More than 71,000 Tucson Water customers in unincorporated Pima County will see their water bills rise in December after the Tucson City Council voted to increase water rates for a subset of customers.

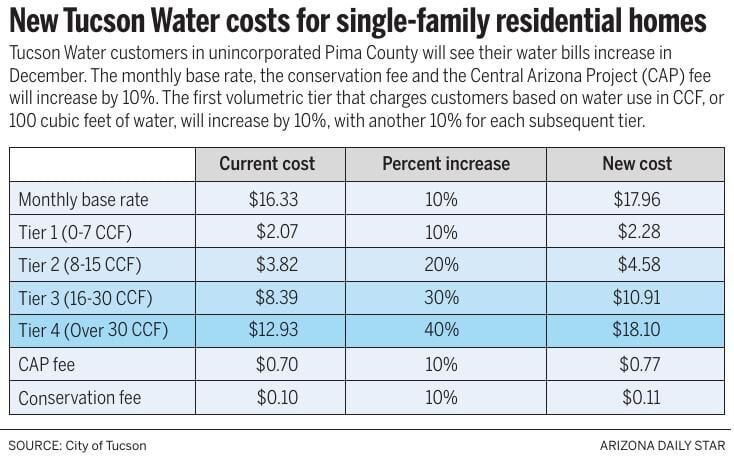

Council members voted in June to raise water rates by 10% with a higher-tiered cost based on water usage for customers in unincorporated areas. Those rate increases will not affect Tucson Water customers in jurisdictions such as Oro Valley, Marana and South Tucson, but rather unincorporated county areas including the Catalina Foothills and Avra Valley.

We are sharing Arizona Daily Star reporters' and photographers' favorite work from 2021.

The decision was solidified by a City Council vote in October and has created a significant rift between city and county officials. While the city says it costs more to deliver water to unincorporated areas, county officials have questioned the true cost and called the move “discriminatory.”

City Council directed staff to conduct a study to determine the difference in costs between providing water to inside city customers and unincorporated areas. The study found unincorporated water service costs 5% more, but some have taken issue with the study’s methods and the efficacy of the findings.

At its Nov. 16 meeting, the Pima County Board of Supervisors will consider legal options to challenge the rate increases for nearly 29% of Tucson Water’s customers.

The average Tucson Water customer in unincorporated county limits will see monthly water bills increase from $50.28 to $56.45 per month, according to the city.

Cost of service

In April, the county's Board of Supervisors voted 3-2 to oppose differential water rates the same day the City Council issued its notice of intent to implement them.

Now, with increased rates set to take effect Dec. 1, the city anticipates earning about $10 million in extra annual revenue to use for infrastructure maintenance, climate resiliency and providing low-income assistance programs.

The city has maintained that raising water rates is purely a policy decision and is justifiable on those grounds alone, but City Council directed staff to conduct a cost-of-service study anyway.

That decision came after Chris Avery, principal assistant city attorney, looked into the legality of imposing differential rates based on an existing state statute and Tucson city code. Both suggest increasing water rates should be based on the cost of providing water.

Avery also pointed to an Arizona Supreme Court ruling that says municipally owned water utilities can charge more for water service outside “corporate limits.” Ultimately, he recommended any differential rate adopted undergo a cost-of-service study before final adoption in order to withstand any legal challenges to the reasonability of the rates.

However, Avery said since revenues generated will stay within the utility, “Tucson Water’s rates, in the aggregate, are ‘cost-of-service’ rates.”

The consulting firm Galardi Rothstein Group and Raftelis conducted the cost-of-service study and found it costs 5% more for the water and infrastructure it takes to deliver water to unincorporated areas than within the city.

“That's primarily a function of the density of development,” said Harold Smith, vice president of Raftelis. “Outside city customers are spread out more than inside city customers, so you just need more pipe to get it to all the different locations.”

The firm also assessed cost of service over a range of returns on investment, or how much more it costs to provide water to outside city customers in order to recoup the same initial investment as inside city customers. Using this approach, which is called the utility method, the company found the differential rate ranges from 9% to 26%, which encompasses the 10% base increase the council adopted.

Pima County Administrator Chuck Huckelberry and members of Tucson’s Citizens’ Water Advisory Committee — a group established in 1977 to advise mayor and council on water resource planning for citizens in and outside city boundaries — have questioned this methodology since Tucson Water doesn’t consider rates of return when setting current water rates.

“Personally, I considered the rate of return was more appropriate for a private water company, that somebody needs to make a profit, have some formal rate of return,” said Mark Taylor, the chair of the advisory committee. “I didn't think it was an appropriate methodology. I think another company could have done a different methodology and come up with a different number.”

But Smith says this is a common way municipalities determine differential rates.

“That's kind of a misconception on the part of a lot of people, that this utility basis is only used by investor-owned utilities or private water companies,” Smith said. “It's very common in the industry, throughout the country, for a municipal utility to calculate both outside city rates and wholesale rates using the utility basis.”

City residents considered “owners”

According to Tim Thomure, interim assistant city manager, the rates of return considered in the study represent a risk the city bears that unincorporated residents do not.

“There's risk that is taken by the city and that risk is only borne by the owners, which are the city residents,” he said. “Noncity residents do not contribute directly to the insurance policies or the ultimate backup of the operation of the utility to the same degree that city residents or owners do. It's an ownership, nonownership discussion.”

Huckelberry has taken issue with the notion only city residents own Tucson Water, as all ratepayers support the utility.

“The entire utility debt and risk is held by ratepayers and not residents of the municipality,” Huckelberry wrote in a letter to the advisory committee on Sept. 8. “In the event of a force majeure, the city of Tucson would secure mitigating debt against future revenues generated by ratepayers, thereby leaving Tucson Water residents in the unincorporated areas as exposed as Tucson resident ratepayers.”

A force majeure occurs when unforeseeable, unavoidable circumstances prevent someone from fulfilling a contract.

But Thomure said “any default on the finances of Tucson Water, if it should happen, that falls on the city, that doesn't fall on all customers.”

And according to Smith, “it is common practice within the water industry to consider customers located outside the corporate limits of the owning municipality to be non-owners.”

Huckelberry also points to the city’s intergovernmental agreements with the Pascua Yaqui Tribe, the Tohono O'odham Nation and Tucson Unified School District that exclude the entities from higher water rates, even though they own land in unincorporated areas.

“We charge the differential water rates based on policy, but not if it's in violation of a contract or an (intergovernmental agreement),” Thomure said.

Study concerns

District 1 Supervisor Rex Scott, who represents many constituents residing in unincorporated areas, shares Huckelberry’s concerns about the cost of service study.

“The cost of service study that was done by the city, I think is inadequate, and doesn't look at cost of service throughout the Tucson water service area,” he said. “It cherry-picks information to justify something that the city has been intending to do all along.”

The city adopted a 10% base rate increase before conducting a study to determine if that figure adequately reflects how much more it costs to serve unincorporated residents.

“I think the only reason that they did the cost of service study was because they were advised after the fact to do so by the city attorney's office,” Scott said.

City Councilman Paul Cunningham, a staunch proponent of differential rates, says if anything, the cost of service study didn’t do enough to illustrate the strain on city water customers for paying the same rates as unincorporated residents.

The city says increasing water rates could encourage annexation and ultimately increase Tucson’s portion of state shared revenues. Thomure estimates Tucson is losing out on up to $50 million a year for the population it serves outside of the incorporated county.

“There's no way we can produce a study that will satisfy (the county), no matter what happens,” Cunningham said. “I think our study didn't cover enough data that shows how the city residents are taking a higher burden.”

The advisory committee reviewed the cost of service study in October but didn’t take a vote on a recommendation to City Council before it officially set the rates Oct. 19. However, many committee members expressed concern about the study.

“Is there really a difference in cost of service between the two regions? I'm not sure this report really showed the true case whether there is or not," Taylor said.

But as the county considers suing the city over differential water rates, Taylor’s biggest concern is a growing rift between two regional partners.

“This has definitely divided us even further. It's divided the City Council with the Board of Supervisors, and it even divided the ratepayers within the Tucson Water system into two classes,” he said. “To me, this is not the time to divide Southern Arizona. I think that was one of our big concerns, and I'm afraid that's definitely showing.”

Thomure said he can’t comment on the county’s “intent to pursue legal action,” but said the differential rates’ implementation was “done in compliance with state law.”

“(The cost of service study) does demonstrate, first and foremost, that there is a differential cost,” he said. “And secondly, depending on the amount of rate of return that one would assume, it also demonstrates that what mayor and council already decided is very fair and reasonable.”