Forget Planet 9 — that hypothetical giant in the distant realms of our solar system.

Two University of Arizona planetary dynamicists say we should be looking closer in for a body about the size of Mars that is responsible for warping the orbits of some smaller objects beyond Neptune.

Planet 10, anyone?

Kat Volk and Renu Malhotra expect their prediction to be verified when the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope begins mapping the entire night sky in the coming decade — sooner, if astronomers point their telescopes toward the galaxy center, where the planet-sized body may be hiding in a sea of stars.

“Closer in” is a relative term. We’re talking 4.6 trillion miles and beyond.

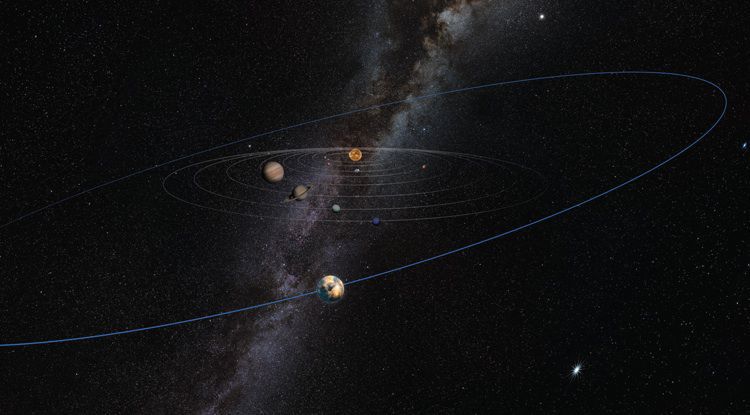

Volk and Malhotra base their prediction on a comparison of the orbits of 800 objects in and beyond the classical Kuiper Belt — where Pluto and hundreds of thousands of comets and icy rocks lie beyond the orbit of Neptune.

Most of the known Kuiper Belt objects, or KBOs, traverse the sky in long orbits on a plane roughly equivalent to the one on which Earth and all the other planets have settled.

But the study found 150 objects whose orbital plane is tilted from the average. They are farther out than the others — most between 50 and 80 astronomical units (AUs) from the sun. An AU is the average distance from Earth to the Sun.

“The vast majority of those objects are in what we call the classical Kuiper Belt, which is just a little bit outside Neptune’s orbit at 40 to 45 AU from the sun where Neptune is 30 AU,” said Volk.

Those objects orbit in roughly the same plane as Earth and the other planets.

“They are doing what we expect them to do and their average plane is the so-called invariable plane of the solar system, or close to it,” said Volk.

“But out beyond 50 AU, it looks like they are inclined about 7 or 8 degrees to what we expected it to be.”

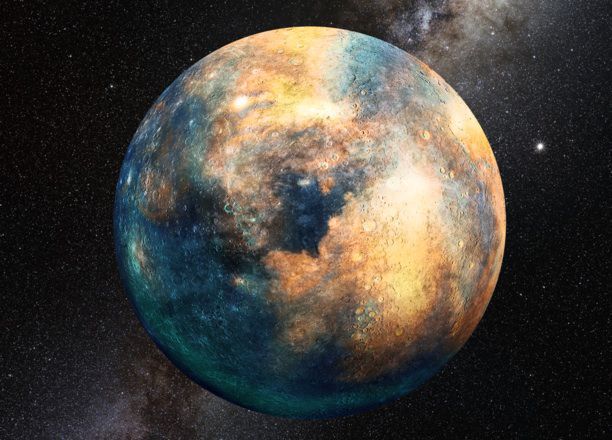

Something is warping their orbits, and the researchers calculate that it would need to be about the mass of Mars and in the same vicinity as the objects it is influencing.

Volk and Malhotra culled the most-complete orbits from years of observational data on 2,000 Kuiper Belt objects gathered by the Minor Planet Center.

Malhotra is a Regent’s Professor and the Louise Foucar Marshall Science Research Professor at the UA’s Lunar and Planetary Laboratory (LPL).

She has spent a lifetime studying what was once called “celestial mechanics” — the rules governing how bodies in space interact and eventually harmonize.

If there is a warp, there must be a cause, she said.

There are other possible explanations. The sample size could be a fluke, but they calculate only a 2 percent possibility of that. A wandering star may have induced the orbital change but that, too, is improbable.

If there is a Mars-sized planet not much farther out than Pluto, why have we not seen it?

Volk, a post-doctoral researcher at LPL, said the object “would certainly be visible to telescopes.” She said it must be somewhere we haven’t looked — possibly in the galactic plane where the light from billions of stars makes it difficult to differentiate faint objects closer by.

Surveys of the night sky avoid the area. “Solar system astronomers hate the galactic plane,” said Volk.

The object would have an orbital period of about 1,000 years, which means it would take 100 years to move through the galactic plane from the vantage point of Earth astronomers.

“For 100 years, it could just be sitting there and we wouldn’t know it,” she said.

Similar observations and calculations caused solar system astronomers to propose in 2014 the presence of what they called “Planet 9” — a giant body 10 times the mass of Earth, that influences the orbits of six large objects.

Planet 9 would be 10 times farther from Earth than the smaller planet proposed by Volk and Malhotra — too far away to influence the orbital warp they discovered.

We tend to think of the solar system as this tiny corner of a mid-sized galaxy in a vast universe, but it, too, is vast and much about it remains unknown. Malhotra compares our understanding of the Kuiper Belt to our knowledge of the asteroid belt between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter in the early 1900s.

It won’t take 100 years to close that knowledge gap, but it won’t be done in the next decade, Malhotra said.

The Large Synoptic Survey Telescope, the next-generation, sky-mapping machine developed in Tucson and being erected in Chile, will provide “an order of magnitude jump to that knowledge,” said Volk.

Volk and Malhotra call their proposed discovery a “planetary-mass object” to avoid the planet-definition controversy that demoted Pluto to dwarf and to satisfy a referee for The Astronomical Journal, where their paper has been accepted for publication.

So they also don’t call it Planet 10, but that name has proven irresistible to others.