The longtime operator of El Tour de Tucson is in deep financial trouble, awash in red ink and unable to repay a six-figure debt owed to Pima County taxpayers, public records show.

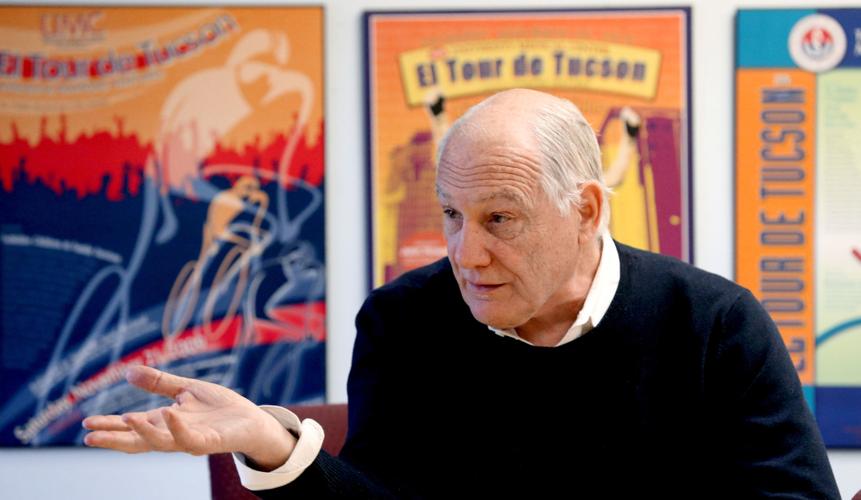

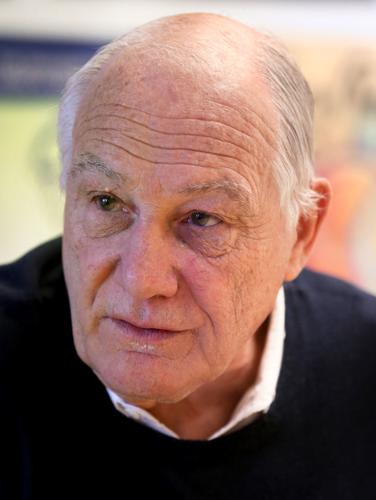

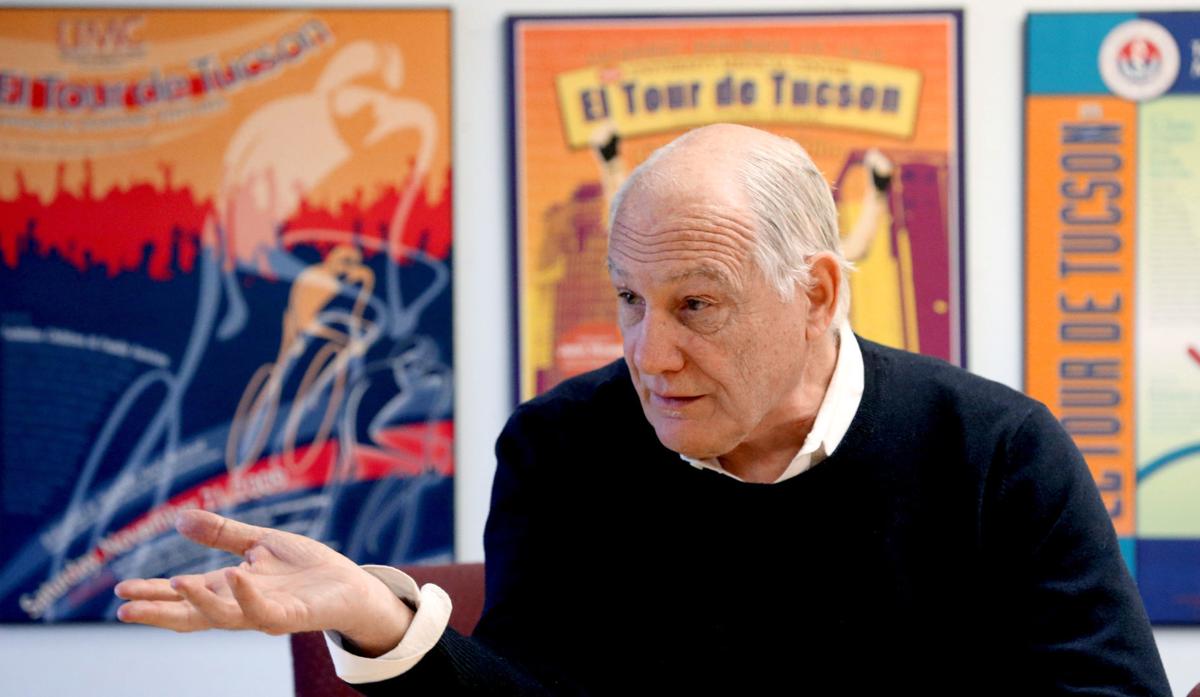

The future of the premier cycling event is up in the air, and its founder, Richard DeBernardis, is stepping down to make way for new leadership as the county threatens to sue over a $180,000 bill that has gone unpaid since last year’s race in November.

The overdue tab is for barricades and traffic signs the county agreed to procure in bulk to help El Tour cut costs, on condition the funds be reimbursed in full before the end of 2018.

County Administrator Chuck Huckelberry says the county, which also provides El Tour with $30,000 a year in grant funding, could cut off future support if payment is not forthcoming.

“Until this bill is paid, there is no need to discuss any future El Tour de Tucson event,” Huckelberry said in a recent internal memo.

The memo was followed by a Feb. 12 warning letter from the Pima County Attorney’s Office. It gives El Tour’s nonprofit operator, the Tucson-based Perimeter Bicycling Association of America, 90 days to pay to avoid legal action.

In an interview, Huckelberry said Perimeter CEO DeBernardis, who founded El Tour 36 years ago and has run it ever since, needs to go.

DeBernardis, 74, deserves great credit for creating the event and keeping it going for decades, he said, but given the current situation, “at this point it probably needs professional management.”

Huckelberry expressed concern over how Perimeter plans to repay the county — by diverting advance registration fees paid by cyclists in the upcoming El Tour de Mesa, a smaller race he runs in that city every April.

It’s unclear how that might affect the Mesa event, which typically breaks even.

DeBernardis confirmed the diversion plan in an interview last week with the Arizona Daily Star. While legal, such an arrangement is indicative of “poor financial management,” Tempe attorney Ellis Carter, a nonprofit expert, told the Star.

In the interview, DeBernardis said he’s done his best but has grown weary and doesn’t feel capable of addressing El Tour’s increasingly complex challenges. He plans to leave permanently by year’s end.

“I don’t know how to manage a multimillion-dollar operation,” he said.

“If I stay, El Tour will die.”

RED INK

Whoever takes over will have to work quickly to stanch the flow of red ink.

Perimeter’s nonprofit tax returns show financial losses in three of the last four years. It lost $170,000 in 2015 and $216,000 in 2016, and 2018 losses could be up to $150,000, DeBernardis said.

The situation has set off alarm bells for publicly funded entities that give annual grants to support El Tour. Last year’s grants totaled at least $65,000 from the county, the city of Tucson and Rio Nuevo, the downtown redevelopment district funded with tax dollars.

“I think everyone in this community became concerned when El Tour couldn’t pay their bills,” said Fletcher McCusker, the board chair of Rio Nuevo, which gave El Tour a $25,000 grant in 2018.

DeBernardis has often claimed — without evidence — that Tucson receives a financial boost of “between $18 million and $30 million” on El Tour day alone. In fact, the economic impact is unknown because an in-depth study has never been done.

Last spring, the town of Oro Valley turned down DeBernardis’ request for a $15,000 contribution, and gave $5,000 instead because Perimeter couldn’t show how the expense would benefit the town.

“Before agreeing to cover costs, the town requested recent economic impact data, which the El Tour race director could not provide, so the town did not commit to covering those expenses and the race was re-routed,” said a statement from Oro Valley’s public affairs office.

McCusker said Rio Nuevo plans to fund a detailed economic assessment of El Tour this year to allow for an accurate cost-benefit analysis.

Tucson lawyer Pat Lopez, a cycling enthusiast and longtime Perimeter board member, said the organization has been cutting costs and has tried for years to boost ridership, for example, by adding noncompetitive events such as the family-friendly El Tour Fun Ride.

But the changes have had limited effect, and DeBernardis and the board have mutually agreed the nonprofit needs new leadership to turn things around. The change has been under consideration for some time, Lopez said.

On Wednesday, the board changed DeBernardis’ title from CEO and board chair — positions he held concurrently, an anomaly in the nonprofit world — to CEO emeritus. The board voted to have him stay on in an advisory role this year at his full $108,000 salary.

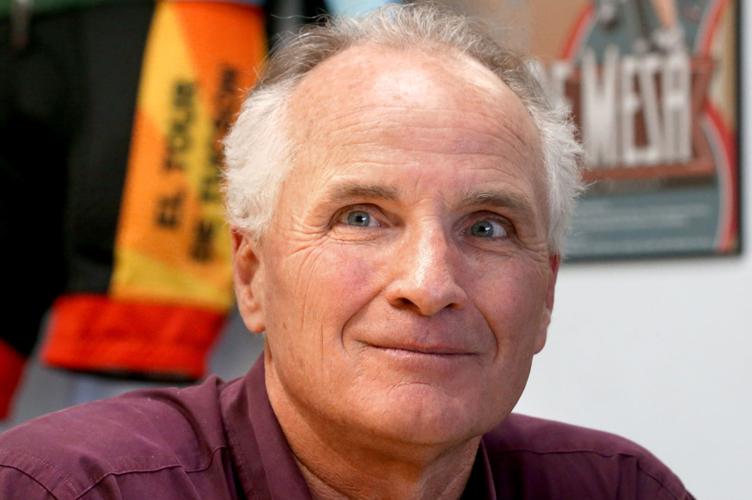

For now, Perimeter will be run by a volunteer interim CEO with extensive experience in competitive cycling but no background in nonprofit management.

The interim leader, retired educator Doug Holland, 58, said he plans to spend 10 to 15 hours a week seeking new funding and overseeing a search for a permanent CEO.

Lopez said the board will meet Monday, March 4, to discuss other potential corrective measures, such as staffing adjustments and hiring a professional, outside management firm to run this year’s El Tour.

One of the potential staffing issues may affect DeBernardis’ sister, Beverly Blohme, 81, who is listed in tax records as Perimeter’s treasurer/secretary and draws a $55,000 annual salary.

“We will be talking about some financial issues and we expect to be making some changes, but it is not intended to reflect on Beverly or our trust and confidence in her,” Lopez said.

SHRINKING RIDERSHIP

DeBernardis staged the first El Tour de Tucson in 1983 with 198 participants and has watched it grow to include several thousand riders a year from as far away as Australia and Japan.

In its heyday, the event drew cycling celebrities such as Lance Armstrong and Greg LeMond to Tucson. And it has raised several million dollars a year for area charities by having participating cyclists hit up their friends, relatives or employers for donations.

But El Tour’s traditional ridership has fallen by more than 30 percent over the last 10 years, with a concurrent drop in revenue from rider registration fees, the Star found in an analysis of annual event results from 2008 and 2018.

DeBernardis can’t say for sure what’s behind the decline, which he says is happening at similar events nationwide. But he has some theories.

Cycling used to have heroes like Armstrong who generated excitement and inspired others to participate. But its wholesome image was tarnished and has not recovered from doping scandals involving the former cycling star, he said.

He also suspects the 2016 presidential election siphoned away funds from El Tour when people chose to spend their money instead on donations to political candidates.

Weather, too, may have played a role. A huge rainstorm during the 2013 El Tour was followed by a trend of lower ridership over the following years, and “we have never really recovered,” he said.

SPONSORSHIP FATIGUE

Another big factor affecting the bottom line is El Tour’s recent inability to secure large corporate sponsorships, which used to bring in $200,000 to $300,000 a year.

Many previous six-figure sponsors — local hospitals and casinos for example — are unwilling or unable to continue giving and Perimeter did not keep up with a trend toward smaller sponsorships from a larger variety of sources.

“The charitable giving environment has changed dramatically away from big donors, but El Tour never really made that conversion so they’re still relying on very large sponsors even though those days are over,” said McCusker, of Rio Nuevo.

“I don’t think anyone is going to put up a quarter-million dollars to sponsor a sporting event. There’s just not that kind of interest anymore.”

To survive, El Tour will need to make substantial changes, such as increasing rider fees, expanding its support base to include smaller donors, and reworking cycling routes to reduce the need for costly traffic control equipment, McCusker said.

Lopez said Perimeter’s board is prepared to do what it takes to revive El Tour.

“I truly believe this event is a tremendous benefit to the community,” he said.

“This is not your typical nonprofit. It’s a labor of love.”