The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service pulled several tough mitigation measures for the proposed Rosemont Mine this year after the Forest Service objected to them, federal records show.

Backfilling the open pit, kicking cattle off riparian areas and protecting against invasive, non-native species for 150 years were listed in an early draft of a federal biological opinion for the mine. The measures, which would have been mandatory, were excised from the wildlife service’s final opinion for the mine, published in April 2016.

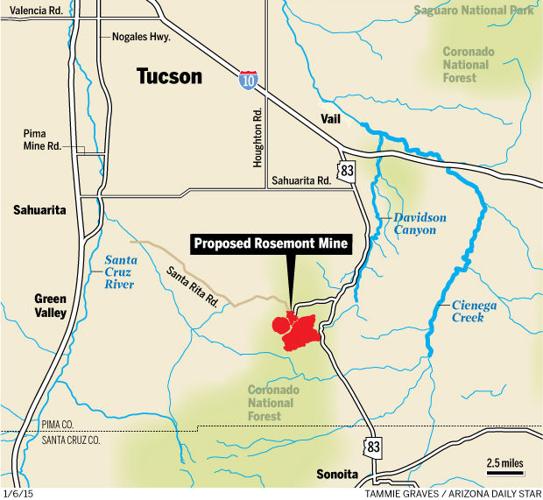

The mine would extract copper and dispose its waste on private and federal lands in the Santa Rita Mountains 30 miles southeast of Tucson. As part of the approval process for the mine, the Fish and Wildlife Service requires measures to lessen or compensate for the mine’s impacts.

Hudbay Minerals Inc., the Toronto-based company proposing to build the Rosemont Mine, objected to these measures along with the Forest Service.

The Star obtained details of the early measures and the Forest Service’s objections through the federal of Freedom of Information Act.

Another since-pulled measure in the November 2015 draft, which was never publicly released, would have required Rosemont to ensure that the San Rafael Valley and Upper Santa Cruz River watersheds — an area critical to the survival and recovery of an endangered fish called the Gila chub — “be secured and maintained as a wholly or nearly wholly native community over the next 150 years.” Similar measures were planned for the threatened Chiricahua leopard frog and the endangered Gila topminnow and desert pupfish.

In all, the measures were targeted to protect seven of the 12 imperiled species known to live on or near the mine site. The other species were the endangered Huachuca water umbel, a plant, and the threatened Northern Mexican gartersnake and Western yellow billed cuckoo.

For the final biological opinion, the two agencies and the mining company agreed on three other conservation measures — less expensive, less sweeping and less controversial:

- A $3 million invasive species control program would control non-native catfish, bullfrogs, sunfish and crayfish and non-native plants in the Cienega Creek and San Rafael Valley-Santa Cruz River watersheds. It isn’t required to be effective for 150 years.

- A full-time staff biologist would monitor the effectiveness of mitigation and conservation measures, including 4,800 acres of land purchases Rosemont has agreed to make outside the mine area.

- A $1.25 million program would replace riparian habitat damaged by the mine and improve other habitat to benefit the endangered Southwestern willow flycatcher and the yellow-billed cuckoo.

The biological opinion must be finished before the Forest Service and the Army Corps of Engineers make final decisions on whether the mine can be built. The agencies have said they’ll make their decisions this summer, with the Corps’ decision possible within weeks.

Huckelberry: Backfill

mandate reasonable

Opponents of the mine, who want it operated under the strictest controls possible, said the wildlife service gave up too much protection from environmental damage caused by the $1.5 billion project. If approved, it will mine 243 million pounds of copper annually.

“Many of those measures seemed very reasonable to me, considering the potential long-term, direct, indirect and cumulative impacts of the proposed mine,” said Christina McVie, the Tucson Audubon Society’s conservation chair. “We’re in the middle of a 17-year, state-declared drought emergency. The fact that we would sacrifice any naturally occurring seeps, springs and riparian flows without adequately mitigating for those is in my mind unconscionable.”

The most significant deletion was removal of the backfilling measure, said Pima County Administrator Chuck Huckelberry. It appears to have been ruled out without conducting a cost-benefit analysis that the county suggested long ago, he said.

Imposing mitigation measures lasting 150 years is “perfectly appropriate,” he said. There’s well-documented evidence that pollution from hard rock mining often occurs after the mining is finished, he said.

The Forest Service said it lacked authority to carry out some of the proposals, particularly those involving private land and whose management would last 150 years. Backfilling in particular also has been found economically unfeasible, the service said. Other grazing measures should be tried before full-scale removal of cattle from riparian areas, the service said.

Coronado National Forest Supervisor Kerwin Dewberry said backfilling was already addressed in the mine’s 2013 final environmental report , including an economic analysis.

“We followed the process and we disclosed the information we needed to disclose based on the National Environmental Policy Act,” said Dewberry. The law requires publication of an environmental impact statement for major projects such as Rosemont.

Wildlife service official Steve Spangle said the Endangered Species Act limits what the agency can ask for or impose in the biological opinion. Even though these tough measures didn’t survive, the service had already come up with a significant amount of mitigation even before it started on the biological opinion, and the Forest Service came up with more ideas after the November 2015 draft appeared, she said.

“If the Forest Service said it’s not in their authority, we feel we can’t order them to do it,” said Spangle, the wildlife service’s Arizona field supervisor.

The wildlife service also can’t, under its rules, adopt any measure that’s considered more than a minor change to the project, unless it’s shown to jeopardize endangered species, which wasn’t the case for Rosemont, he said.

In its comments on the draft opinion, Hudbay staff used phrases such as “red flags” and “Christmas wish list” of measures to sum up its view that the measures were far out of scale to what it felt will be the mine’s true impacts.

The company said the measures were poorly written, open-ended and too easily open to interpretation.

“We were flabbergasted by the contents of the document,” Brian Lindenlaub, a biologist for Rosemont consultant Westland Resources, wrote in a Dec. 4 email to the Forest Service.

The mining project would create about 400 long-term jobs and spark creation of another 1,600 jobs in the surrounding community, a Rosemont-funded economic analysis by an Arizona State University economist found. But mine construction would blade 5,431 acres of federal and private land, and impact up to 146,000 acres, the final Rosemont biological opinion said.

The federal agencies, the mining company, environmentalists and supporters of the mine disagree — sometimes heatedly — over whether the project would dry up nearby riparian areas or contaminate the Cienega Creek watershed that feeds the urban Tucson aquifer.

Evaporating ‘pit lake’ will follow closure

Backfilling was the most sweeping measure in the wildlife service’s draft opinion. It would require Rosemont to scoop up waste rock and mine tailings it leaves behind from processing copper ore, and return it to the half-mile deep open pit after it stops mining copper in 25 years or so.

The process, intended to reduce water loss from evaporation in the open pit after mining stops, is required for all new open pit mines in California, but none has reached the point of needing to backfill yet.

dangers outlined

for bulldozer drivers

To create an open pit, Rosemont would have to pump groundwater. That would reduce how much flows to neighboring streams such as Cienega Creek and Davidson Canyon.

After the mine closes, the open pit would become a “pit lake” whose surface water would evaporate, which critics fear would put continued pressure on the aquifer and Cienega Creek.

Other ideas in the draft opinion included an underground grout “curtain,” a wall, impermeable to water, that would prevent the drawdown of the aquifer caused by creating the open pit from affecting the creek.

Or, the mining company could put large plastic shade balls in the lake to block the sun’s evaporative force.

“The state of reclamation is still in the 20th century — we dig open pits and we put all the overburden as well as tailings in a massive landfill,” Huckelberry said in explaining why he favors backfilling. “The process of reclamation is such that, historically, you basically clean up where you find pollution.

“One would think that, in the 21st century, we ought to take a different approach to reclamation, where we minimize the footprint,” he said.

But backfilling all of Rosemont’s waste rock into the pit would cost an estimated $654 million to $996 million. It would take 16 years, 24 hours a day, to handle about 881 million tons of material, the Forest Service said in its 2013 final Rosemont environmental impact statement.

Either dumping all the waste rock directly into the pit or hauling it by truck would present major safety concerns, the Forest Service said. For example, hauling wastes downhill in large trucks is dangerous in open pits, especially those with sharp switchbacks. There’s not enough room for safety pullouts or escape ramps, or to redesign the switchbacks, the service said.

Dumping the waste over the pit rim also poses problems, the Forest Service said.

“Dumped material would likely be pushed downward by bulldozer operators, who would be exposed to potential risks such as overturning equipment, rock avalanches, and burial by unstable material,” the service said.

In 2011, however, Huckelberry wrote in a memo that even if you pegged the total backfill cost at $1.5 billion, the mine would still earn $603 million in profits over 21 years at a $1.85 a pound copper price and more than $12 billion at a $4.59 price.

He said recently that a study should compare costs versus economic benefits of keeping workers employed longer at the mine and the environmental benefits of reducing the open pit’s pressure on the aquifer. Rosemont officials have said Huckelberry’s 2011 estimates of the mine’s expected profits were highly exaggerated.

Backfilling was left in the final biological opinion — but only as a voluntary measure.

It recommends that the Forest Service and Army Corps make sure Rosemont researches ways to reduce groundwater use and loss, “considering any and all current and future techniques that may be technologically and economically feasible.”