An instructional model that the Sunnyside Unified School District uses at two of its high schools has improved the schools’ academic performance, district officials say.

Sunnyside and Desert View High Schools have smaller schools within their schools called “freshman academies,” which separate ninth-graders from the upperclassmen, both physically and in terms of instruction to make the transition from middle to high school smoother.

Freshmen often lack the sort of academic behavior that is necessary to succeed in high school, said NJ Utter, the district’s college and career readiness director.

“We wanted to make sure that we were being very strategic about providing support for their transition year,” she said.

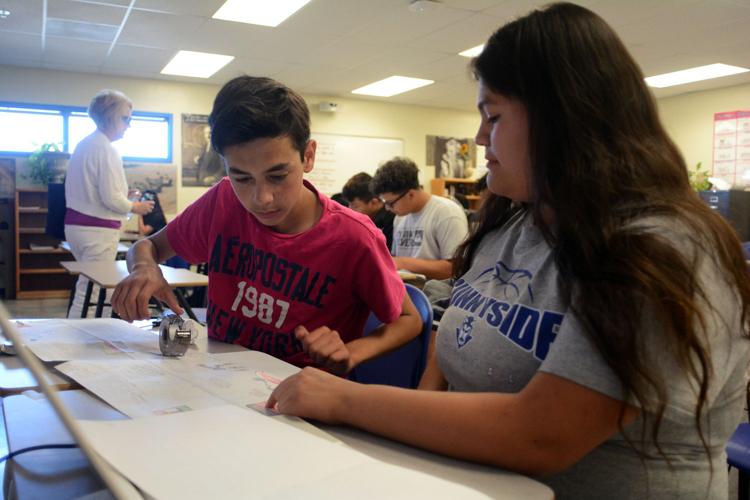

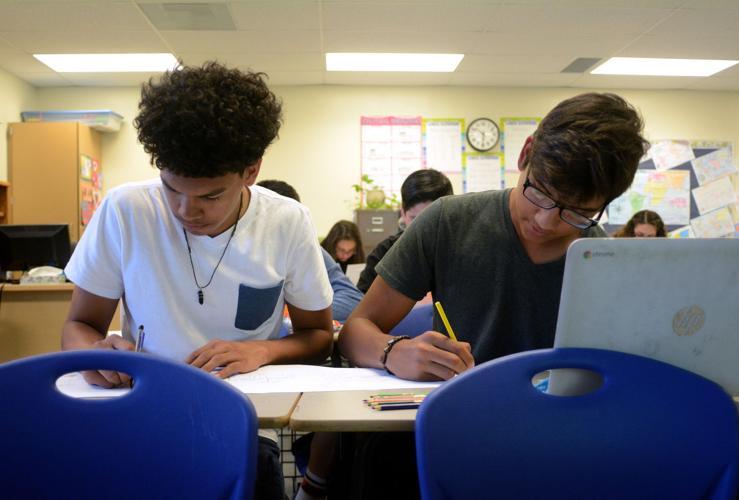

Each school dedicates a part of the campus, a principal, support staff, counselors and teachers to freshmen. Students and teachers of core subjects like math, science, English and world history, form smaller groups within the academy and work exclusively with one another.

The principals of both schools’ academies, which are in their fifth year of implementation, are reporting that test scores are going up, while failure rates are going down.

Data collected by the district showed that far fewer freshmen were failing in school. More than 700 Desert View freshmen failed in 2014, compared with 568 in the following year. Sunnyside High showed an even bigger improvement, with 224 fewer students failing.

Freshmen at those schools also did better on Arizona’s Instrument to Measure Standards, or AIMS, between 2011 and 2014, data about the formerly state-required graduation test showed. There was an increase of about 7 percent in math and 12.8 percent in reading scores.

Academic performance wasn’t the only area that showed improvement. Attendance also improved at both schools. Data showed that before the freshman academy model, Desert View’s attendance was just above 90 percent. That has increased to nearly 92 percent last year.

The district adopted the model in 2011 to improve attendance, dropout rates, academic achievement and provide greater support for freshmen’s transition into high school.

That support included dedicated resources and an extensive system of intervention that gives students multiple opportunities to make up their work, said Alissa Welch, Sunnyside High’s freshman academy principal.

There are several layers to the intervention system, which typically starts with a teacher reaching out to students who have not done their work or are struggling. If that does not yield positive results, a teacher may contact the student’s parents. The next step is to have a conference with the student’s core teachers, who work in teams and share the same group of students.

That should really send the message that work needs to get done, Welch said. But if that doesn’t work, then parents get involved in the meeting with teachers. The last resort is summer school enrollment. There are also support classes students can be placed in to help with algebra or literacy.

“It’s really hard for a kid to slip through the cracks here,” the principal said.

What makes that kind of system work is a level of collaboration that can only happen in a smaller learning environment, Welch added. There are about 650 freshmen total at Sunnyside High. Those students are split into groups of 150 and all share the same four core teachers, who themselves are a team and have classrooms adjacent to teach other.

Working in teams provides greater support not just for students, but teachers as well, said Kristin Luttrell, a freshman world history teacher. It makes collaboration easier.

“It works for everybody,” said the teacher, who has also taught sophomores before. She has three other people to depend on when a student is struggling.

Research supports the positive changes that Sunnyside district is experiencing with the freshman academy model. Christopher Fulco, head of Woodlyne School in Pennsylvania who, in his doctorate dissertation, researched the benefits of freshman academies, said he found that “students seemed to get through more subjects in the freshman year and fail less.”

Fulco was also a principal of a high school in suburban Philadelphia that had a freshman academy structure. Though his research did not confirm this, he also said he heard from many teachers that freshman students were behaving better.

Fourteen- and 15-year-olds are not as developmentally mature as 17- or 18-year-olds, he said. “They need a lot more direction,” he added.

The freshman academy model does not come without challenges and doubts. Success in freshman academies has not been proven to necessarily translate to success in the sophomore year, though there is also no evidence that students are dropping out then instead of in the first year of high school.

There has also been concern from teachers and others about the academy structure delaying the maturing process of the freshmen or that freshmen would advance to sophomores unprepared, Welch said.

But that’s largely a misconception, she said. In reality, the freshmen have a lot of opportunities to interact with upperclassmen, including in electives, extracurricular activities and pep assemblies. “They still get the experience of mingling.” As for the unpreparedness, the principal told the district’s Governing Board that teachers may see more unprepared students because students who would have otherwise dropped out are now sticking with school.

“We’re not saying we’re creating miracles and they’re coming to you these awesome, academic-achieving students, but you know what, they’re coming to you and that’s different than what used to happen,” she said.

Abrigail Martinez, 17, is part of the second cohort of seniors who have gone through the freshman academy system. She said going from the academy to the upper school took some getting used to, as she now had to travel farther for classes and got less attention from her teachers, but she was glad for the experience.

“It gave us that extra push.”