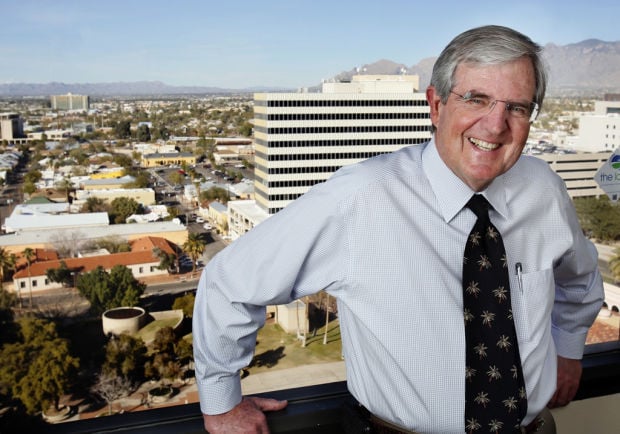

His critics call him “King Huckelberry” or simply, “King Chuck.”

For the last 20 years, the kid from Flowing Wells — whose first tour of Pima County was inside his father’s milk truck — has been the county’s top bureaucrat, earning both the respect and the ire of the community.

Chuck Huckelberry, 64, has been at the center of some very public battles as he attempted to carry out the will of the Board of Supervisors. A short list includes fights with developers and environmentalists, the cities of Marana and Tucson, the Arizona Legislature and even Gov. Jan Brewer, who signed off on a “forensic audit” in 2012 of the county’s 1997, 2004 and 2006 general obligation bonds.

Registered to vote as an independent, Huckelberry has been the target of both Democrats and, more recently, Republicans, who have actively folded calls for his firing into their political rhetoric.

His two decades as county administrator have been colored by difficult political decisions, including dumping the Pima Health Plan health-maintenance organization; selling Posada del Sol, the county nursing home; and contracting with an outside group to run Kino Hospital, all leading to massive downsizing of the county Health Department.

Many of his decisions have hit close to home — some very close. Unlike many hired guns brought in to run large governments, Huckelberry is a lifetime Tucsonan. He was a star football player at Flowing Wells High School who lived most of his life just up the road from the school despite the neighborhood’s long-running decline and even though his six-figure salary would have allowed him to live pretty much anywhere.

It wasn’t until a couple of years ago that he and his wife finally moved into a custom home in the Foothills.

While he’s moved farther from his childhood home, he remains driven to serve his hometown. He hatches big ideas he thinks will make Tucson better and throws himself into seeing them through — sometimes despite the consequences. His singular dedication to creating the Sonoran Desert Conservation Plan, perhaps the hallmark of his career, put him at odds with the area’s powerful developers.

And his determination to improve traffic flow held steady even when it affected his own parents. A county project to widen Wetmore Road forced them out of the 1,200-square-foot home where Huckelberry grew up. The house was torn down in the name of progress.

An environmentalist

A civil engineer with two degrees from the University of Arizona, Huckelberry won’t likely be remembered for the roads he built, the aging facilities he modernized or the multimillion-dollar stadiums he created.

Instead, the affable engineer might better be known decades from now as a born-again environmentalist who helped to preserve the equivalent of 319 square miles of desert.

In his last two decades as county administrator, the county has acquired more than 200,000 acres to be set aside for permanent conservation. It has simultaneously persuaded developers to set aside open space, purchased undeveloped land for flood-control purposes and entered into long-term grazing leases on state trust land and federal land associated with ranches.

Don Diamond had clashed with county officials — including Huckelberry — since the late 1980s as he spearheaded the building of tens of thousands of homes, including those in the controversial Rocking K master-planned community.

The successful developer concedes he initially fought Huckelberry on zoning issues, unwilling to embrace the concept that the environment would be a selling point to would-be home buyers.

“The words ‘open space’ used to scare me,” Diamond says. “I learned, with Chuck’s help and some of the environmentalists we work with, that you can have a better process and do better financially.”

That’s not to say getting there was easy. Police had to shut down one early zoning hearing because of an unruly mob outside.

Eventually though, Diamond developed a lasting admiration and respect for Huckelberry, whom he calls a virtual walking library. The administrator can recall figures from memory and knows issues down to the smallest detail. He can recite on demand facts such as how many endangered Pima pineapple cacti county officials found on a recent survey of the 3.9-mile road extension near Raytheon Missile Systems. (There were four.)

Diamond says Huckelberry is always fair — and he expects the same of his adversaries. When Diamond tried to push back on an existing agreement, he says, he was met with stiff resistance.

“The one thing I’ve learned is not to cross him,” Diamond says. “If you deliver, you’re golden. But if you fail, this guy doesn’t forget.”

Carolyn Campbell, executive director of the Coalition for Sonoran Desert Protection, concedes she and Huckelberry have had some run-ins over the Sonoran Desert Conservation Plan.

To date, the county policy calling for protection of up to 1 million acres has not been tested, as the recent recession has curbed many large building projects in county-controlled areas.

Campbell says Huckelberry has staked large amounts of political capital on backing policies designed to protect open space and wildlife as well as curb private development of environmentally sensitive land.

He earned her respect, even though some were skeptical of a man who got his start at the county by cementing river banks and clearing stretches of virgin desert for new roads.

Congenial style

Huckelberry’s return to Pima County 20 years ago, after leaving briefly in the wake of one of the county’s most disruptive and expensive periods of turmoil, nourished his evenhanded, affable style.

The 1992 election of Ed Moore, Paul Marsh and Mike Boyd — giving the Board of Supervisors a rare Republican majority, set off a chain of events that would lead to 13 people, including the county manager, being fired or demoted.

Moments after being sworn into office on Jan. 4, 1993, the Moore-led majority fired County Manager Enrique Serna and installed Manoj Vyas, once one of Serna’s assistants, in a newly retitled position of county administrator.

As that Republican-controlled board conceived it, the new name signaled a de-emphasis in the position, with more power shifting to the board. In the ensuing decades Huckelberry has demonstrated titles are secondary to how you do the job.

Huckelberry, a deputy manager before the coup, lasted only four months as a deputy administrator under Vyas before leaving to take a consulting job, eventually taking the top spot at Metro Water.

It was a period dominated by turmoil, which started to subside only when Boyd sided with the two Democrats on the board, Raúl Grijalva and Dan Eckstrom, to offer an interim position to Huckelberry, who over 19 years had risen through the ranks to head the county Transportation Department before moving over to the county manager’s office.

The Republican-ordered reorganization in 1993 would eventually cost the county $3.25 million in settlements with seven county officials who were fired or demoted.

While his critics saddle him with the “King Huckelberry” moniker to reflect the immense political power he has built over the last two decades, the man called “Chuckleberry” by his high school peers tells a different story.

Yes, he has been known to dictate 20 memos or more over a weekend. But he also is a regular guy.

Before moving out of his home in the Flowing Wells neighborhood, Huckelberry would bring fruit from his garden in to work to share with colleagues.

These days, he is a common sight biking throughout town with close friends on the weekend.

He was also been known to invite staffers and their families to spend the Thanksgiving or Easter break in Mexico with him and his wife.

Bronson a convert

Supervisor Sharon Bronson once was the architect of an attempt to replace Huckelberry. After the 1996 election, she wanted to make a change in leadership to reflect the new Democratic majority.

But Pima County has prospered under Huckelberry’s watch, Bronson says, specifically noting how well the county weathered the recent recession. The five-term supervisor concedes that few people could have done the job as well as Huckelberry has over his two decades in office.

One of Huckelberry’s biggest feuds is with former Supervisor Moore. The two clashed badly over the fate of the 72-year-old Rillito Racetrack. Moore has sued Pima County officials to keep them from tearing down the horse track and replacing it with athletic fields.

Recently, Moore has accused the county of mismanaging bond funds set aside for the racetrack. The Pima County Attorney’s Office has called his concerns largely baseless.

Despite all that, Moore has high praise for Huckelberry, calling him honest and a friend.

Huckelberry has similar praise for his once and possibly future critic, saying that despite once having a bumper sticker poking fun at the lawsuit, he also likes Moore.

What’s striking about Huckelberry, Pima County Supervisor Ramón Valadez says, is his willingness to do what he thinks is best for the public, even if it means encouraging the board to make politically unpopular decisions.

For example, he asked the three Democrats on the board to slim down the county’s Health Department, which once had more than 3,000 employees. Nobody wanted to do it, but the county’s health-maintenance organization had gone from profitable to hemorrhaging cash after losing its contract to treat indigent patients in the Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System.

Jonathan Walker, former president and CEO of the Tucson Convention and Visitors Bureau, cites Huckelberry’s evenhanded approach to problems.

Even when the supervisors threatened to withhold funding to the bureau, Walker says, Huckelberry and his staff were always willing to listen.

“He understood that it was a partnership,” Walker says. “He was about results and left marketing (of Tucson) to the professionals.”

His adversaries might not like his ideas, but they respect where he’s coming from. That will be tough to replicate. Developer Diamond said he now has a new concern: wondering who might fill his shoes when Huckelberry is finally ready to retire.

It’s unlikely that will happen anytime soon. Huckelberry says he isn’t ready to retire — or as his critics might say, give up his throne.

And it’s clear his bosses don’t want him to. His $230,000-a-year contract, which follows the four-year election cycles of the supervisors, isn’t up until 2017.