Drive around unincorporated Pima County, and it’s evident: Roads are falling apart, ranking as the No. 1 complaint people have about county government.

County officials know it.

“We didn’t do the pavement preservation work that needs to be done,” Transportation Director Priscilla Cornelio said.

As a result, about 60 percent of the county’s paved roads are in poor or failed condition, leaving taxpayers to wonder, with a budget of more than $80 million, what they are getting for their money.

Where the money goes

For next year, the county administrator has recommended a $54.8 million transportation spending plan. Ninety percent of the money comes from taxes collected by the state and redistributed to local governments. The Highway User Revenue Fund is fueled by gas taxes, and the Vehicle License Tax comes from vehicle registration fees.

The largest single expense is a $19 million debt payment to fund projects approved in the 1997 HURF revenue bond. Voters approved a county plan to borrow $350 million against future payments from the state.

That, along with bond projects approved in 2004 and 2006, greatly increased regional roadway capacity.

“I always say that we transformed the northwest side of town,” Cornelio said, noting many of the past bond transportation projects expanded roadways on the growing northwest side.

But while borrowed money was paying for needed new and expanded streets, the county still lacked funding to maintain existing roadways.

“We stopped doing maintenance because the key issue was capacity,” Cornelio said. “We need to start thinking about how we can keep up with the investments we’ve made.”

Like most governmental operations, transportation spends a significant portion of its budget on employee-related costs.

Salaries and benefits for the department will likely total more than $16.4 million next year.

About $2.5 million is slated for repair and maintenance supplies and $3.4 million for landscaping services.

Another $3.7 million is spent for motor pool services, and $6.3 million pays for transit obligations to the Regional Transportation Authority.

The share of the transportation budget going to personnel expenses versus actual road work, whether it’s repairs, pavement preservation or new construction, has been a subject of concern for some.

The issue reached the Arizona Legislature earlier this year in the form of a bill — albeit one that failed — that would have mandated county governments spend no more than 20 percent of their HURF and VLT funds on “administrative costs.”

Pima County’s transportation department will spend about 30 percent of its state funds on employee expenses this year.

“It’s always been that way,” Pima County Administrator Chuck Huckelberry said. “No city, town or county funds its transportation department through the general fund.”

Other county departments spend much larger proportions of their overall budgets on personnel expenses, he said.

As much as 80 percent of the sheriff’s department budget funds employee costs, and more than 90 percent of superior court spending goes toward personnel expenses.

Also by comparison, the Maricopa County Department of Transportation will spend about 26 percent of its state support on employee costs.

Long-standing inequity

For more than 40 years, state pass-through taxes have been the main, and sometimes only, source for local transportation funding — as well as a source for discord.

Vehicle licensing taxes are distributed to counties based on each one’s unincorporated population.

That formula has kept the funding evenly disbursed on a per-capita basis.

The HURF gas tax, however, is doled out using a different formula.

Those funds are distributed based on countywide fuel consumption and on a portion of unincorporated population.

That system has been the source of what Pima County officials see as an unequal distribution model.

“It’s been a long-standing inequity,” Huckelberry said.

Gas tax money is sent to counties based on the total fuel sales within the county, whether the sales occurred in incorporated or unincorporated areas, so Maricopa County gets credit for sales in the 24 incorporated municipalities where most of its residents live.

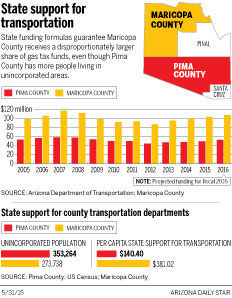

The state’s most populous county has slightly more than 273,000 people living in unincorporated areas, and receives $380 per capita in transportation funding.

Meanwhile, Pima County, with the largest unincorporated population in the state — more than 353,000 people — gets $140 per capita.

In total, Pima County will receive about $49.6 million in state transportation funding by the end of this fiscal year, while Maricopa will get $104.3 million, despite having fewer unincorporated area residents.

Huckelberry said the disproportionate funding model has allowed Maricopa County to maintain roads to a much greater degree than Pima County.

“They even have a pavement overlay program they pay for out of HURF, and we haven’t been able to afford that in years,” he said.

With more money at its disposal, nearly 90 percent of Maricopa’s 2,087 miles of paved roadways are in good or excellent condition, according to Maricopa County transportation documents.

Meanwhile, 60 percent or more of Pima’s 1,854 miles of paved roads have fallen into disrepair.

“They’ve made sure to take care of their own backyard, while in Pima County we’re on our own,” Pima County Supervisor Richard Elías said of the state Legislature, which sets the HURF distribution formula.

New revenue sources

That the state gas tax has not been changed since 1990 is also becoming a sore spot.

The 18-cent-per-gallon tax makes up the largest portion of transportation funding. But even as the state’s population has grown, the amount of money the tax brings in has declined over the years.

ADOT figures show the tax brought in nearly $708 million in fiscal 2007, but receipts have fallen since then. In fiscal 2014, for example, the fuel tax brought in $633 million.

“It’s mostly because people are driving less and getting more fuel-efficient cars,” Cornelio said.

County officials anticipate receiving $53 million in state support next year, which would bring Pima up to 2009 levels after years of dwindling support.

Government leaders across the state have asked the Legislature to increase the gas tax to bring in more funding for transportation.

“That would be the most efficient and fair way to tax people for road improvement,” Elías said, since the tax on fuel amounts to a user fee for people who drive the roadways.

But he’s not optimistic the Legislature will look seriously at an increased tax anytime soon.

“What you have is a bunch of elected officials who are completely intransigent on the issue,” he said.

Huckelberry has suggested supervisors augment transportation funding with local sources, particularly a countywide sales tax.

Supervisors could enact a two-cent sales tax by unanimous vote, all or a portion of which could be dedicated to transportation.

“That’s extremely unlikely,” Elías said.

That’s because some supervisors would be opposed to new taxes, while others might see a general sales tax as regressive, taking a larger portion of take-home pay from the poor than from the middle class or wealthy.

In the absence of a permanent new funding source, the county likely will have to continue borrowing to not only fund new roads but to maintain existing ones. That’s a question that will be resolved in the planned November bond election, where one of the seven questions before voters is whether the county should borrow $160 million to fund road repairs throughout the region.

“We’re either going to accept the fact that we have Third World streets and highways or come to grips with the fact that we have not adequately funded the obligations,” Huckelberry said about transportation funding.

Supervisors plan to adopt a final budget June 16.