This week’s big pulse of water into the long-parched Colorado River Delta will be one of the most studied water releases ever.

The University of Arizona, the United States Geological Survey, the Autonomous University of Baja California (UABC for short), the Sonoran Institute, the Nature Conservancy and the Mexican conservation group ProNatura will have monitoring teams in the delta running south from the U.S. Mexican border. They’ll have five years to see how the water affects the water table, the river’s hydrology, trees, shrubs, birds and seedlings.

The water, enough to serve 35,000 to 50,000 Tucson homes, is being released from Morelos Dam at the border under an agreement between the U.S. and Mexican governments that also involved Colorado River Basin states, irrigation districts, water agencies and conservation groups.

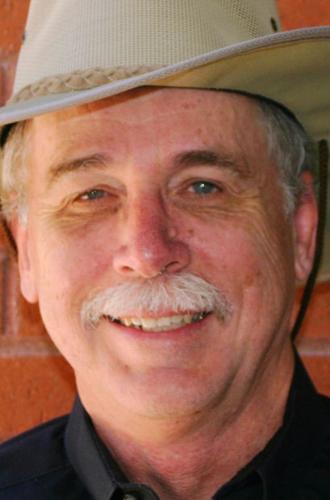

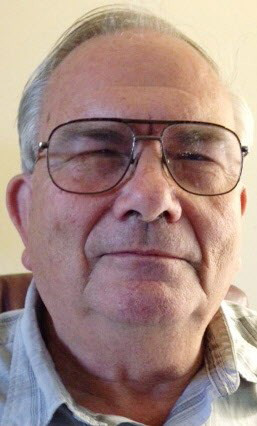

Two UA researchers who will be closely monitoring the release have deep roots in this remote region. The delta has been central to the work of both Geosciences Prof. Karl Flessa, now 67, and Soil, Water and Environmental Science Prof. Edward Glenn, 66, since the early 1990s. But, as a sign of the area’s vastness and remoteness, they didn’t even know one another until 2001.

This week, Flessa will be at the scene, as co-chief scientist for planning and coordination of the entire monitoring effort. Glenn will stay put, observing satellite images of the trees and shrubs at the Environmental Research Laboratory headquarters near Tucson International Airport.

Recently, they discussed their attachment to and their research at the delta.

Why have you devoted so much of your work there?

Glenn: When I started, we got to cruise around in a 4-wheel-drive vehicle, get stuck in the mud and see exotic places. It was for the adventure. That’s why anybody goes to the delta, for the adventure.

Flessa: It was just a fascinating place, an absolutely fascinating place. There’s this whole landscape that’s been converted for human use. There’s this enormous river that used to be controlled by seasonal climactic variations. Now, it’s controlled by society. That’s where you see all the effects of water management pretty dramatically.

Talk about some of your early research.

Flessa: I’ve been involved there since 1992. I was studying the estuary, the uppermost Gulf of California, where the Colorado River water mixes with the gulf water. I was examining the productivity of the upper gulf, working with clamshells as records of "pre-Dambrian" environments (a play on the ancient, geologic, pre-Cambrian era, he was talking about records dating back to the time Hoover Dam was finished in 1936 and 1,000 years earlier). Then, I got involved with students of mine, looking at the life history of fish in "pre-Dambrian" environments.

Glenn: I was there in 1993, when there was water in the river due to heavy rains. The federal government had released water into the river because the Wellton-Mohawk irrigation canal near Yuma was breached. There were trees all over the riparian zone along the river, not continuous trees, but you could see a nice ecosystem, with cottonwoods and willows and pockets of wetlands where the water had accumulated.

Then, we got a grant from NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration) in 1996 to use remote, satellite sensing to study the riparian corridor. It just happened to be when all those floods were going, in 1997-98-99 and 2000. We found that every year that there was a pulse flood, large or small, we found new regeneration of cottonwoods and willows plus wetland areas. We used tree ring data to do a whole chronology of what each flood did from 1983 to 2000, and then kept following it until 2008. After the floods stopped and the drought came, the number of trees and birds went into a real slow decline. (But) they didn’t just collapse. There is still lots of good habitat down there. We decided it was a really resilient ecosystem.

What specifically will you be doing this go-round?

Glenn: I’m part of the remote sensing, vegetation monitoring team. I’m going to be looking on satellite images for greenery, and the ground teams will be looking for how many trees will come up. Osvel Hinojosa, director of ProNatura’s water and wetlands program, will be monitoring birds, four times a year.

Flessa: I will be going from just south of Morelos Dam at the U.S.-Mexican border to as far south as the last crossing of the river, 40 river miles, not all the way to the Gulf of California. I’ll be there at least until April 3, although the pulse release will go until May 18.

The UABC, the UA and the USGS will be working down there, measuring surface flow, the response of the groundwater and the response of vegetation and wildlife, principally birds, for five years. There’s been good monitoring in the past based on remote sensing.

What will this research accomplish?

Glenn: The vegetation team will have a really good handle for the effect on the ecosystem. The hydrologists will … want to know how much water makes it downstream and how much gets absorbed into the deep groundwater and is not available for use by trees. The ultimate plan is to integrate the ecology models with hydrology ones, so when we plan the next release, we’ll know exactly how much water to ask for and when you need it.

Flessa: One thing we want to do is figure out where are parts of the river where it will be easiest to restore some of those riparian habitats. … In urban settings, we want to get people to use water efficiently. In agriculture, we try to get water used efficiently. In restoration, we have to do it the same way. The days of putting water back into the river and just expecting things to happen are over.

We have to figure out the best time to release the water, the rates of release, the quality of the water, the best place in the riverbed to release the water.

Will this experiment work?

Flessa: We can expect some surface water flow, but we don’t know if it will get all the way to the Gulf of California. We can expect some overbank flooding, which is important to the seedlings of cottonwoods. We know we’ll get cottonwoods and willows to germinate, but we don’t know how many will survive the first summer. We know we’ll recharge the groundwater. We don’t know how much … what Ed’s studies have shown and the Sonoran institute’s Francisco Zamora’s studies have shown is that a little bit of water goes a long way.

Glenn: Year one, we expect to see a really significant greenup in vegetation within two to three weeks of the release. I would predict there would be a good year for birds after that. At the end of four years, the trees will be 35 or more feet high. They grow pretty quick.

But there are people in the hydrology community who are saying the water won’t make it past reach 3, at the southern international boundary with Mexico, to 35 kilometers south of that. They are worried that a lot of the water will get absorbed up there and not get down to the intertidal zone to refresh the shrimp further south. But I’ve looked at every set of satellite images from the past, from every single release in that data record, and even a flow in April 2010 that was not high in volume, that made it nearly to the top of the intertidal zone. That release was tiny compared to what this is.

This release and the agreement authorizing it, known as Minute 319, covers a five-year period. What are the odds of this agreement being renewed and more releases happening in the future?

Glenn: If a shortage on the river is declared, all bets are off. With a dry year this year, they would have considered not releasing the water, because there is no firm commitment to doing it in a particular year.