Raúl Grijalva’s political career began not on the stump, but on the streets, marching, picketing and organizing his way into the spotlight.

In the early 1970s, he was a member of La Raza Unida, a Chicano-based political party born out of dissatisfaction with the issues emphasized by Democrats and Republicans. He was an early supporter of grape and lettuce boycotts organized by the legendary California activist Cesar Chavez and his collaborator Dolores Huerta of the United Farm Workers.

Grijalva and his wife Mona were also early supporters of the Manzo Area Council, an anti-poverty and immigrant rights activist group headquartered in Barrio Hollywood on Tucson’s west side. He was a frequent critic of the Vietnam War and he and other Chicano activists at the time helped spark a student walkout at Pueblo High School in the late 1960s.

A student who joined that walkout was Isabel Garcia, today a leading Tucson activist for immigrant rights, back then a high school student and daughter of a union organizer and Democratic precinct committeeman, Rodolfo Garcia, who later helped nudge Grijalva into electoral politics.

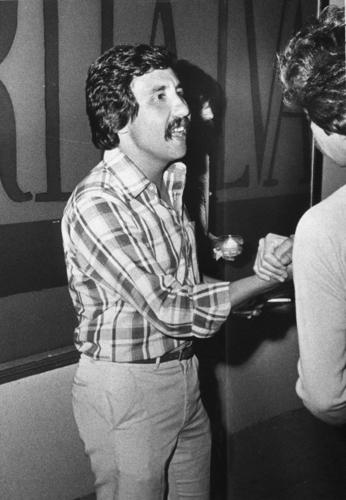

Tucson Unified School District board member Raúl Grijalva in 1978.

After the walkout, Isabel Garcia later joined her father, along with Grijalva, fellow Latino activist Sal Baldenegro and others, in picketing the Pickwick Inn, a longstanding south-side restaurant that was one of the last remaining segregated Tucson restaurants. Later, the restaurant relented and eventually got new ownership by a Latino family, becoming the Silver Saddle Steakhouse.

Grijalva was also an early supporter of MECHA, short for Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán, a group formed in 1968 when 10,000 or so students walked out of a dozen East Los Angeles high schools in protest of what they deemed a racist educational system.

The group’s causes spread to Southern Arizona, when an unrelated Hispanic group at the University of Arizona submitted a list of demands to UA administrators calling for increased recruitment and retention efforts of Hispanic students. That group and dozens of other Hispanic organizations merged into a local MECCA chapter, then-Arizona Daily Star columnist Ernesto Portillo Jr. wrote in 1998.

In the 1960s and '70s, "we were dealing with the issue of representation for all Chicanos," Grijalva, by then a Democratic Pima County supervisor, told Portillo. "Almost everything we did was confrontational and loud, but it was a means to an end and we got things done."

So diverse and so fragmented were the various activist movements back then that he first felt they seemed unrelated and disjointed, Grijalva, by then a congressman, told a Tucson Weekly interviewer in 2006.

"But suddenly, it was like a light went on,” Grijalva recalled. “I realized that the struggles of the UFW were related to the other movements. People were trying to make the world a better place for themselves, for their families and for others. The more I read, the more I understood the significance of the struggle and the rightness of it all."

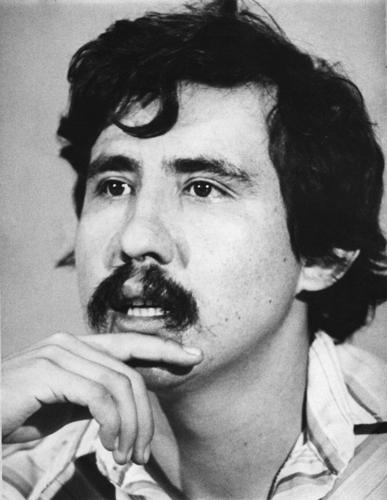

Tucson Unified School District board member Raúl Grijalva in 1977.

Richard Miranda, a former Tucson city manager and police chief, was a freshman at Sunnyside High School when Grijalva was a senior there in the 1960s, and got to know him somewhat when the two were UA students.

“I’d see him take leadership roles on issues and that made a big impression on me,” Miranda recalled shortly after Grijalva's March 13 death, at age 77, of complications from lung cancer treatment while serving his 12th term in Congress. “We were from the same neighborhood. He seemed so articulate and intelligent on these issues.

“Watching him and just observing him take a leadership role in the community really inspired me. ... It was amazing to me — a kid from Sunnyside becoming a congressman,” Miranda recalled.

"Raúl was there every moment"

Grijalva in 1972 ran for the governing board of Tucson Unified School District and lost, but ran again two years later and won. One of his prime missions was clear: to improve the educational lot of Chicanos and other Mexican-Americans.

A Latino hadn’t sat on the TUSD board for 23 years before Grijalva was elected, the Arizona-Sonora News reported in 2017. Prior to his arrival, "there was never a Chicano perspective” at the district or on the board, Margo Cowan, who was director of the Manzo Area Council, recalled. ”Chicano and Chicana students were seen as statistics. There was never, heaven forbid, Chicano studies, or Mexican holidays, or an understanding of what the holidays stood for. There was never Spanish spoken in school.

“He was the first one who came from (the Mexican-American) community and lived the experiences of community,” Cowan said.

He joined a school board waist-deep in controversy and litigation over school desegregation — litigation that only recently has been settled. While he did for a time support busing at certain schools to achieve racial balance, Grijalva’s longer-lasting contribution was to push successfully to create “magnet schools” of high enough quality that whites and Latinos would want to attend them.

He also pushed successfully to create programs that would help lower-achieving Latinos, African-Americans, Native Americans and other ethnic minorities improve their educational outcomes, recalled Tom Castillo, who served on the board with Grijalva during the 1980s.

“We kept working on it to get the administration to solve that. That is a never ending task,” Castillo recalled.

Board member Grijalva jumped hard and publicly into the immigration issue in 1976, when the U.S. Attorney’s Office raided Manzo Area Council headquarters and filed charges against the council for “transporting, harboring and assisting” undocumented immigrants entering the U.S., Garcia recalled. The charges were later dropped.

“We went and picketed the prosecutor’s house. Grijalva was there on the scene,” recalled Garcia, now a leader of the activist group Derechos Humanos. “Raúl was there every moment. He was a champion of immigrants’ rights from the beginning.”

"He put all those pieces together"

Joining the Pima County Board of Supervisors in 1989, Grijalva expanded his horizons to issues of zoning and preservation of desert habitat from development. Through the middle 1990s, he was usually one of two votes on the five-member board to oppose a wave of rezonings that opened up much of the ironwood forest on the Tucson area's northwest side to subdivisions of four houses per acre and up.

Later, when he was joined on the board by more sympathetic colleagues, he was a prime mover in crafting the Sonoran Desert Conservation Plan to buy and preserve hundreds of thousands of acres of desert on the county’s fringes. His most noteworthy contribution, however, may have been his efforts to save Canoa Ranch south of Green Valley, where he was raised as a child and later mastered the art of compromise.

During World War II, Canoa Ranch participated in the U.S. government’s Bracero Program, which allowed the owners to employ immigrant Mexican workers to help offset the loss of American ranch labor serving in the armed forces. One of the workers, Raúl Noriega Grijalva, lived there. His son, Raúl M. Grijalva, was born in the U.S. in February 1948 and lived at the ranch until he was about 5 years old.

Fifty-one years later, Grijalva led a successful effort to block a big developer’s plan to build 6,100 homes, golf courses and a hotel on the ranch's 6,000 acres. But in the end, he accepted a compromise deal in 2001 to allow 2,000 homes on part of the ranch while the county bought the remaining 4,800 acres — a deal that ended a six-year dispute.

Grijalva said he decided to compromise because he feared more delay could allow a future board to approve a bigger development, or let Green Valley incorporate and approve one.

Since then, the county has steadily restored the ranch’s historic buildings and drilled a well to bring back a recreational lake that existed during the 1930s and ‘40s. It's now called the Raul M. Grijalva Canoa Ranch Conservation Park.

“He understood how to put together a coalition of environmentalists, homeowners, men of faith and labor. That coalition has served many many people, not just him. But he put all those pieces together,” recalled Christina McVie, a longtime Tucson-area activist who worked closely with Grijalva for decades.

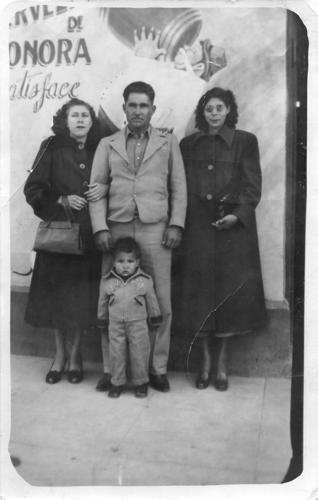

Congressman Raúl Grijalva who was born on historic Canoa Ranch in Pima County. This photo shows him his father, Raúl Grijalva, his mother Rafaela Grijalva, and his mother's sister, Sara Martinez. Grijalva is about 3 years old.

Something she most admired about Grijalva was that he was not like many politicians who tell their constituents what they want to hear, she said.

“He would come up to me and say ‘Christina, you’re not going to like this. But here’s the deal.’”

"You can achieve great things"

On entering Congress, his vision expanded again, particularly in the conservation arena.

Grijalva quickly took up the not always popular cause of fighting global warming, and in his last years strongly backed President Joe Biden's Inflation Reduction Act, which funneled tends of billions of dollars into programs to build or grant incentives to sell heat pumps, electric vehicles, solar energy farms and household solar panels, to name a few.

The Tucson congressman spent 17 years successfully pushing to create a national monument north and south of Grand Canyon National Park to preserve 917,000 acres of public lands, and countless tribal artifacts and other cultural resources. Biden designated the Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni-Ancestral Footprints of the Grand Canyon National Monument in 2023, over objections of some companies that had wanted some of the land opened to uranium mining..

"What Grijalva showed us is that with persistence, fortitude and some degree of patience, you can achieve great things," said Ethan Aumack, executive director of the Grand Canyon Trust, a conservation group that pushed for the monument's creation.

Grijalva also fought hard against the proposed Rosemont Mine in the Santa Rita Mountains, which was later stopped in federal court, and a separate proposal by Resolution Copper to build a larger copper mine at Oak Flat near Superior. While the Resolution proposal remains active and the Rosemont Mine has morphed into the Copper World Mine to Rosemont's west, Grijalva did have a major conservation success in getting the Great American Outdoors Act passed during the Biden Administration.

That act for the first time provided a guaranteed annual source of $900 million in federal cash for land acquisition efforts through the federal Land and Water Conservation Fund. It also has provided hundreds of billions of dollars annually for improving infrastructure such as water pipes, visitor center upgrades, bridge repairs and the like.

At the same time, Grijalva pushed hard to get money funneled into his district to build infrastructure, recalled Miranda and Ana Ma, who was chief of staff during Grijalva's first six years in Congress.

"He was very instrumental in getting the streetcar to Tucson," recalled Miranda, noting that a streetcar stop across from the Mercado San Augustin Plaza was named after him.

Grijalva obtained money for a new, $400 million port of entry for the city of Douglas on the Mexican border whose construction will be starting soon, Ma said. He also helped obtain money to upgrade the often damaged and leaky Nogales International Outfall Interceptor, an 8.5-mile wastewater pipeline from the Mexican border to the Nogales International Wastewater Treatment Plant in the U.S.

He also helped get federal money to upgrade water infrastructure in Tolleson near Phoenix at his district's northwestern edge, Ma said.

Speaking on a personal note, Miranda recalled that in August 2015, his father-in-law Tony Figueroa was in ill health and wasn't expected to live much longer. When family members looked through Figueroa's old military records, they learned he was supposed to have received two medals for his Navy service on Midway Island during World War II. But when asked about the medals, Figueroa told the family he never received them, Miranda said.

Congressman Raúl Grijalva, left, hugs his daughter, Adelita Grijalva, as they wait for election results on Nov. 2, 2010. Adelita was running for a seat on the Tucson Unified School District board.

"We contacted Raúl’s office about the matter. He looked into it and the Navy acknowledged that the medals were never served. Raúl advocated for the medals to be served to my father-in-law. And when they were received Raúl himself came to a luncheon we held for my father-in-law, and pinned the medals on him," Miranda said.

Four months later, Figueroa died.

Photos: Congressman Raúl Grijalva's memorial services

Congressman Raúl Grijalva's funeral mass

Updated

Ramona Grijalva, second from left, smiles at a friend as she leads her family into St. Augustine Cathedral, 192 S. Stone Ave. for her late husband’s, Congressman Raúl Grijalva’s, funeral mass in Tucson, Ariz. on March 26, 2025.

Congressman Raúl Grijalva's funeral mass

Updated

Adelita Grijalva, second from left, holds hands with Dolores Huerta, far left, as they walk in for her father’s, Congressman Raúl Grijalva’s, funeral mass at St. Augustine Cathedral, 192 S. Stone Ave. in Tucson, Ariz. on March 26, 2025.

Congressman Raúl Grijalva's funeral mass

Updated

Raquel Grijalva, center, daughter of Congressman Raúl Grijalva walks with family into the funeral mass at St. Augustine Cathedral, 192 S. Stone Ave. in Tucson, Ariz. on March 26, 2025.

Congressman Raúl Grijalva's funeral mass

Updated

An urn filled with the remains of Congressman Raúl Grijalva sits on the floor of a sports utility vehicle awaiting to be carried into a funeral mass at St. Augustine Cathedral, 192 S. Stone Ave. in Tucson, Ariz. on March 26, 2025.

Congressman Raúl Grijalva's funeral mass

Updated

A member of the honor guard holds an urn filled with the remains of Congressman Raúl Grijalva at the beginning of a funeral mass outside of St. Augustine Cathedral, 192 S. Stone Ave. in Tucson, Ariz. on March 26, 2025.

Congressman Raúl Grijalva's funeral mass

Updated

Emeritus Bishop Gerald F. Kicanas, right, leads the honor guard out of St. Augustine Cathedral, 192 S. Stone Ave. following a funeral mass for Congressman Raúl Grijalva in Tucson, Ariz. on March 26, 2025.

Congressman Raúl Grijalva's funeral mass

Updated

Emeritus Bishop Gerald F. Kicanas, lower left, leads the honor guard out of St. Augustine Cathedral, 192 S. Stone Ave. following a funeral mass for Congressman Raúl Grijalva in Tucson, Ariz. on March 26, 2025.

Congressman Raúl Grijalva's funeral mass

Updated

Mourners arrive for Congressman Raúl Grijalva’s funeral mass outside of St. Augustine Cathedral, 192 S. Stone Ave. in Tucson, Ariz. on March 26, 2025.

Congressman Raúl Grijalva's funeral mass

Updated

Members of the honor guard carry out a folded American flag and the urn filled with the remains of Congressman Raúl Grijalva following a funeral mass at St. Augustine Cathedral, 192 S. Stone Ave. in Tucson, Ariz. on March 26, 2025.

Congressman Raúl Grijalva's funeral mass

Updated

A young mourner is comforted as she leaves a funeral mass for Congressman Raúl Grijalva at St. Augustine Cathedral, 192 S. Stone Ave. in Tucson, Ariz. on March 26, 2025.

Congressman Raúl Grijalva's funeral mass

Updated

Mourners sit during a funeral mass for Congressman Raúl Grijalva at St. Augustine Cathedral, 192 S. Stone Ave. in Tucson, Ariz. on March 26, 2025.

Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez

Updated

Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) speaks on the impact of Congressman Raúl Grijalva’s mentorship during a funeral mass at St. Augustine Cathedral, 192 S. Stone Ave. in Tucson, Ariz. on March 26, 2025.

Rep. Nancy Pelosi

Updated

Speaker Emerita Rep. Nancy Pelosi speaks on the impact of Congressman Raúl Grijalva’s work on the nation during a funeral mass at St. Augustine Cathedral, 192 S. Stone Ave. in Tucson, Ariz. on March 26, 2025.

Deb Haaland

Updated

Former Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland speaks on the impact of Congressman Raúl Grijalva’s work on the environment and Indigenous and tribal advocacy during a funeral mass at St. Augustine Cathedral, 192 S. Stone Ave. in Tucson, Ariz. on March 26, 2025.

Congressman Raul M. Grijalva celebration of life

Updated

Guests dance during the celebration of life for Congressman Raúl M. Grijalva at El Casino Ballroom, 437 East 26th Street, Tucson, Ariz., March 26, 2025.

Congressman Raul M. Grijalva celebration of life

Updated

Supervisor Adelita Grijalva, middle, chants “Sí se puede” during the celebration of life for her father, Congressman Raúl M. Grijalva at El Casino Ballroom, 437 East 26th Street, Tucson, Ariz., March 26, 2025.

Congressman Raul M. Grijalva celebration of life

Updated

Dolores Huerta, a life-long civil rights activist and friend of Congressman Raúl M. Grijalva speaks during his celebration of life ceremony at El Casino Ballroom, 437 East 26th Street, Tucson, Ariz., March 26, 2025.

Congressman Raul M. Grijalva celebration of life

Updated

Supervisor Adelita Grijalva hugs people during the celebration of life for Congressman Raúl M. Grijalva at El Casino Ballroom, 437 East 26th Street, Tucson, Ariz., March 26, 2025.

Congressman Raul M. Grijalva celebration of life

Updated

Memoriam stickers available during the celebration of life for Congressman Raúl M. Grijalva at El Casino Ballroom, 437 East 26th Street, Tucson, Ariz., March 26, 2025.

Congressman Raul M. Grijalva celebration of life

Updated

A line forms to greet Supervisor Adelita Grijalva during the celebration of life for her father, Congressman Raúl M. Grijalva at El Casino Ballroom, 437 East 26th Street, Tucson, Ariz., March 26, 2025.

Congressman Raul M. Grijalva celebration of life

Updated

Los Gallegos perform during the celebration of life for Congressman Raúl M. Grijalva at El Casino Ballroom, 437 East 26th Street, Tucson, Ariz., March 26, 2025.

Congressman Raul M. Grijalva celebration of life

Updated

Ramona (Mona) Grijalva, the wife of the late Raúl M. Grijalva laughs during the celebration of life for the Congressman at El Casino Ballroom, 437 East 26th Street, Tucson, Ariz., March 26, 2025.

Congressman Raul M. Grijalva celebration of life

Updated

Memoriam stickers and candles available during the celebration of life for Congressman Raúl M. Grijalva at El Casino Ballroom, 437 East 26th Street, Tucson, Ariz., March 26, 2025.

Congressman Raul M. Grijalva celebration of life

Updated

Hundreds attend the celebration of life for Congressman Raúl M. Grijalva at El Casino Ballroom, 437 East 26th Street, Tucson, Ariz., March 26, 2025.

Congressman Raul M. Grijalva celebration of life

Updated

Hundreds attend the celebration of life for Congressman Raúl M. Grijalva at El Casino Ballroom, 437 East 26th Street, Tucson, Ariz., March 26, 2025.

Photos: U.S. Rep. Raúl Grijalva 1948 — 2025

Raúl Grijalva, 1980

Updated

Tucson school board member Raúl Grijalva at historic Carrillo School in 1980.

Raúl Grijalva

Updated

Congressman Raúl Grijalva who was born on historic Canoa Ranch in Pima County. This photo shows him his father, Raúl Grijalva, his mother Rafaela Grijalva, and his mother's sister, Sara Martinez. Grijalva is about 3 years old.

Raúl Grijalva, 1967

Updated

Raúl Grijalva, shown his senior year at Sunnyside High School's 1967 yearbook. He wasn't active in any high school clubs or student government and didn't even use his given name because teachers had difficulty pronouncing it. When he was in college, he found his future calling after joining MEChA, a student Chicano activist group.

Raúl Grijalva, 1974

Updated

A U.S. District Court lawsuit filed against Tucson School District One Board of Trustees lies before members of minority groups explaining their battle for minority representation on the school board on March 28, 1974. At right is Raúl Grijalva and beside him is Mary Mendoza, chairman of the Mexican-American for Equal Opportunity, two of the plaintiffs in the suit.

Raúl Grijalva, 1977

Updated

Tucson Unified School District board member Raul Grijalva in 1977.

Raúl Grijalva, 1977

Updated

Tucson Unified School District board member Raúl Grijalva in 1977.

Raúl Grijalva, 1978

Updated

Tucson Unified School District board members Raúl M. Grijalva and Soleng Tom at the desegregation press conference in 1978.

Raúl Grijalva, 1978

Updated

Tucson Unified School District board member Raúl Grijalva in 1978.

Raúl Grijalva, 1980

Updated

Tucson school board member Raúl Grijalva at historic Carrillo School in 1980.

Raúl Grijalva, 1986

Updated

Raúl Grijalva, at the site of Hohokam Middle School at 7400 S Settler Ave., as it was being built on November 25, 1986. Grijalva was in the process of leaving the Tucson Unified School School Board and becoming a member of the Pima County Board of Supervisors.

Raúl Grijalva, 1986

Updated

Tucson Unified School District Chairman Raúl Grijalva pauses as he reads to a class at Wakefield Jr High School on February 13, 1986.

Raúl Grijalva, 1988

Updated

Raul Grijalva after winning a seat on the Pima County Board of Supervisors in November, 1988.

Raúl Grijalva, 1996

Updated

Raúl Grijalva stands in the doorway of his campaign headquarters on S. 12th ave. on election night, Sept. 10, 1996, as he awaits results in the District 5 race for Pima County Supervisor.

Raúl Grijalva, 1997

Updated

Raúl Grijalva listens during the Pima County Interfaith Council Economic Summit at El Pueblo Neighborhood Center in 1997.

Raúl Grijalva, 2000

Updated

(From Left) Leonard Basurto, Director of Bilingual Education for TUSD, Raúl Grijalva, Pima County Board of Supervisors, Elena Parra, Parent and Clinical Psychologist, and Sheilah Nicholas, UA Department of American Indian Studies, discuss their personal experiences concerning bilingual education as well as their stand towards Proposition 203 in 2000. Proposition 203 on the November ballot would virtually eliminate bilingual education in Arizona and replace it with an all-English "immersion" program for children whose English is limited.

Raúl Grijalva, 2002

Updated

Raúl Grijalva, running for U.S. Congressional District 7, is congratulated by Richard Elias, currently a Pima County Supervisor, during the Democratic primary in September, 2002.

Raúl Grijalva, 2002

Updated

U.S. Congressman-elect, Raúl Grijalva gives a phone interview while his campaign manager Ana M. Ma drives to the Grijalva Elementary School to speak to students the day after the election Nov. 11, 2002.

Raúl Grijalva, 2002

Updated

Arizona Senator Jon Kyl, U.S Rep-elect Raúl Grijalva and US Rep. Jim Kolbe listen to US Department of Transportation Inspector Jose Rivas explain the function of the hand held computer which brings up the status and vital information on commercial vehicles which pass this check-pint at the Mariposa Port of Entry west of Nogales on Dec. 5, 2002.

Raúl Grijalva, 2002

Updated

U.S. Congressman-elect, Raúl Grijalva starts to show his lack of sleep while talking on the phone the day after the election on Wednesday, Nov. 11, 2002.

Raúl Grijalva, 2003

Updated

Rep. Raúl Grijalva, D-Ariz., accompanied by his wife Ramona, takes a mock House oath from House Speaker Dennis Hastert on Capitol Hill, Tuesday, Jan. 7, 2003, in Washington, after the House was officially sworn in to the 108th Congress.

Raúl Grijalva, 2003

Updated

US Sen John McCain, left, and Congressman Raúl Grijalva tour the border crossing at the Mariposa port of entry in Nogales, Ariz., on Friday, Mar 14, 2003, with Undersecretary of Homeland Security Asa Hutchinson to assess efforts to tighten the border and deter terrorist and radiological and weapon infiltration.

Raúl Grijalva, 2004

Updated

U.S. Rep. Raúl Grijalva, a University of Arizona alumnus, delivered the commencement address at UA on Dec. 18, 2004. He challenged the graduates to rise to the challenges of today's world.

Raúl Grijalva, 2005

Updated

U.S. Congressman Raúl Grijalva talks with workers at the Mission Mine outside Tucson, Ariz., as they strike against ASARCO for unfair labor practices on Thursday, July 7, 2005. The congressman was their to offer support for their efforts.

Raúl Grijalva, 2008

Updated

United States Representative Raúl Grijalva, speaks during a press conference on Tumamoc Hill on August 22, 2008 in Tucson, Ariz. El Paso Natural Gas has agreed to test its pipeline under Tumamoc by using a less environmentally destructive plan. The company is required to do pipeline testing, but as opposed to digging up the 1,800 feet of gas line under Tumamoc, it will use small track hoes to unearth small segments.

Raúl Grijalva, 2009

Updated

U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan, second from left, stands in a 4th and 5th grade classroom at Ochoa Elementary School with the school's principal, Heidi Aranda, far left, and Congressman Raúl Grijalva in 2009. Secretary Duncan was at the school to meet with educators and elected officials as part of his Listening and Learning tour.

Raúl Grijalva, 2009

Updated

Frank Y. Valenzuela, left, executive director of the Community Investment Corporation, talks with U.S. Congressman Raúl Grijalva and Ana M. Ma before a presentation to group of small business owners in the Proscenium Theatre at Pima Community College on Tuesday, June 30, 2009, in Tucson, Ariz.

Raúl Grijalva, 2010

Updated

Congressman Raúl Grijalva hugs his daugher, Adelita Grajalva, as they wait for election results at the Grijalva headquarters on South Stone Ave. on November 2, 2010. Adelita was running for TUSD School Board.

Raúl Grijalva, 2011

Updated

Congressional Progressive Caucus co-chair, Rep. Raúl Grijalva, D-Ariz., center, expresses his disapproval of the debt ceiling agreement during a news conference on Capitol Hill in Washington, Monday, Aug. 1, 2011. Listening at back are Rep. Barbara Lee, D-Calif., left, and Rep. Maxine Waters, D-Calif.

Raúl Grijalva, 2011

Updated

U.S. Congressman Raúl Grijalva, right, congratulates Ward 1 councilwoman Regina Romero, left, after she won her primary race,Tuesday, August 30, 2011, at the Riverpark Inn at 350 S. Freeway.

Raúl Grijalva, 2011

Updated

Arizona Governor Jan Brewer and Rep. Raúl Grijalva await the arrival of President Barack Obama and first lady Michelle Obama on Wednesday, Jan. 12, 2011 at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base. The Obamas are in Tucson, Az. to attend a memorial service at the University of Arizona for the six people who died in Saturday's mass shooting that left Rep. Gabrielle Giffords, D-Ariz. in critical condition.

Raúl Grijalva, 2013

Updated

Members of the Congressional Border Caucus, l-r, Congressmen Raúl Grijalva AZ, Beto O'Rourke (TX), and Filemon Vela (TX) talk with reporters at a press conference following an Ad Hoc hearing on immigration held at the Board of Supervisors Hearing Room, 2150 N Congress Dr. in Nogales, Ariz. on Friday, September 13, 2013.

Raúl Grijalva, 2014

Updated

US Rep. Raúl Grijalva, center, laughs as a plaque with his image is uncovered at the western-most stop of the streetcar line as dignitaries and city officials attend the dedication via the streetcar on Monday, July 21, 2014.

Raúl Grijalva, 2016

Updated

U.S. Representative Raúl Grijalva introduces U.S. Sen. Bernie Sanders during a Future to Believe In Tucson Rally on March 18, 2016 at the Tucson Convention Center, 260 S. Church Ave.

Raúl Grijalva, 2016

Updated

Rep. Raúl Grijalva, D-Ariz., right, and other Democrat members of Congress, participate in sit-down protest seeking a a vote on gun control measures, Wednesday, June 22, 2016, on the floor of the House on Capitol Hill in Washington.

Raúl Grijalva, 2013

Updated

Rep. Raúl Grijalva, D-Ariz., center, joins immigration reform supporters as they block a street on Capitol Hill in Washington, Thursday, Aug. 1, 2013, during a rally protesting immigration policies and the House GOP’s inability to pass a bill that contains a pathway to citizenship.

Raúl Grijalva, 2016

Updated

Rep. Raul Grijalva, D-Ariz., speaks during the first day of the Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia , Monday, July 25, 2016.

Raúl Grijalva, 2017

Updated

From left, Rep. Sander Levin, D-Mich., Rep. Raul Grijalva, D-Ariz., Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., Rep. Lloyd Doggett, D-Texas, and Sen. Debbie Stabenow, D-Mich. gather after GOP leaders announced they have forged an agreement on a sweeping overhaul of the nation's tax laws, on Capitol Hill in Washington, Wednesday, Dec. 13, 2017.

Raúl Grijalva, 2024

Updated

Rep. Raúl Grijalva, D-Ariz., leaves a meeting of House Democrats on Capitol Hill, Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, in Washington.

Office Space: Raúl Grijalva's Little Tucson