Pictures of children behind what appear to be cages, reports of 1,500 children lost, stories of parents being separated from their children to be criminally prosecuted, and photos of long lines of families waiting outside ports of entry have filled the news recently. But what is really happening?

The Trump administration is reacting to rising month-to-month numbers of mostly Central American families and unaccompanied minors coming to the United States. The administration says they are trying to take advantage of the country’s asylum laws.

To deter people from coming in the first place, Attorney General Jeff Sessions recently announced a “zero tolerance” policy in which Border Patrol agents are instructed to refer for prosecution everyone they apprehend, including parents traveling with their children.

The administration is separating children under two situations: one, if the parent can’t prove it’s their child; and two, if the parent is criminally prosecuted, said Ronald Vitiello, acting deputy commissioner of Customs and Border Protection, in a recent congressional hearing held by U.S. Rep. Martha McSally, R-Tucson.

While CBP hasn’t provided numbers of parents prosecuted and separated in Arizona since the policy went into effect, a Department of Homeland Security spokesman said Friday that the Border Patrol along the entire U.S.-Mexico border held 1,995 minors traveling with 1,940 adults between April 19 and May 31 while the adults were prosecuted.

Why is the administration taking such measures?

To the Trump administration the border is out of control and in crisis.

This year’s apprehension numbers are considerably higher than last year’s, but 2017 was an unusual year. As the Migration Policy Institute recently reported, after the November 2016 elections and in the early months of the Trump administration, would-be migrants held back to see how immigration enforcement policies would play out.

Overall, Border Patrol agents have made 252,187 apprehensions so far this fiscal year (from October through May) along the Southwest border. In 2017, agents made about 300,000 arrests total, the lowest number since 1971, and as the Migration Policy Institute puts it, a far cry from the peak of 1.6 million in fiscal year 2000.

The recent rise in apprehensions, the D.C.-based think-tank reported, indicates they may return to the 330,000 to 480,000 levels seen in fiscal years 2010 through 2016.

What has changed, though, is the makeup of those coming across. Increasingly, these are families and unaccompanied minors. In fiscal year 2013, 13 percent of those apprehended by Border Patrol along the Southwest border were families or minors traveling alone, compared to nearly 39 percent in 2017. So far this year, about 36 percent of those arrested are families or unaccompanied minors.

The rise in the number of families has been particularly stark in the Border Patrol’s Yuma Sector, where it has risen to nearly 8,800 as of May, up from 187 during the same period in 2013.

Is this the first time the number of families and unaccompanied minors has spiked?

No. The number of unaccompanied minors, for instance, has been rising for several years now, occasionally ebbing and flowing.

What’s different is the more constant growth in the number of parents traveling with their children, particularly since 2014. That year, the Border Patrol made nearly 140,000 apprehensions along the Southwest border of unaccompanied minors and parents traveling with at least one child.

In this 2014 photo, taken during the Obama administration, detainees slept or watched TV in a holding cell where hundreds of mostly Central American immigrant children were processed by U.S. Customs and Border Protection in Nogales. A major difference then is that many children were traveling by themselves when they crossed the border.

In response to that increase, the Obama administration started to house unaccompanied children in an old warehouse in the Nogales Station, where some photos that recently resurfaced were taken. The Nogales Placement Center, as it was called, at one point held about 900 children, separated by gender and age groups in sections divided by 10-foot-tall chain-link fences with razor wire on the top, which officials said was there before the youths arrived. The warehouse had been used in the early 2000s to process Mexican nationals.

The Obama administration also expanded family detention temporarily by outfitting part of the Federal Law Enforcement Center in Artesia, New Mexico, and opening a new facility in Karnes, Texas.

Is the process different for those who present themselves at a port and those who flag a Border Patrol agent between ports?

Because asking for asylum at a port of entry is not illegal, those who do so can’t be criminally charged.

While there are reports of some families being separated at the ports, many of those who have recently arrived at the Nogales DeConcini Port of Entry have been released with an ankle-monitoring bracelet and a notice to appear before an immigration official at a later date. The Trump administration has criticized this as “catch and release.”

Two shelters in Tucson take in families that have recently arrived at the Nogales DeConcini Port of Entry. Above, drawings by children and adults who have stayed at Casa Alitas.

There are two shelters in Tucson that take in these families so they can eat, shower and rest while relatives or friends make travel arrangements, usually a day or two later.

The recent issue at the port in Nogales has been the slow pace in which officials are processing the families. The delay has led to long lines and parents with children having to wait multiple days, sleeping on the floor and relying on volunteers for food and water.

But if immigrants come in between the ports of entry, even if they ask for asylum, the Border Patrol is first referring them for prosecution for illegally entering the country.

At this point, because the children cannot legally be held in criminal detention, they end up being separated from their parents and turned over to the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Refugee Resettlement.

The agency contracts with private shelters. There are a handful of them in Arizona operated by Southwest Key, which describes itself as the largest provider of shelter services for unaccompanied minors in the country. Here, a caseworker tries to find a sponsor for the child, usually a relative or close friend in the United States.

The parent, on the other hand, goes before a federal judge. If it’s their first time crossing, they usually get sentenced to time served and are transferred to ICE custody where they can be deported or claim a fear of returning to their home country and seek asylum.

It is at this point where it becomes unclear what exactly is happening with the minors and parents. Questions remain about the length of time parents remain in ICE custody before they are deported and what happens with the minors.

When parents being prosecuted started to ask about their children in recent weeks, Tucson magistrate judges put on the record the fact that they had been separated. Then the judges started to recommend that families be reunited and most recently instructed the federal prosecutor to ask about the children’s locations and provide that information to the parents.

How are the parents and children identified to facilitate reunification?

Initially, criminal defense attorneys reported seeing parents apprehended in the Tucson Border Patrol sector with a yellow bracelet as an identifier. CBP later explained the agency uses different colors of paper bracelets based on the location to identify a parent and child traveling together and unaccompanied minors while in custody.

Acting Deputy CBP Commissioner Vitiello said during a recent congressional hearing that Border Patrol agents get biographical information of everyone who is taken into custody as part of the booking procedure. “That’s how we try to establish whether they are related or not. … That all becomes part of their record as they come in.”

Did the government lose 1,500 children?

In April, a Health and Human Services official reported not knowing where 1,500 children who came to the United States without parents or guardians were. Around the same time the Trump administration announced its “zero tolerance” policy of prosecuting everyone, regardless of whether the adults were traveling with children or not. This led to the confusion that the government had lost more than 1,000 kids who had been separated from their parents.

But the children the federal agency was unable to locate after a 30-day follow-up call were unaccompanied minors traveling alone. And while some of them could be indeed lost, another possibility is that their sponsors —usually relatives or close family friends — didn’t want to respond when officials called, especially during this political climate.

During a recent visit to Southern Arizona, DHS Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen said the children were not lost. “These are not children who were separated,” she said. “Unfortunately, under the system many are placed with families who themselves are illegal aliens,” and they are not returning calls. “They are not lost; they just don’t want to be found,” Nielsen said.

How easy is it to reunite parents and minors after the parent is prosecuted?

The U.S. Attorney’s Office has said through a spokesman that it is working with federal law enforcement agencies and the Office of Refugee Resettlement to develop a mechanism to help defendants find out the location of their children. It could be a point of contact in detention centers or a phone number parents can call, among other options.

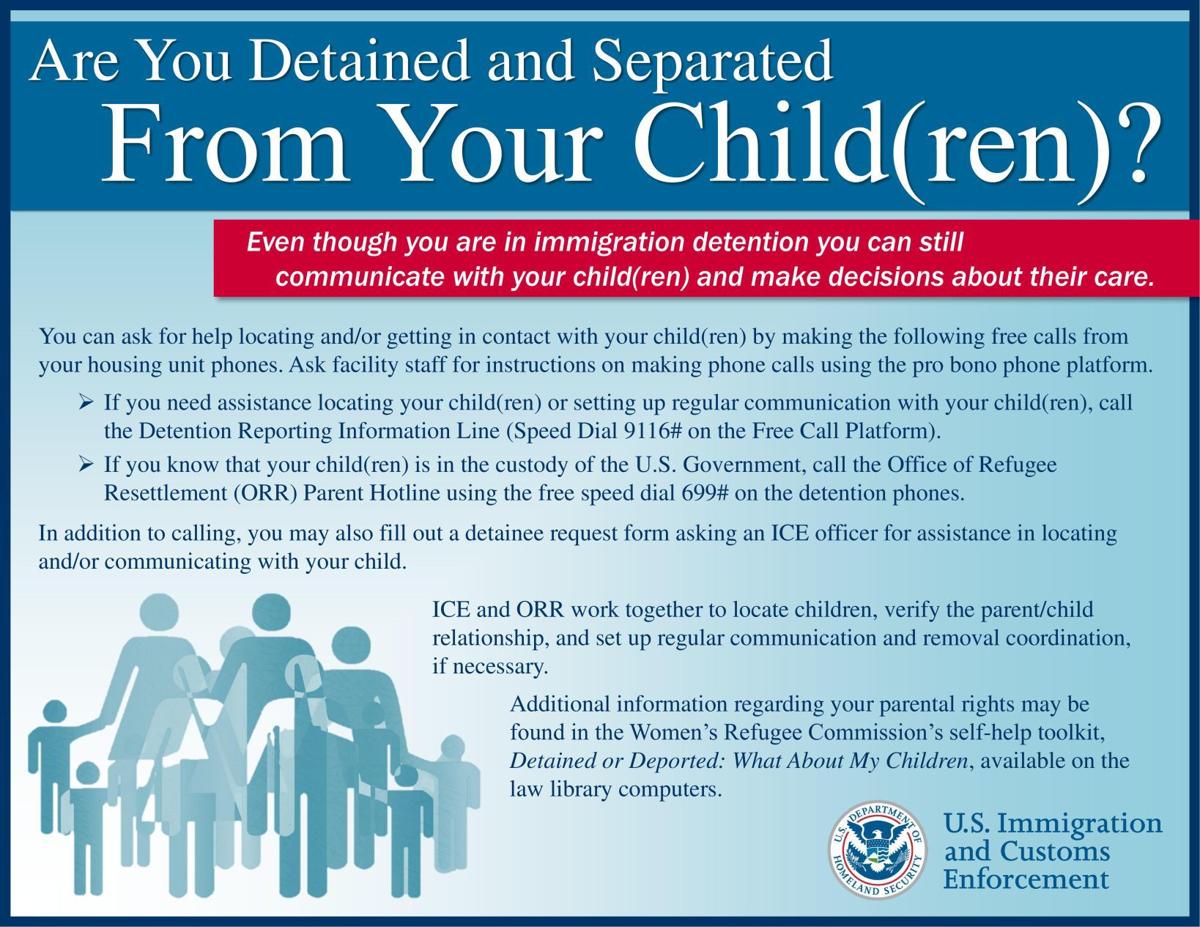

ICE officials said they will post new information in all facilities where people are held over 72 hours, advising detained parents who are trying to locate and/or communicate with a child in the custody of Office of Refugee Resettlement to call the Detention Reporting and Information Line for assistance.

Separated parents who are still in U.S. Marshals Service custody and have not yet been transferred to ICE can also call that line. The information provided by these parents will be forwarded to the Office of Refugee Resettlement, a spokeswoman said. “ICE and ORR will work together to locate separated children, verify the parent/child relationship, and set up regular communication and removal coordination, if necessary.”

An ORR spokeswoman said parents attempting to determine if their child is in the custody of the Office of Refugee Resettlement should contact the ORR National Call Center (www.acf.hhs.gov/orr/resource/orr-national-call-center) at 1-800-203-7001.

Outside entities, attorneys, or other individuals seeking unaccompanied minor case file information must make a request to ORR (www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/orr/resource/requests-for-uac-case-file-information) under the appropriate policies and procedures.

From previous experience, parents are generally very confused about how to contact their child, said Laura St. John, who is with the Arizona-based Florence Immigrant and Refugee Rights Project.

And if the child is too young to communicate, “it can cause additional complications in trying to put parent and child back in contact,” she said.

Can families still seek asylum even after they are prosecuted?

Yes, officials have said that the two processes, criminal prosecution for illegal entry and claiming credible fear, are not incompatible.

L. Francis Cissna, director of U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, responded that his understanding of the U.S. commitment under the refugee convention was that the U.S. was not going to return people to a country where they may suffer persecution and that the administration was not doing that.

“They may in the end get asylum, but that doesn’t mean that they didn’t violate the law … and the law is the law. They should be prosecuted and punished for that. But that doesn’t mean they can’t also get asylum,” he said.

Why are families treated differently?

If a parent is going through criminal prosecution, the child cannot be held in criminal detention facilities. But even when families are kept together, children cannot be detained with single adults and family detention space is limited. Currently, there are 2,700 beds available nationwide.

The president’s 2019 fiscal-year budget for DHS includes funding for 52,000 detention beds, including 2,500 beds reserved for family units. For those who are not considered a threat but who may pose a flight risk, the request includes funding to place up to 82,000 people, on average daily, in the alternative-to-detention program, which includes home visits and electronic monitoring.

There are also legal protections for child migrants. The 1997 Flores v. Reno court settlement, for example, as the Migration Policy Institute recently wrote, requires the government to release children from immigration detention without unnecessary delay to, in order of preference, “parents, other adult relatives, or licensed programs willing to accept custody.”