Second of four stories

|

A 911 call from a migrant in distress in July 2020 sent Border Patrol agents into the desert on the Tohono O'odham Nation reservation. They found the caller near Arizona 86. But that day's search was not over.

Another man needed help to the south, the caller said.

Agents relayed the information to an Air National Guard helicopter pilot, who spotted Jose Antonio Guillermo, a Mexican citizen, lying face down under a palo verde tree about half a mile away. The pilot guided Border Patrol paramedics to Guillermo, but when they found him he was gasping for air, a tribal police report says.

An agent poured ice water onto Guillermo's face to try to cool him down and then ran to his truck to get a heart monitor. Guillermo's heart rate was dissipating and he no longer had a pulse. Two more Border Patrol paramedics arrived and over the next 25 minutes they performed CPR, consulted a doctor, and injected him with epinephrine and atropine.

Despite their best efforts, they had arrived too late. Guillermo died, just a week after he turned 23.

Calls for help come from migrants stranded in mountain ranges, such as the Baboquivari Mountains southwest of Tucson where trails rise up steep mountainsides and crisscross ridges. Migrants call when they are lost in the desert dozens of miles from the nearest signs of civilization. Calls also come from family members desperate to know what happened to loved ones who went missing after crossing the border.

Those calls spur Border Patrol agents, paramedics and sheriff's deputies to hustle down remote roads or fly helicopters along mountainsides. The calls prompt humanitarian aid volunteers from groups like Tucson-based No More Deaths to coordinate between family members and first responders.

Rescuing migrants in the desert requires overcoming a multitude of challenges, the Arizona Daily Star found by analyzing incident reports from sheriff's departments and other local law enforcement agencies, audio recordings of 911 calls, and data from medical examiners in Pima and Yuma counties.

Some calls came before medical help was needed, but others came just minutes before the caller or their companions succumbed to heat and dehydration.

"I need help. My friend is dying. Hurry! Hurry!" one man said in a call from the Altar Valley north of Sasabe. "He's not drinking water anymore."

"Please, help. I'm alone. They left me," a man said through tears in a call from east of Arivaca.

"My chest hurts, my heart," the man said when the 911 dispatcher asked him if he was injured.

"We're lost in the desert. Can you help us? I can't take it anymore," a man said in a call from the Three Points area.

"I don't have anything left to eat. I don't have any water. I feel like I'm going to pass out," a woman said in a call that pinged off a cellphone tower near Green Valley.

Some areas have spotty reception, leading to frequent dropped calls as 911 dispatchers and Border Patrol agents try to gather information from the migrant in distress. In other, huge areas of the desert west of Tucson, there is no cellphone coverage, making calls for help impossible.

The wilderness in Southern Arizona is as large as several states, and would-be rescuers often have little information about where distress calls come from. When they have an exact location, they may still have to travel long distances over rough terrain to make the rescue.

Rescue efforts unfold across 20 jurisdictions that include local sheriff's departments, U.S. Fish and Wildlife officers, National Park Service rangers, and the Tohono O'odham Nation Police Department. When calls come from areas that could be in multiple jurisdictions, 911 dispatchers have to figure out where to refer the call.

The de facto situation is that the Border Patrol has dual roles as the main enforcer of immigration laws and the main responder to migrants in distress. At the same time, search-and-rescue efforts technically are the responsibility of county officials, not the Border Patrol.

Either way, local law enforcement agencies and the Border Patrol have limited resources to respond to these distress calls.

Humanitarian aid volunteers see saving migrants as their top priority, but they do not have the authority to take effective action. Their efforts are hemmed in by federal agencies like the Border Patrol and the U.S. Attorney's Office.

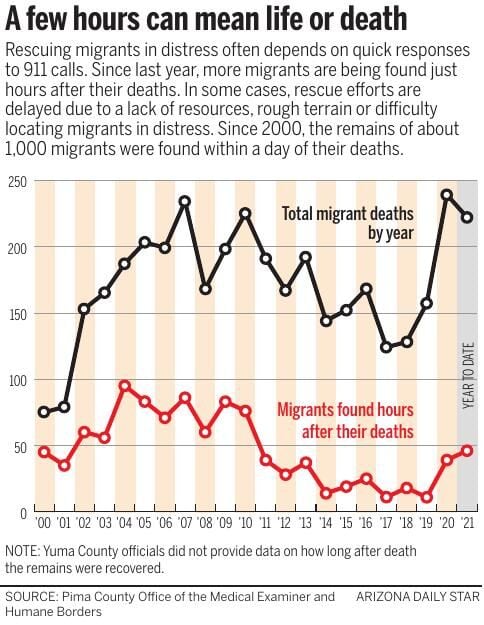

The speed and effectiveness of rescues have become even more important over the last two years as more migrants were found shortly after their deaths.

Just in June, the bodies of 16 migrants were found within 24 hours of their deaths, the highest monthly total in at least a decade and more than all such cases reported in 2019. Another 13 sets of remains were found within one week, also the highest monthly total in at least a decade, according to Pima County's medical examiner. More than 1,000 sets of remains have been found within one day of death since 2000.

Rescues are not keeping pace.

The Border Patrol's Tucson Sector reported rescuing 14 migrants in need of medical care from May to July. During those months, the remains of 126 migrants were found, including 35 who were found within a day of death and 25 within a week of death.

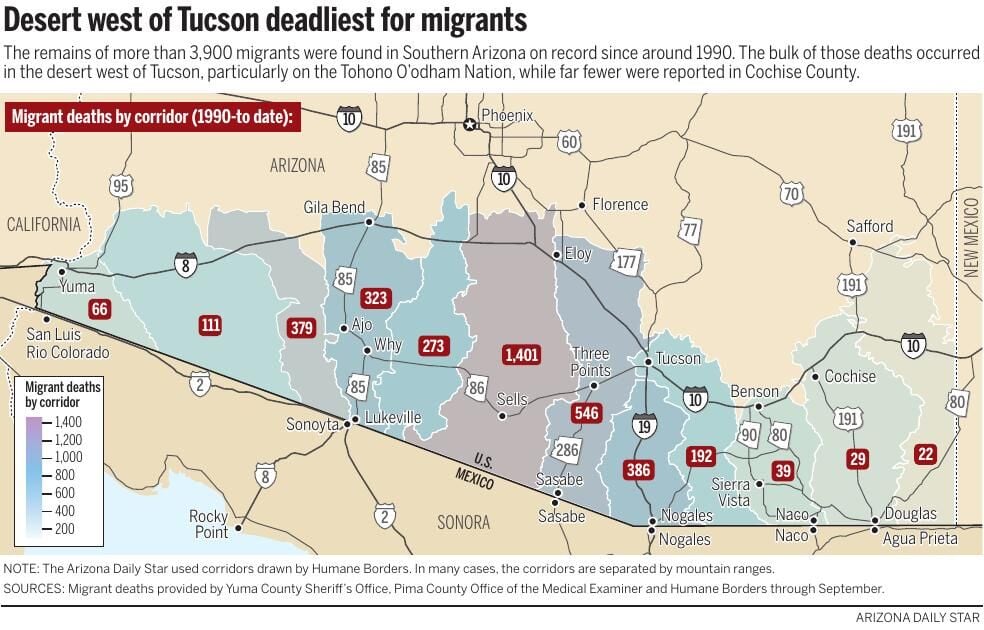

If rescue efforts were to increase, they would not necessarily have to be spread across the length and breadth of Southern Arizona, the Star's geographical analysis of medical examiner data shows. Instead, they could focus on certain cross-border corridors that are the deadliest for migrants. Even within those corridors, large numbers of deaths occur in very specific areas.

Difficult rescues

Local officials sometimes lack the resources to conduct simultaneous searches.

In the case of Jeremias Soto Velazquez, all would-be rescuers knew was that he was last seen near a water tank somewhere south of Little Tucson on the Tohono O'odham Nation reservation.

A Guatemalan man stranded in the Baboquivari Mountains southwest of Tucson is lifted into a helicopter by Border Patrol rescuers in late July.

Soto crossed the border with a group of migrants in May 2020, but he grew ill and eventually fell unconscious. The group left him on the west side of the Baboquivari Mountains. A family member called a hotline run by No More Deaths, who then called the Tohono O'odham Nation Police Department, says an incident report from the tribal police.

But the Tohono O'odham police were busy searching for another missing person elsewhere on the reservation. The next day, Soto's father told No More Deaths volunteers that Soto was left by a water tank or well, but he didn't have Soto's precise location. The report does not say how Soto's father learned that information.

Again, the Police Department did not have any resources available. It wasn't until three days after Soto went missing that those resources became available and police searched for him. They couldn't find him.

The search effort was given a boost after a man in Soto's group returned to where they had left him and brought him water. The man logged the GPS coordinates for Soto's location and passed them to Border Patrol agents when they picked him up. Using those coordinates, a police officer found Soto's body.

In other instances, rescue efforts get tangled up in jurisdictional confusion that costs precious minutes.

On May 6, 2021, two cousins crossed the border southwest of Tucson. They made it all the way to an area west of Marana, but one started to feel sick and the other called 911, according to an incident report from the Pima County Sheriff's Department. Deputies from Pima and Pinal counties, along with officers from the Tohono O'odham Nation Police Department, tried to figure out who had jurisdiction.

A half hour went by and one cousin called 911 again to say the other had stopped breathing. A short time later, Borstar (Border Patrol Search, Trauma and Rescue) agents arrived and tried to treat the cousin, but he had died.

In some cases, humanitarian groups and relatives of a missing migrant must step in when official efforts fail.

During a record-breaking series of 100-degree days in June, four brothers showed up at the Pima County Sheriff's Department to ask about their brother-in-law. He had gone missing after crossing the border through the desert southwest of Tucson.

Their brother-in-law, Carlos Arevalo Gonzalez, crossed the border on June 12 near Sasabe. Border Patrol agents caught the group two days later south of Three Points, about 30 miles southwest of Tucson, but by that time a woman in the group had died, a sheriff's deputy wrote in an incident report.

The Mexican Consulate had informed the brothers that the woman who died, Berta Ladios, was in the group that crossed the border with their brother-in-law. One of the migrants in the group contacted the brothers and told them Arevalo was not doing well after they left Ladios behind when she died. Soon after, the group left Arevalo.

Deputies searched for Arevalo, but couldn't find him. One of the brothers told a deputy that he and volunteers with No More Deaths would search the next day. They followed birds to Arevalo's body, about 30 miles north of the border.

Calling for help

When officials spoke to a crowd of news reporters this spring for an annual border safety event, they tried to send a clear message to any migrants planning to cross the border: Call 911 if you need help. Don't waste precious battery calling your family or anyone else.

Inside a hangar filled with airplanes and helicopters used to rescue migrants at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base, officials from the Border Patrol, Mexican consulate and Guatemalan consulate took turns driving home the message, meant to take advantage of the fact that many migrants carry cellphones when they cross the border.

Deputy Chief Patrol Agent Sabri Dikman urged migrants not to cross the border illegally, saying, "Don't do it. The desert is vast and treacherous."

"To find a person whose only location information is, 'I've been walking for five days' can be nearly impossible," Dikman said. "Even with our best resources, the task can take days."

For migrants who carry a phone, he urged them to call 911: "This is your single best chance for being rescued."

The southern foothills of the Baboquivari Mountains west of Sasabe. “The desert is vast and treacherous,” the Border Patrol’s Sabri Dikman warns migrants contemplating a crossing. “Don’t do it.”

"If you call anyone else, you're wasting your battery. That cellphone battery is your life. Call 911," Dikman said.

Ideally, rescuers would then be able to locate migrants using cellphone towers. In a positive development for rescue efforts, 911 is also now the emergency number in the Mexican state of Sonora, just south of Arizona.

Yet, at the Medical Examiner's Office in Tucson, many of the bags containing property recovered at the scene of a death include at least one cellphone. Incident reports from local law enforcement agencies often mention finding phones and solar battery chargers next to migrants who died in the desert.

While Border Patrol agents, local law enforcement and humanitarian volunteers can respond to hundreds of 911 calls every year, those efforts face an obstacle that no amount of individual effort can overcome: They can't respond to distress calls that are never made.

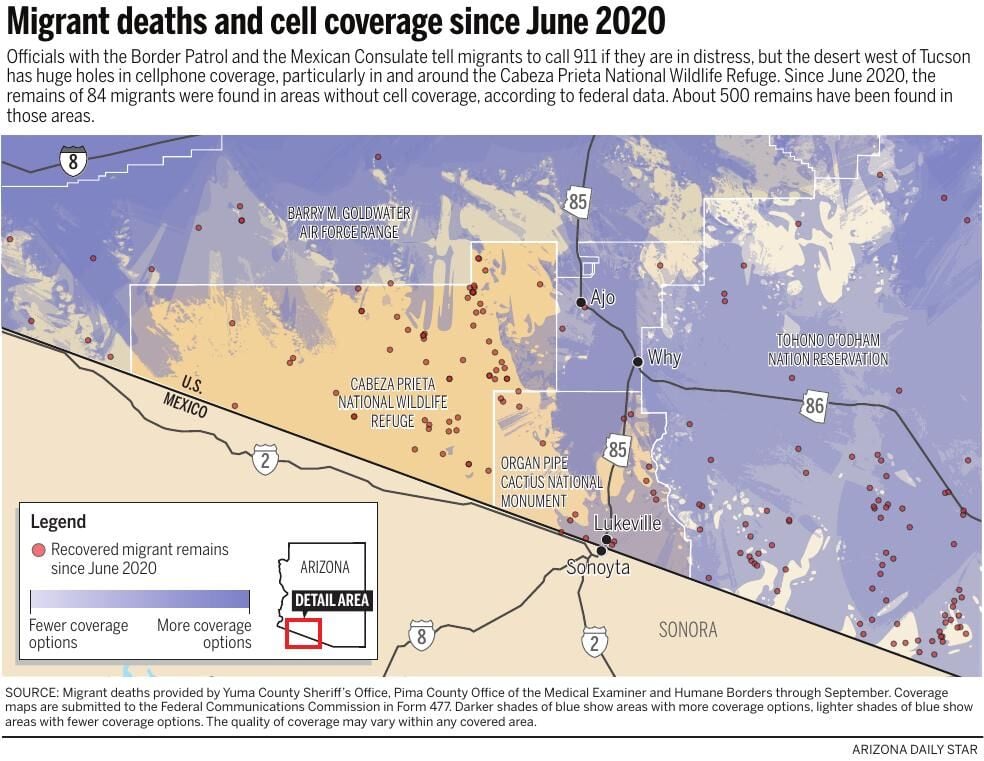

The desert west of Tucson has been one of the busiest areas for border crossings for many years, but vast areas of it either do not have cell coverage of any kind or the coverage is spotty and unreliable, according to coverage maps from the U.S. Federal Communications Commission as of June 2020.

The largest coverage hole is in and around the Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge, one of the deadliest areas for migrants in Southern Arizona. Smaller holes dot the mountain ranges that run north-south across the border.

The remains of 48 migrants were found in areas without cell coverage since the start of 2021. Another 66 sets of remains were found in those areas in 2020, the Star found by comparing data on migrant deaths with cellphone coverage maps from the FCC. The remains of 514 migrants were found in those areas since 2000.

Nearly all the 911 calls the Star reviewed came from the area between Nogales and the eastern portion of the Tohono O'odham Nation reservation.

The only calls from west of the reservation came from humanitarians, ranchers or wildlife officials reporting the discovery of human remains.

Nerve center

The limits created by the lack of cell coverage are clearly visible inside an office on South Swan Road that the Border Patrol uses as its nerve center for rescuing migrants.

A massive 30-foot-long screen dominates one wall, while agents sit in rows of cubicles with phones pressed to their ears. The screen shows a map of Southern Arizona, similar to the topographical maps offered by Google Maps, with icons showing where distress calls came from and how far agents are from arriving at the migrant's location.

The map showed three red icons of telephones on June 17, indicating three distress calls from migrants in the Baboquivari Mountains. Icons for Border Patrol agents slowly moved across the screen toward them.

The Border Patrol’s wall-sized video screen at the Arizona Air Coordination Center shows the location of rescue call stations and active rescues in the Tucson Sector.

The area from the New Mexico state line to the Tohono O'odham Nation reservation was abuzz with icons showing migrants, agents, aircraft and other Border Patrol assets. But much of the desert west of Ajo showed no activity at all.

The lack of cell coverage west of Ajo is a fact that Agent Ryan Riccucci, who leads the rescue efforts from the office, must work around. Simply put: "People can't call for help out in that area," he said.

Even for migrants who are in areas with cellphone reception, the ability to make a call does not guarantee a rescue.

Migrants at a shelter in Nogales, Sonora, said smugglers told them not to turn on their phones because the Border Patrol would be able to track the signal; or that they bought a phone to be able to make calls, but the signal was unreliable.

Calls to the 911 dispatch center at the Pima County Sheriff's Department often were dropped repeatedly, much to the frustration of dispatchers, Border Patrol agents and migrants, the Star found after reviewing roughly 150 calls the Sheriff's Department transferred to the Border Patrol since September 2020.

Deadliest areas

The border counties in Arizona where migrants cross into the U.S. include about 27,500 square miles, or more than three times the size of El Salvador.

But migrant deaths are not spread evenly across that area. Instead, remains are found in a small fraction of it, focused on specific areas west of Tucson, a geographical analysis by the Star shows.

Every year since 2000, at least 50% of the remains were found in less than 8% of those 27,500 square miles; in some years it was as little as 3% of that area.

The concentration of deaths in certain areas could allow more focused rescue efforts to be more successful.

The Star divided Southern Arizona into sections that cover 100 square miles each, and found that deaths tend to cluster in some of the areas. For example, about 50% of all remains found in 2021 were in 16 of these areas, which add up to about 6% of the area in border counties.

Nearly all of these 16 areas are west of Interstate 19. Most overlap the Tohono O'odham Nation reservation. Others overlap the Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge, Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, Barry M. Goldwater Air Force Range and a section of the Coronado National Forest along the border. East of Interstate 19, one area overlaps the San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area.

Using the 12 cross-border corridors established by the aid group Humane Borders, the Star found the corridor west of the Baboquivari Mountains is the deadliest one in 2021, with more than triple the death count of any other corridor.

Within that corridor, many of the deaths are concentrated in smaller areas. A cluster of seven of these areas near Sells, on the Tohono O'odham Nation, accounted for 25% of all deaths in border counties so far in 2021. These seven areas account for less than 3% of the area across Arizona's border counties.

Small measures

As they have done for two decades, local aid groups and the Border Patrol push forward small-scale measures on their own initiatives.

The Border Patrol increased its rescue efforts over the years, although officials are quick to say they must balance efforts to rescue migrants with the agency's primary goal of securing the border.

"Our primary mission is border security, but we are a link in the emergency management system," Riccucci said. When agents get a distress call from a 911 dispatch center, "at that moment the border security mission stops and it becomes purely humanitarian," he said.

The Border Patrol now has an integrated system to relay information about migrants in distress between the Tucson headquarters and agents on the ground and in the air, which Riccucci said has allowed them to respond to twice as many distress calls.

The Tucson Sector's 3,600 agents now include 23 paramedics, 53 Borstar agents, who are specially trained in search and rescue, and more than 230 agents trained as emergency medical technicians.

The Border Patrol set up more than 30 rescue beacons, which have a blue light to make them visible at night. Migrants in distress can push a button on the beacon to alert the Border Patrol that they need help.

Migrants in distress can push a button on one of more than 30 rescue beacons set up by the Border Patrol, but the effectiveness of the beacons remains unclear.

The Border Patrol also placed a half-dozen satellite phones in the desert, akin to roadside assistance phones, and 30 placards migrants can use as reference points when calling 911.

The effectiveness of the rescue beacons is unclear. Tucson Sector officials did not provide data on their use to the Star. The best available data came from a Customs and Border Protection report in February, which said 144 rescues were associated with 67 rescue beacons "in the southwestern section of Arizona" in fiscal 2019.

"At this time, CBP's data systems lack the interoperability and data sets that would enable CBP to track and share specific information associated with migrant rescues with federal, state, and local partners, rescue beacons, 911 placards, location and identification of remains, and cellphone coverage on a large-scale basis," CBP officials said in the report.

A network of humanitarian groups focused on rescues sprang up in Southern Arizona since the early 2000s.

Some areas of the desert in Southern Arizona are now dotted with blue water barrels, maintained by Humane Borders, and small caches of water jugs and food placed on migrant trails by volunteers with No More Deaths, which also runs a camp for migrants in need of medical care near Arivaca, much to the aggravation of Border Patrol officials.

Groups such as Border Angels, Aguilas del Desierto (Eagles of the Desert), Armadillos Busqueda and Rescate (Armadillos Search and Rescue), and Battalion Search and Rescue all search for remains in the desert.

La Coalicion de Derechos Humanos (The Coalition of Human Rights) established a crisis call center to help families find lost loved ones. The Border Patrol runs a similar operation to find missing migrants by coordinating family members, consulates and law enforcement agencies.

The Colibri Center for Human Rights helps families identify lost loved ones, at times by conducting DNA tests. Humane Borders used medical examiner data to build a public database on migrant deaths.

The efforts of these humanitarian groups unfold within tight boundaries built up over the years by federal officials in Arizona.

The Border Patrol and the U.S. Attorney's Office repeatedly cracked down on humanitarian efforts they viewed as crossing the line between helping migrants and aiding human smuggling.

As far back as the 1980s, federal authorities arrested members of the Sanctuary Movement on human-smuggling charges after they offered shelter at churches in Tucson to refugees from Central America.

In the 2000s, as volunteer humanitarian efforts spread into the desert, a federal judge ruled that volunteers could not legally transport migrants in distress to hospitals in Tucson.

In recent years, Border Patrol agents entered No More Deaths' medical camp near Arivaca without permission several times after surrounding the camp with agents and trucks.

Even leaving food and water on migrant trails could be a criminal offense. Fish and Wildlife officials changed regulations on the Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge in the summer of 2017 to prohibit leaving food and water there. Nine No More Deaths volunteers faced federal misdemeanor charges when they disregarded that rule change, citing a humanitarian imperative to help migrants in distress.

The remains of more than 160 migrants were found on or near the Cabeza Prieta refuge since the summer of 2017.

In 2018, No More Deaths volunteer Scott Warren faced felony human-smuggling charges after he let a pair of migrants spend two nights at a No More Deaths aid station in Ajo.

Reminders

of lives lost

One local effort that has become the gold standard along the U.S.-Mexico border is the record-keeping at the Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner.

Over the course of 20 years, the office has built the capacity to quickly and accurately document migrant deaths, director Dr. Greg Hess said.

That effort is guided by the public's interest in migrant deaths, similar to the public's interest in deaths resulting from drug overdoses, suicides, firearms and other causes, he said.

"We try to keep as much detailed, objective information as we can to respond to people's needs to learn about those different types of deaths," Hess said.

The county medical examiner is not required by law to document the deaths of migrants, but it is a task that any civilized country should take on, Hess said.

"There isn't anything that requires one to keep track of this group separately from all the other remains that are reported to you," Hess said. "Legally, the only thing the law says one must do with unidentified remains is report it to the medical examiner's office. That's it."

While Hess keeps the public up to date on deaths in the desert, lockers in a small room down the hall from his office fill up with heartbreaking reminders of the lives lost.

Belongings found on migrants who died in the deserts of Southern Arizona are kept in sealed bags at the Medical Examiner’s Office on Tucson’s south side.

A wallet-sized photo of a little girl with one pigtail tied with a red scrunchie. A water-soaked Bible. Prayer cards and rosaries. A receipt for a refrigerator. School records. Marriage records. A business card for a Tucson immigration lawyer. Pages of handwritten phone numbers. Letters to loved ones.

“My love, I know we are not a perfect couple but I love you," read a letter found among the property of one woman who died.

"I’ve always told you that you are the love of my life and you really are important in my life," she wrote in Spanish. "I know that sometimes I’m not the woman that you wanted in your life and the truth is that I know you sometimes get bored with me for how I am. I love you and I thank you for staying by my side in spite of everything.”

Day after day, the remains of the people who carried those items and wrote those words are wrapped in white plastic sheets and placed in the cooler, waiting for their loved ones to claim them.

At an office on South Swan Road in Tucson, a Border Patrol agent talks to a group of five lost somewhere in the Baboquivari Mountains. The corridor west of that mountain range has triple the death count of any other area this year in Arizona’s borderlands.