Counselor Heather McAuley hasn’t managed to sit down.

She hovers over her desk as she furiously clicks away on a student dashboard on the computer screen, half standing and half sitting, in her corner office at Desert View High School.

By 9 a.m. on a recent Friday, the veteran of 16 years has already made several trips to the attendance counter, principal’s office and copy machine. Three students, another counselor and a college and career readiness counselor have also visited with her.

“It’s an ever-revolving door,” she says.

On a typical day, McAuley sees anywhere from 20 to 25 students individually. Counselors at Desert View each have a caseload of approximately 300 students. In some Tucson schools the ratio is more than 500-to-1.

It’s hard to give each student enough attention, she says.

As Arizona school districts tighten their belts, they are having to ax more and more counselor jobs, leaving the state with the highest number of students per counselor in the country.

The American School Counselor Association recommends at least one counselor per 250 students. Arizona’s average is 941, compared with 491 nationally.

Our number is high, in part, because the state does not mandate counseling, counselors and experts say. In light of budget cuts, Arizona districts have reduced counseling positions in elementary and middle schools.

Calculating only for grades nine through 12, using data from the National Center for Education Statistics, Arizona’s ratio looks more like 435-1.

A Star analysis of Tucson-area public high schools’ counselor staffing data found that only one — Santa Rita, at 243-1 — meets the recommended national ratio. That school experienced a dramatic decline in enrollment in the past five years.

Other local schools with a ratio under 250 were mostly alternative schools with total enrollment of fewer than 250 students. For example, Tucson Unified School District’s Project More, which is an alternative high school for juniors and seniors, has one half-time counselor, making the ratio 168-1.

COMPARISONS TO ELSEWHERE

More than half of the states in this country require counselors, according to the counselor association. Far fewer have mandates on specific student-to-counselor ratios. Those mandates come from legislative action, administrative code or the states’ boards of education.

Vermont and New Hampshire, which rank No. 2 and No. 3 for lowest ratios, all mandate that schools have counselors. They also require a 300-to-1 ratio for higher grades. Their averages are 213 and 235, respectively. Only one other state, Wyoming, at 211, meets the national recommendation

However, having mandates does not necessarily translate to enforcement when a school is unable to meet the required ratio, said Amanda Fitzgerald, director of public policy for the American School Counselor Association.

Unless specific dollars are tied to counseling, such as special-needs students who must have individual education plans, schools or districts cannot be punished for not meeting the mandated ratio.

“I’ve never heard of that kind of thing happening,” she said. Fitzgerald said she couldn’t say for sure why those three states are able to achieve such low ratios, but added that smaller total student populations and higher spending on education could be factors.

Generally, reaching the association’s recommended ratio, which she said is based on years of research and tweaking as counselors’ responsibilities changed, would require all hands on deck.

“It takes an investment by the school system — by the school itself, by the school district and by the state to want to be able to provide those services,” she said.

“It really comes down to money,” Fitzgerald said. “When you look at all the education statistics, they are usually at the bottom in terms of funding.”

Arizona’s per-pupil spending was $4,016 in fiscal year 2013, compared with Wyoming’s $9,252, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s public education finance data.

Up until about three to four years ago, Arizona’s average counselor ratio was closer to the 500s, said Kay Schreiber, college and career readiness coordinator at the Arizona Department of Education. The state then saw steep cuts in education funding.

Less money meant some people had to go, she said. “School counseling just happened to be one of those areas that they started cutting.” Music, physical education and art positions were also eliminated.

When the choice is between keeping teachers or counselors, administrators and counselors say the obvious choice is teachers.

“I hate it,” McAuley of Desert View said. “But I’m also a teacher, so I get it.”

PERSONAL/SOCIAL, ACADEMIC AND CAREER

Back at Desert View, Carolyn, a junior, clutches a black coffee mug offered by her counselor. She is the fourth student to visit McAuley’s office on a recent Friday morning.

The teen has enough credits to graduate early and has been accepted to the University of Arizona. She was even offered a scholarship to attend college.

But there is a problem. Carolyn’s mother retired unexpectedly and cashed in her 401(k) for an emergency. That amount was reflected as income on the mother’s tax documents, which now makes Carolyn ineligible for the need-based scholarship.

Carolyn keeps calm for a while, but when it becomes clear that she will not be able to attend college this fall, she bursts into tears.

“Everything you worked for is screwed up, and that’s beyond your control,” McAuley tells her. “So let’s come up with a game plan.”

As a counselor, McAuley’s duties include looking after a student’s personal and social development, as well as academic and career or college planning, according to the counselor association’s national model.

At the high school level, counselors say they spend most of their time helping students plan their academic schedules, stay on track to graduate and manage attendance. Some of their other duties are designing, developing and implementing behavioral- and social-health programs, crisis response and giving lessons in classrooms.

The counseling association has for years encouraged schools to adopt more data-driven counseling programs, said Schreiber of the state Education Department. Data related to counseling includes anything from dropout rates and college application rates to federal aid application completion rates.

“You need to be able to draw the data and put into programs that would bring about student achievement,” Schreiber said.

Data could also help school counselors advocate for themselves, especially with superintendents, said Katherine Pastor, the counselor association’s 2016 School Counselor of the Year, who works at Flagstaff High.

TOO MUCH TO DO, TOO LITTLE TIME

Teresa Toro wears many hats. She’s primarily a senior counselor at Pueblo High Magnet School. But she’s also a sponsor of school clubs, department chair, event organizer, fundraising coordinator, community outreach specialist, test supervisor and mentor.

“If you want a monotonous job, this is not it,” she says. “Every day is a different day.”

Toro has a caseload of about 330 students because she is in charge of the seniors, who she says need a dedicated counselor because of graduation and post-secondary planning. Two other counselors split a caseload of about 1,200 students.

Toro also volunteers for the swim team, participates on the committee for the school’s recertification and helps during testing, which includes the state standardized test, PSAT, ACT and others.

Toro and several other counselors with whom the Star spoke all said not having enough time is one of their biggest challenges.

Her contract hours are from 7:50 a.m. to 3:20 p.m. But she says she usually leaves school around 5 or 5:30. And on some nights, she has school events to attend.

“You can’t get it all done within that time frame as a leader,” she says. “So you put in the extra time.”

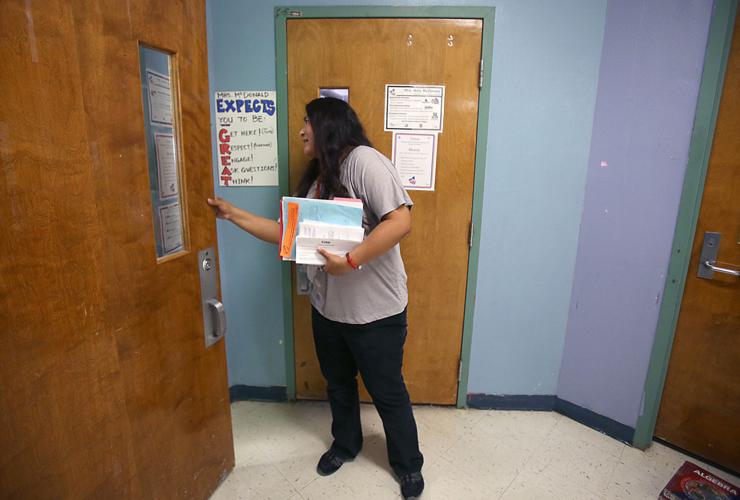

At Cholla High Magnet School, freshman counselor Alexandra Tsosie scrambles across campus between second and third periods on a recent Tuesday.

She plans to hit three classrooms for brief presentations on summer school. That’s just during the third period. She eventually needs to get the information out to 550 or so students. She’s already been to two classes this morning and her total goal for the day is 15.

Alexandra Tsosie, the freshman school counselor at Cholla High Magnet School, right, talks to algebra teacher Tanya Dewland about a student during the school day.

“I go into classrooms a lot,” she says. That way, she can reach more than one student at a time.

The Arizona State Board of Education requires educators to meet with every student in grades nine through 12 to plan for post-secondary options, whether it’s getting a job or going to college. The requirement doesn’t name counselors, but they frequently are the ones who do it. Meeting with groups counts, so counselors often interrupt class instruction to give presentations, such as the ones Tsosie delivers to rooms full of freshmen.

Between visiting classes and talking about summer school, Tsosie says she may need to duck out to help with test planning, which is considered a counseling duty at Cholla. Most other counselors interviewed for this story said they also help with test planning and proctoring.

Tsosie says she has always had a high caseload in the four years she has been at Cholla, so it’s difficult to imagine what she could accomplish with half the number of students.

“We could really tackle a lot of stuff if there was another person,” she says.

SHIFTING DUTIES

School counselors’ duties and responsibilities have shifted over the years, said NJ Utter, director of college readiness at the Sunnyside Unified School District.

As more and more support staff is eliminated, the people who are left, including counselors, are expected to pick up their work, she said. Counselors sometimes have to be on cafeteria or playground duty. A shortage of teachers means some counselors substitute in classrooms, she said.

With fewer people to go around, counseling has become less waiting for students to come see the counselor and more proactive behavior lessons and classroom visits, Utter said. “That’s not necessarily a bad thing.”

But increasing caseloads and broadly targeted counseling would inevitably mean quality could suffer, Schreiber of the state Education Department said.

“We’re not seeing the depth of counseling that we used to see,” she said.

Tsosie and other counselors said they would do anything to help their schools.

“Here, we’re ready to pitch in,” Tsosie said.

OUTLOOK

Most counselors and school administrators interviewed by the Star do not think the counseling association’s 250-1 ratio is realistic.

“Budgetarily, it’s not feasible,” Toro said. “But if the state of Arizona begins to fund education better, then that becomes more of a probability.”

Sunnyside’s Utter said because its maintenance-and- operations budget override election failed last November, the district has to cut one counselor from each of its two high schools.

Schreiber, of the state Department of Education, said what is more important than ratios is that schools are building comprehensive counseling programs.

Nevertheless, Schreiber believes Arizona’s student-to-counselor ratio will be on a downward trend in coming years.

“Districts are starting to see that counselors and what they bring to the schools are very, very important,” she said.

“We need our legislators and our government officials, our parents and our communities to realize that we really truly need professional counselors in every school.”

Federally, the American School Counselor Association is pushing to increase the amount of grant money that would be distributed to student support programs, some of which could fund counseling.

Congress has authorized $1.65 billion to be appropriated through Student Support and Academic Enrichment Grants to eligible school districts, though only $500 million has been confirmed to be appropriated thus far.

As it stands, Tucson-area high schools do not plan to increase the number of counselors.

But counselors say they love their work.

“You have to have the passion,” said Jessica Dale, a counselor at Amphitheater High. “If you’re just coming and going, then you can’t connect with the students.”

Toro of Pueblo Magnet said students who struggle and then make it to graduation keep her going.

“To see them through years of high school and transition to what’s going to be the next chapter of their lives, seeing the students bloom — that’s the payoff.”