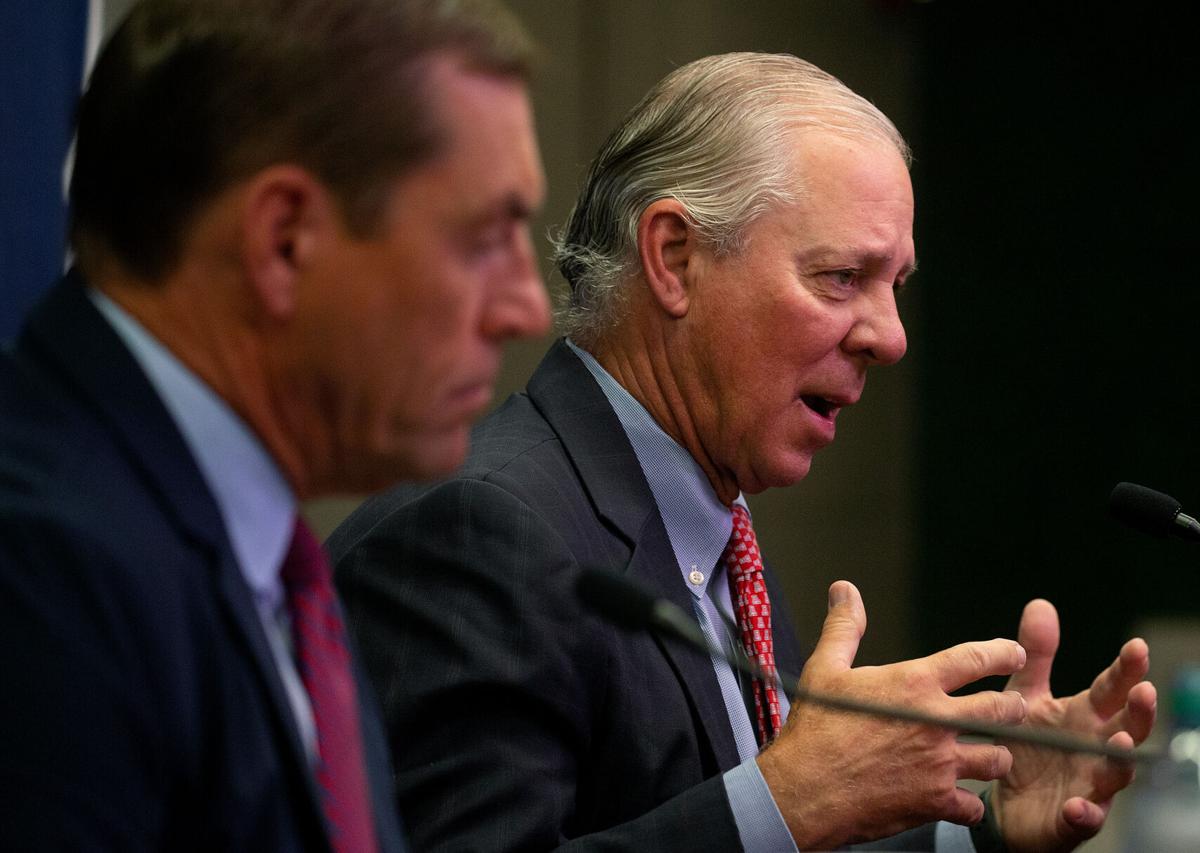

University of Arizona President Robert Robbins said he is considering cutting multiple sports programs after admitting to a $240 million miscalculation leading to a campus-wide “financial crisis.”

As Robbins looks for ways to balance the UA’s operating budget, he has pointed out that the athletics department at the university is running on a deficit and unable to support itself independently.

“Everything is on the table in terms of dealing with athletics,” Robbins told university faculty at a meeting last week. “This is an issue that is going to require a lot of tough decisions.”

One noted expert concurs.

“Cutting sports is one of the most difficult things that any athletic director or president can do,” said Karen Weaver, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania who studies the intersection of higher education and athletics. “Because some of the most loyal and dedicated alumni are former student athletes.”

Weaver has studied athletics in higher education for 40 years and said the UA is not alone in supporting a financially flailing athletic department.

“It’s true (at other universities) for a whole host of reasons, not the least of which depends on media-rights revenues,” she said. “Those revenues highly vary from conference to conference and school to school.”

The UA is switching from the Pac-12 to the Big 12 next year in an effort to “stabilize their revenues” after media-rights negotiations in the Pac-12 fell apart, Weaver said.

There have been other efforts to provide a cash infusion for UA sports. During the COVID-19 pandemic, much to the chagrin of many faculty members, Robbins authorized a $55 million loan from the university’s operating budget to the athletic department. The athletics department has not been able to repay that loan, Robbins said, which is part of the reason why the university has begun to struggle financially.

The university currently supports 23 sports programs, though the average number of teams at Big 12 schools is 17, Robbins said.

According to public data from the Knight-Newhouse College Athletics Database, the UA athletic department’s total expenses in 2022 were $124.94 million.

Of that, $35,174,017 was spent on facilities and equipment, $22,395,123 was paid to coaches, $19,996,951 was spent on support and administration compensation with severance, $14,101,997 was spent on game expenses and travel and $13,829,484 paid for athletic student aid.

An additional $2,594,234 went to recruiting costs, $1,144,200 went to medical expenses, and $1,842,910 went to competition guarantees. The remaining $13,866,010 paid for what the organization calls “other expenses,” including uniforms and marketing, for example.

In last week’s Faculty Senate meeting, Robbins said the athletic department’s budget was roughly $100 million, or about $24 million below what the Knight-Newhouse College Athletics Database reported. He said that about $40 million of that comes from the Pac-12, about $30 million comes from ticket sales, “primarily in football and basketball,” and the last $30 million comes from philanthropy and contracts.

According to the Knight-Newhouse data, the UA athletic department made $124.35 million in revenue in 2022.

Robbins hasn’t yet shared what sports programs he is planning on reducing or eliminating (the university’s full plan is due to the Arizona Board of Regents by Dec. 15), but they will most likely be men’s sports to adhere to Title IX guidelines. And they almost certainly won’t be the football or men’s basketball programs, which bring in most of the ticket-sales revenue the university sees.

Weaver said that for college athletes, it can be emotional to learn their program has been cut.

“They spend a lot of time and energy competing and representing the university,” she said. “To find out that the university can’t sustain their program is devastating.”

The UA would not be the first major university to cut sports for financial reasons. In 2022, the University of Minnesota cut its men’s indoor and outdoor track and field, men’s gymnastics, and men’s tennis programs. In 2021, William & Mary cut its gymnastics, swimming, men’s track and field, and women’s volleyball programs. During the pandemic, the University of Iowa cut its men’s gymnastics, men’s and women’s swimming, and men’s tennis programs.

“In this era of media dollars going to fewer and fewer schools who carry a big brand name, and that’s not a large number of schools, schools like Arizona and others are asking the same questions,” Weaver said. “At what point is enough, enough?”

Weaver also pointed to what happened at Stanford University, which reversed course after announcing plans to cut nearly one-third of its varsity athletic teams. The university cited supporters of the program for helping to reveal new paths forward in funding the sports.

Despite Stanford’s success, Weaver said it’s rare to see that outcome.

“I’ve seen a lot of people talk about it and I’m curious on how that process worked at Stanford,” she said. “Often it requires a re-examination three years down the road: did everyone live up to the promises in the institutions?”

Weaver added that if programs are cut at the UA, she wouldn’t be surprised if there were protests and fundraising efforts. But creating an endowment to support a sports team for years to come can be nearly impossible.

“I have rarely seen it come to fruition,” she said.

Despite the financial hardships within the athletic department, the two highest paid employees at the UA are coaches. Men’s basketball head coach Tommy Lloyd makes $3.6 million per year and head football coach Jedd Fisch makes $2.1 million per year. Adia Barnes, the head coach of the women’s basketball program, falls within the top five earners at the UA, netting a yearly salary of $1.1 million.

And that doesn’t account for the number of assistant coaches and staff that some programs have. According to the UA athletic department’s staff directory, the football program has 50 employees.

“The marketplace that college football and basketball coaches have created for themselves, and the dependence on that revenue, is (extreme),” Weaver said. “Because everyone believes that you have to pay to get a coach that can keep you nationally competitive.”

The University of Arizona did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Facing a significant budget crisis, how much could UA save if it cut certain sports? Not as much as one might think. Other than the profitable men's basketball and football and football programs, all other UA men's sports lost $7.7 million combined in 2021-22.