An asteroid caught in the orbit of Jupiter is bucking the tide, traveling in a direction opposite to the million or so objects that orbit our sun.

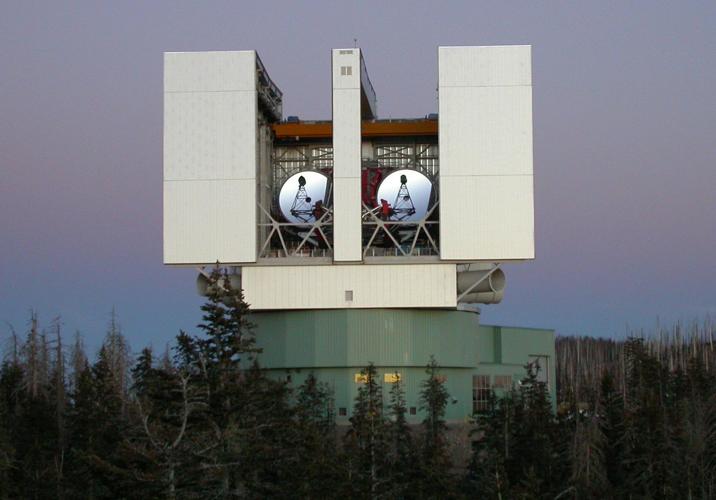

Christian Veillet, director of the Large Binocular Telescope on Mount Graham in the Pinaleno Mountains near Safford, and colleagues reported Wednesday in the journal Nature that the tiny, unnamed object has survived in its seemingly perilous orbit for a million years.

“I compare it to a new species found somewhere in the bottom of the ocean or some weird place on Earth,” Veillet said. “It is an interesting animal.”

The object, about three kilometers in diameter, uses the gravitational nudge of giant Jupiter to alternately pass safely inside and outside of the planet’s orbital plane every six years, never coming closer than 109 million miles.

Of the 726,261 known asteroids, only 82 orbit in a clockwise, or retrograde motion, Veillet, and Canadian colleagues Paul Wiegert of Western University in London, Ontario, and Martin Connors of Athabasca University in Alberta, reported in Nature.

What makes this asteroid unique, according to the most recent research, is that it is the only one known to co-orbit with a planet in the opposite direction.

The object, known provisionally as BZ509, was discovered in 2015 by the University of Hawaii’s asteroid-hunting Pan-STARRS telescope.

“At the time, its orbit was not sufficiently well-known to determine its behavior,” according to the paper. “But it appeared to be suspiciously close to Jupiter’s co-orbital zone, so the authors of this paper tracked it down and obtained further observational data using the Large Binocular Telescope Observatory in Arizona.”

Weigert, Connors and Veillet used archived data and additional observations to plot the arc of the object over 300 days — long enough to provide a reliable simulation to determine that it does share Jupiter’s orbital space.

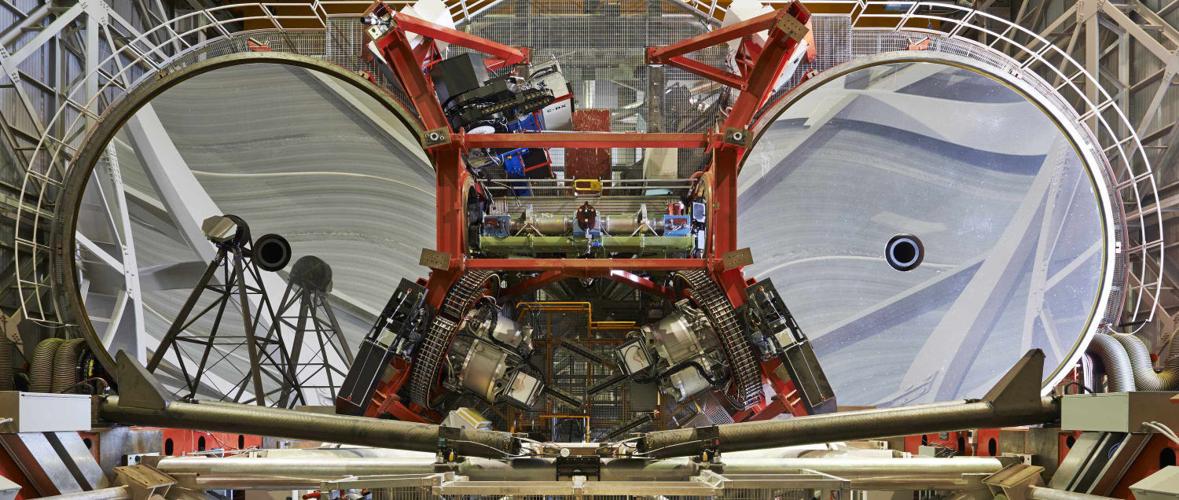

Final confirmation of its retrograde orbit was made with 16 observations by Veillet at the LBT, whose twin 8.4-meter mirrors represent a bit of overkill for solar system observations.

The LBT, an international collaboration led by the University of Arizona, can operate as the largest telescope on Earth when light from its two mirrors is combined.

“It was just a bit too faint for the smaller telescopes dedicated to our solar system, but for LBT, it’s an easy target, which is nice because we didn’t spend much time using the telescope,” Veillet said.

“Even though we try to use it for things no one else can do, it also does these kinds of basic observations which produce interesting science,” he said.

Veillet said he, Weigert and Connors first began collaborating on interesting objects in the solar system when he was director of the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope.

In 2011, the team confirmed the co-orbital status of the first, and only, known Earth “Trojan.” Trojans are asteroids that co-orbit with planets at stable points where the gravitational pull of the planet and the sun cancel each other.

The collaboration has continued in a long-distance arrangement, he said. “We regularly look at the weird objects in the solar system.”

This asteroid could be a comet, according to the Nature article. It hasn’t brightened during the observations, which would indicate a tail of vaporizing ice, but it hasn’t been observed in a close approach to the sun.

Comets, like the famed Halley’s comet, are more likely than asteroids to have retrograde orbits.