University of Arizona instructor Brian LeRoy used to wonder why some students never bought the $240 textbook for his physics class

He suspected some couldn’t afford it, so he tossed the pricey tome.

Now he teaches the course with a free online textbook, a change that saved 312 students close to $75,000 last school year.

“It’s been really positive for everyone,” he said of the switch. “I believe it has a lot of potential.”

LeRoy is part of a quiet revolution underway in Tucson to increase availability of free or low-cost learning materials.

The city’s other main purveyor of higher education, Pima Community College, also has started offering a limited number of classes taught entirely with open source material.

And both institutions are ramping up efforts to make traditional textbooks obsolete in some of their most popular programs.

“I am confident we can provide more free textbooks and make an even bigger impact on student success,” UA libraries dean Karen Williams said recently of the school’s new partnership with OpenStax, a nonprofit provider of free, peer-reviewed texts now used at one in five U.S. colleges.

The use of free resources is growing nationwide as schools strive to increase enrollment and graduation rates in the wake of government funding cuts.

Here and elsewhere, the effort is being backed by some of the biggest names in higher education philanthropy, such as the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

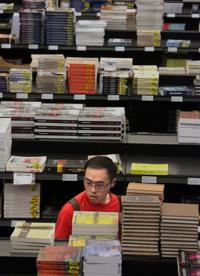

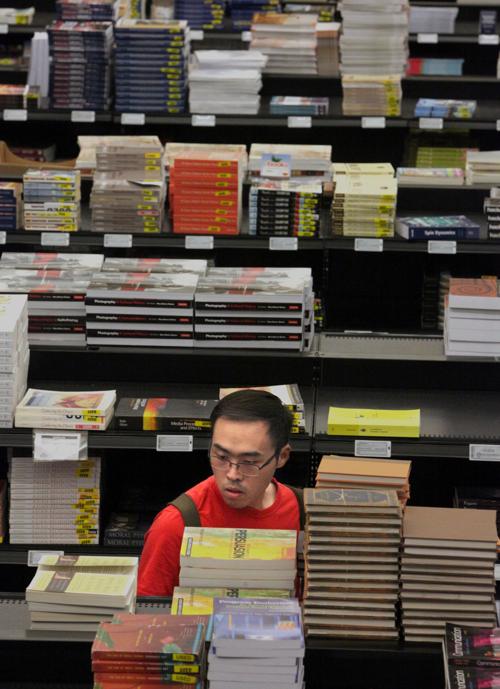

A typical college student now spends about $1,200 a year for textbooks, research shows. But the impact of those costs can vary enormously by institution.

At the UA, where full-time in-state tuition tops $10,000 a year, textbook costs typically add around 10 percent to the total cost of education.

At Pima, where in-state tuition is $1,177 a year, the price of textbooks more than doubles the cost of full-time attendance.

PCC spokeswoman Libby Howell said the school has already started making changes in response to student concerns about high textbook costs. For example, the college recently launched its first fully online degree program, an associate’s in Liberal Arts, that has no textbook costs from start to finish.

More changes are in the works after PCC recently won a $100,000 grant to create new online programs and increase the use of open-teaching resources. The funding came from Achieving the Dream, a national nonprofit devoted to student success.

Not every course has the potential for free textbooks. Much of the open material available today is concentrated in subject areas such as business administration, social sciences and computer science.

Faculty members have the last word on which teaching materials to use, so their buy-in will be a big deciding factor in how widespread free textbooks become.

Campus bookstores stand to be affected by the trend, so both local schools have invited bookstore representatives to be part of the discussions.

Richard Baraniuk, a Rice University professor who founded the OpenStax initiative that UA recently joined, said many free textbooks offer students the same quality as traditional texts.

“Open-source educational materials are building the same kind of legitimacy and audience that, until recently, has belonged solely to traditional publishers,” he said.

For LeRoy, the UA physics professor, the switch to free textbooks is a double win.

His students like saving money, he said, and he likes the fact that “now no one has an excuse for not doing their reading assignment.”