Seven recently discovered planets that are closely orbiting a dim star dubbed Trappist-1 are the best places to look for signs of life outside Earth, NASA and European scientists said Wednesday.

There are better places to look for truly Earth-like planets that orbit their stars at greater distances, said a University of Arizona exoplanet investigator, but solar systems like our own have eluded discovery.

“This is exciting,” said Daniel Apai, who heads a NASA astrobiology research program tasked with finding the best places and techniques for finding signs of life elsewhere in the universe. Apai said his entire group at the Earths in Other Solar Systems program gathered around the television Wednesday to watch the NASA announcement of the discoveries.

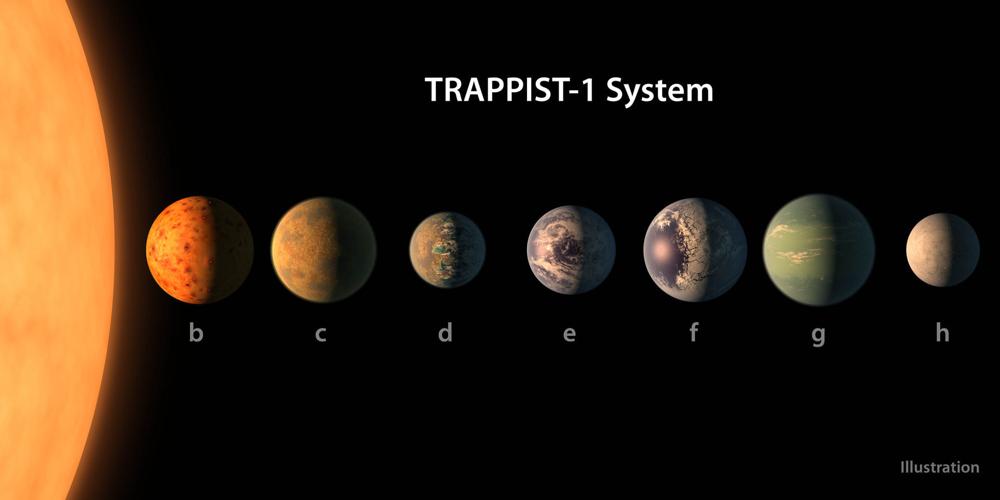

NASA scientists and the Belgian astronomer who led the study of planets orbiting Trappist-1 described the discovery as a “compact solar system” — a miniature analogue to our own, with Earth-sized, presumably rocky, planets orbiting close to a cooled-down star.

Michael Gillon, astronomer at the University of Liege in Belgium, revealed the discovery of three planets in a solar system around Trappist-1 in May 2016. They were found by Gillon’s Transiting Planets and Planetesimals Small Telescope — TRAPPIST — in Chile.

The star takes its name from that telescope. The planets themselves are simply labeled Trappist b through h. “We have plenty of possibilities that are all related to Belgian beers,” Gillon said when asked at the televised announcement and press conference if he had names for his discoveries.

Gillon’s discovery of the three planets led to a massive imaging campaign using some of the biggest telescopes on Earth and days of precious time on NASA’s space telescopes, including 500 hours on the Spitzer Space Telescope.

Gillon and colleagues identified seven planets, with three of them orbiting at a distance that places them in the habitable or “Goldilocks” zone, where temperatures would be conducive to the presence of liquid water.

“In this planetary system, Goldilocks has many sisters,” said exoplanet authority Sara Seager.

“We just made a giant, accelerated leap forward in the search for habitable worlds,” said Seager, professor of planetary science and physics at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge.

Gillon said he had been intrigued since childhood “about the possibility of the existence of life elsewhere.”

“We are getting nearly there with this result,” he said.

The star in question is part of a class of dim stars known as M dwarfs. It is less than one-tenth the size of our sun and considerably cooler.

That means planets can orbit closely and still be in the habitable or “Goldilocks” zone, where it’s neither so hot that water vaporizes nor so cold that it is perpetually frozen.

Three of the seven planets lie within that region — theoretically. They are all believed to be rocky based on their size, and some may contain water.

For now, astronomers know only their sizes, their masses and their orbital periods, which range from 1½ to 12 days for six of the planets. The orbital period of the seventh is unknown. The discoveries were published Wednesday in the scientific journal Nature.

“From past studies, we predicted there would be more Earth-like planets around M dwarfs but that was a statistical prediction,” said Apai.

“This is really unlike anything we have seen,” said Apai, who was not part of the study.

Apai said the closeness of the planets to their sun and the assumption that they are tidally locked — rotating once during their orbit so only one side ever faces the sun — could mean a much different chemistry and atmosphere.

“That is the next question: Whether they are Earth-like or just Earth-sized.”

Steward Observatory astronomer Katie Morzinski, who returned Wednesday from an observing run in Chile where she and her Magellan AO colleagues are attempting to directly image exoplanets, said little is known about what could happen over time to a planet that is tidally locked and so close to its sun.

“So in that sense the seven planets orbiting a late M dwarf star are a pretty uncertain area to look.” But Morzinski noted in an email that no area is “certain” when it comes to planet-hunting.

Morzinski said Trappist-1 is close enough to observe (39 light years away) and presents better odds for finding habitability with three or four planets potentially in the habitable zone.

Apai said planets are easier to find around smaller M dwarfs, using a method that measures the reduction in light caused by their passage in front of the star during orbit. The smaller the star, the bigger the signal, he said.

They are also easier to study, and astronomers will now use telescopes in space and on Earth to characterize the planets’ atmospheres by looking for the spectral signature of elements.

Success in that search may have to wait for the 2018 launch of NASA’s next-generation James Webb Space Telescope, which will have the capability to determine if the planets have elements and compounds that would signal the presence of life, said Nikole Lewis, astronomer at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore.