Scientists have produced detailed maps of temperature changes in a lava field on Jupiter’s moon Io — made possible when weather, technology and the planets aligned.

Astronomers used the linked twin eyes of the Large Binocular Telescope on Mount Graham to measure the temperature of an overturning lava field the size of Lake Ontario on Io as its sister moon Europa passed in front of it.

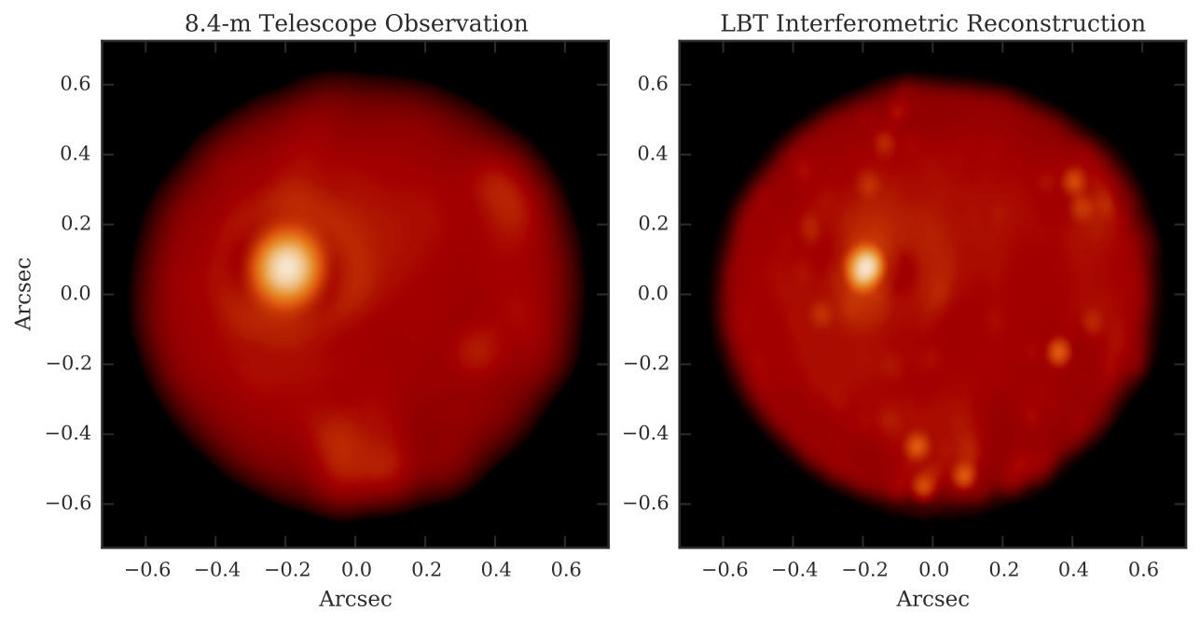

A combination of factors allowed the telescope to record images with a resolution equivalent to that of a 100-meter telescope, said Christian Veillet, LBT director and one of the co-authors of a research paper published Thursday in Nature.

In the paper, lead author Katherine de Kleer, a University of California-Berkeley graduate student, said the passage of Europa across the surface of Io allowed the team to record images and measure temperatures in 2-kilometer-wide slices as the moon’s shadow obscured and then revealed the surface of the volcanic crater called Loki Patera.

The LBT, meanwhile, was operating as an interferometer, combing the light from its two 8.4-meter mirrors into a single telescope with the resolving power of a telescope with a 22.8-meter mirror.

That provided the “unprecedented sensitivity” needed to determine how the molten lake periodically cools and warms, de Kleer wrote in the Nature paper.

The paper said the infrared observations of temperature variations showed the lake was “resurfacing” — cooling into a crust that then sank into, and was replaced by, the less dense lava.

Astronomers first noticed in the 1970s that Io brightens and dims periodically. NASA spacecraft then identified the source as volcanic eruptions, beginning with Voyager 1 and 2 in 1979.

These observations, made in 2015 in infrared wavelengths, were aided by the occultation, when one celestial body passes in front of another, hiding the other from view.

The contrast between red-hot Io and Europa’s icy surface made the images 10 times clearer than the resolving power — being able to distinctly distinguish two close objects — of the telescope itself, the paper said.

It was a serendipitous combination of clear skies above Mount Graham, a perfectly functioning telescope and camera, and the passage of Europa that provided the resolving power of a 100-meter telescope, said Veillet.

“This time, the resolution was given for free by nature,” he said.