns in Southern Arizona with water needs, IDE officials told the water infrastructure board Dec. 20.

This plan’s backers have a much more ambitious timetable than many experts including state water officials have said is likely for a big desalination project — at least 10 years to get permitted and built. The U.S.’s largest plant, in Carlsbad, California, near San Diego, which IDE operates, consumed 15 years of debate and planning before water started being delivered in 2015.

IDE officials, however, told the water infrastructure board they want to streamline their process to get permitted in two years and have water flowing by 2027.

At the legislative hearing, board attorney Brett Johnson acknowledged the IDE’s stated need to expedite the process triggered the board’s action to get the discussions started.

“If there is a showing or need to expedite the process, especially to allow the staff to engage ... That will definitely lead to an expedited process,” he said.

‘Financial stability of project is sound’

In its proposal to the state, IDE says that with Arizona state government currently completing a statewide water supply and demand assessment, it’s not possible to provide a complete analysis of what cities or other entities would benefit from this project.

“However, what we do know is with the current and anticipated future reduction of Colorado River water supplies, Arizona is losing control of its water future. There is an immediate and existing need for dependable water supplies within the (Central Arizona Project) service area. There are also other existing, near-term, and long-term water demands in Arizona that cannot be satisfied by existing water supplies,” the company’s proposal said.

“As this project has the ability to provide an assured water supply with enough capacity to supply the entire state, the financial stability of the project is sound and, while it has significant capital needs, applicant is confident that meeting these capital needs is very feasible.”

Those assurances are greeted skeptically by Arizona State University water researcher Kathleen Ferris, a former director of the Arizona Department of Water Resources and the Arizona Municipal Water Users Association. She and other critics of the water board’s action noted that the board was just given extensive new authority over these projects by the legislation that appropriated the $1 billion.

“What appears clear is that the IDE project was shopped around long before the (2022 water augmentation) legislation passed and long before the WIFA (Water Infrastructure Financing Authority) board members were appointed,” she told the Star. “The Legislature and the public deserve more.”

Not only has the state not finished its water supply and demand analysis, the water authority board still hasn’t developed policies for how it will assess such projects or for basic procurement activities, she noted. It only hired an executive director on Dec. 20.

“I’m concerned that this is moving so fast and that no one has taken the time necessary to really insure that this is a sound proposal,” Ferris said. “I don’t care what IDE’s timeline is. The state of Arizona should be driving this.”

A view of the older AES Huntington Beach Power Station in Huntington Beach, California at left, and new one at right, and the proposed site of the Poseidon Desalination Plant, which would draw ocean water through an existing intake pipe.

‘Reeks of backroom deals’

Harsher words still come from Sen. Lisa Otondo, a Yuma Democrat who, like Fann, is leaving the Legislature. She told the legislative hearing the speed at which the project is moving “is completely irresponsible,” shows “an utter lack of transparency” and “reeks of backroom deals.”

Otondo told the Star she “felt really angry” because she learned of the desalination plant proposal only a few days before the water board voted on it. She called the presentation company officials made to the legislative committee “more of an advertisement” and “a dog and pony show.”

She criticized IDE's 46-page, written proposal for lacking any detailed analysis of the project’s economics or environmental impacts — the kind of analysis legislators had required of such projects when they drafted the augmentation bill last spring.

One issue where she particularly feels transparency is lacking is the water’s price for cities.

“This water will cost at a minimum $3,000 per acre-foot,” she said. IDE officials pegged the cost at $2,200 to 3,300, but Otondo said the ultimate figure will be at the higher end, “according to everyone in the water industry I have spoken to.”

It now costs cities $240 an acre-foot to buy CAP water, and could cost $400 by 2028. Otondo is concerned the state will be left holding the bag for whatever money cities and other users don’t want to pony up to repay the construction cost.

Since $3,000 an acre-foot totals a $3 billion annual price tag for a million acre-feet, “what group of water users is going to pay $3 billion? ... I can tell you from my experience that even $2,400 an acre-foot of water is simply untouchable for most if not all municipalities.”

Questioning Arizona Department of Water Resources Director Tom Buschatzke, Otondo noted that when Yuma-area farmers asked the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation this year to pay them $1,500 an acre-foot to give up some of their Colorado River supplies, their request was rejected as excessive, as was a similar request by Imperial Valley farmers in Southern California.

“With your expertise, do you know of any municipality that can pay over and above $2,400 per acre-foot for any water?” Otondo asked.

“I’m not aware of any municipality doing that now. Looking in the future, we all know that in this water crisis on the Colorado River,” if developers want to continue to build homes, they will pay whatever price it’s worth to them, Buschatzke replied.

His department hasn’t issued any determinations of 100-year, assured water supplies — as state law requires — for new subdivisions in Pinal County since 2013, he noted.

“I don’t think I can say $2,400 is too much. It all depends on what the housing is, and whatever economic growth you want to have in that area,” he said.

IDE’s Hoter Ishay, the project’s team leader, told the water authority board, “No one can value the cost of water. When you don’t have the water, you don’t have money.”

Before Israel moved big-time into desalination, “The Sea of Galilee was almost to dead pool,” said Hoter Ishay, referring to the second lowest elevation water body on earth and Israel’s largest lake. “Now, it’s full,” with up to 90% of the country’s water coming from desalination plants, he said.

In an interview after the hearing, Otondo said the state needs to look closely at all options for new water supplies before acting, but it sounds now "very much like this is a priority moving forward. When we wrote the legislation, it’s why we said, 'There must be assessments, reports, and priorities.' Now, the Legislature has to go back and tighten up some of this stuff."

Busschatzke took a different tone at the hearing when Otondo asked if he thought the water authority staff has the expertise to evaluate projects like this.

“Would it be fair for me to say it does not yet?” she asked.

Buschatzke replied, “If you’re talking about the staff, I would agree. There are members of the board who have expertise. I have it as a non-voting member. CAP General Manager Ted Cooke (a voting member of the board) is another one that comes to mind. At the staff level, they need more expertise.”

Nondisclosure agreements

Otondo also asked water authority attorney Johnson how many board members had signed nondisclosure agreements with IDE to discuss the project confidentially, adding, “My demand is for more transparency and more accountability from this body,” meaning the infrastructure authority board.

“I don’t know,” Johnson replied. “What I can assure you today is that the WIFA agency does not have any confidentiality or NDA agreements with IDE or any other proposer for that matter. There is a process for that. It has to go through legal review. It has not happened. I cannot speak for individual directors (of the board).”

Cooke, the CAP general manager, told the legislative hearing his agency had signed such an agreement with IDE to discuss some technical issues about the project. Hoter Ishay told the legislative committee the company had no such agreement with voting board members, but it has had such agreements with various municipalities. He didn’t name them.

Summing up, Otondo told Buschatzke she doesn’t think the project has been properly vetted. “The important question we always ask about water projects is ‘where is the water going, how much does it cost and does it meet the priorities of the state’. It’s not been answered.”

Buschatzke, saying he hadn’t signed a nondisclosure agreement, added he thought “there was an expectation, both here in the Legislature and with stakeholders, that helped get the (water augmentation) legislation over the line, that there would be transparency.” The water authority’s newly passed resolution “giving staff support and direction for going out and doing due diligence ... there is an opportunity for continued transparency of that,” he said.

Bowers, the House speaker who leaves office this weekend, said, “I love the backroom deals, especially when they don’t happen.”

Speaking of the specific proposal submitted by IDE to the water authority board, he said, “The fact is, we didn’t like it, we disagreed with it, set it aside and created a proposal that we reviewed today and amended today, to make sure the state of Arizona had its upside protected, to participate in a privately funded operation.

“The untreated water is cleaner than Colorado River supply water,” Bowers said. “The price per acre-foot is not locked in any stone.”

The Central Arizona Project is a 336-mile canal in Arizona that supplies Colorado River water for the Phoenix and Tucson area, agriculture and several Native-American tribes. Construction began in 1973 and was substantially complete by 1994. This portion is located near Sandario Road and Mile Wide Road west of Tucson on March 17, 2021. Video by: Mamta Popat / Arizona Daily Star