Alma Jacinto covered her eyes with her hands as tears streamed down her cheeks.

The 36-year-old from Guatemala was led out of the federal courtroom without an answer to the question that brought her to tears: When would she see her boys again?

Jacinto wore a yellow bracelet on her left wrist, which defense lawyers said identifies parents who are arrested with their children and prosecuted in Operation Streamline, a fast-track program for illegal border crossers.

Moments earlier, her public defender asked the magistrate judge when Jacinto would be reunited with her sons, ages 8 and 11. There was no clear answer for Jacinto, who was sentenced to time served on an illegal-entry charge after crossing the border with her sons near Lukeville on May 14.

Parents who cross the border illegally with their children may face criminal charges as federal prosecutors in Tucson follow through on a recent directive from Attorney General Jeff Sessions to prosecute all valid cases, said U.S. Attorney’s Office spokesman Cosme Lopez.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection started referring families caught crossing illegally for prosecution several weeks ago, Lopez said. Those prosecutions unfold both in Streamline cases and through individual prosecutions.

On Thursday, Efrain Chun Carlos, also from Guatemala, received more information than Jacinto when he asked Magistrate Judge Lynnette C. Kimmins about his child during Streamline proceedings.

“I only wanted to ask about the whereabouts of my child in this country,” Chun said.

Kimmins responded she didn’t know where his child was and suggested he ask officials at the facility where he will be detained.

Christopher Lewis, the federal prosecutor at the hearing, told Kimmins that children from countries that are not contiguous to the United States will be placed in foster care with the Office of Refugee Resettlement.

“When they will be reunited, I cannot say because that’s an immigration matter,” Lewis said.

A spokesman for CBP did not provide information about the process for parents and children apprehended by Border Patrol and those presenting themselves at ports of entry.

It is still unclear what happens to the children of parents who are prosecuted, said Laura St. John, legal director with the Florence Immigrant and Refugee Rights Project based in Arizona. Technically, once the child is separated from the parent they are deemed an unaccompanied minor and their cases should be processed separately.

If parents are deported, they can ask that their children go with them or ask that the child be reunited with another sponsor in the U.S., which gives the child a chance to fight an immigration case on his/her own as an unaccompanied child, consulate officials and attorneys said. If the parent decides to fight the case and is released from ICE custody, they can request to be reunited outside detention.

deterrent effect

Lopez said he did not know how many prosecutions of parents with children had occurred so far. The Arizona Daily Star found nine Streamline cases last week in which defendants asked the judge about their minor children.

The parents in those cases were arrested by Border Patrol agents near Lukeville between May 12 and May 15. Eight of them were from Guatemala and one was from El Salvador. Seven were men and two were women.

In an April 6 memorandum to federal prosecutors, Sessions announced a “zero tolerance” policy for first-time illegal border crossers. On May 7, he said the Department of Homeland Security was referring 100 percent of illegal crossers for criminal prosecution in federal court.

“If you cross this border unlawfully, then we will prosecute you,” Sessions said. “It’s that simple.”

He included parents who come with their children in his directive.

“If you are smuggling a child, then we will prosecute you and that child may be separated from you as required by law,” he said.

Criminal prosecutions of parents illegally crossing with their children have unfolded in Texas for several months, as have separations of families through civil immigration measures along much of the U.S.-Mexico border, according to media reports.

Border Patrol statistics show fewer apprehensions of families in sectors in Texas so far in fiscal 2018, which began last October, compared with the same period in fiscal 2017. Meanwhile, those apprehensions rose 103 percent in the Yuma Sector and 69 percent in the Tucson Sector.

In an interview with National Public Radio, White House Chief of Staff John Kellly said family separation could be a tough deterrent, “a much faster turnaround on asylum seekers.”

The children would be “put into foster care or whatever,” Kelly said in response to criticism that taking a mother from her child is cruel and heartless.

“But the big point is they elected to come illegally into the United States and this is a technique that no one hopes will be used extensively or for very long,” Kelly told NPR.

Border Patrol agents in the Tucson Sector apprehended 2,500 people crossing the border as families from October to the end of April, CBP records show. In the Yuma Sector, agents apprehended nearly 8,000. The borderwide total is nearly 50,000, down from 59,500 during the same period in fiscal 2017.

At Arizona’s ports of entry, about 5,500 people traveling as families were deemed inadmissible from October to April. The borderwide total was 30,000, up from about 21,000 during the same period in fiscal 2017.

Casa Alitas helps some

The number of Salvadorans arriving at the border has increased about 40 percent compared to last year, said German Alvarez Oviedo, the consul in Tucson. He estimated the total is still in the dozens but didn’t have final numbers yet.

“There’s no policy of family separation as such,” he said, “but by declaring a zero-tolerance policy and prosecuting everyone who comes in, it results in family separation.”

If the parent gets sentenced to time served, which is common for first-time entrants, officials should consider keeping young children with their parents, he said.

“It’s not the same to be under the care of the mother than a shelter, especially when the child is 2,” Alvarez Oviedo said.

The government has struggled to handle the increase of families coming across the border — at ports of entry and between the ports — since the numbers first started to rise in 2014.

Initially, officials allowed parents with children to enter the country under humanitarian parole. They were dropped off at a bus station in Tucson with an appointment to meet with ICE at their final destination within two weeks.

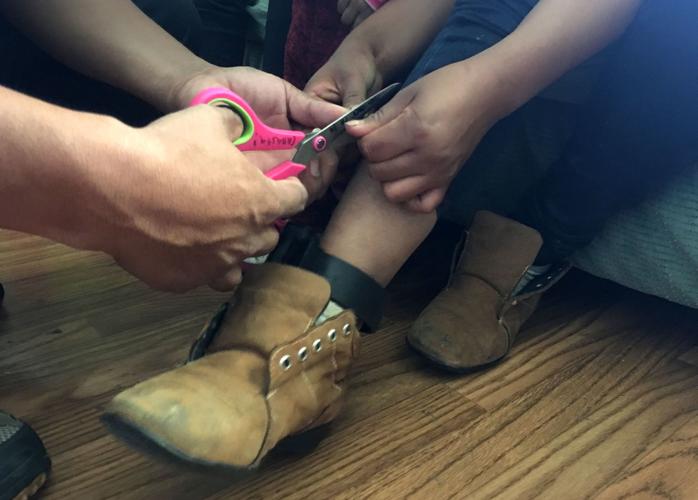

Later, officials started to release them, but with an ankle bracelet to limit what critics called a catch-and-release policy, since not all parents kept their appointments. The government also increased detention space for families.

This past week, more than 100 parents and children — many of them Guatemalans — lined up at the port of entry in downtown Nogales to be processed for entry into the United States, some waiting more than a day.

In general, the parents waiting to cross at the port who have no prior immigration history are processed and released with their children in Tucson with an ankle monitor and an appointment to meet with immigration officials. In at least one case, the families said, a man with prior immigration violations was separated from his son to be prosecuted.

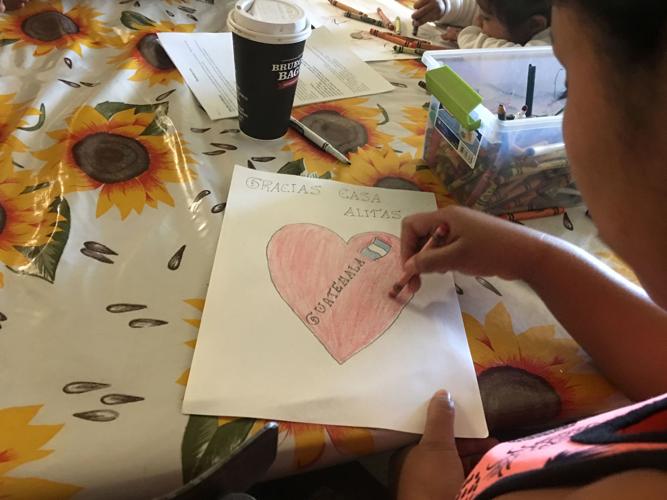

Some of the families the Star spoke with Monday on the Mexican side of the port of entry went to Casa Alitas, a house in Tucson opened by Catholic Community Services to avoid having families spend the night at bus stations. Families can bathe, get clean clothes and eat a warm meal while their relatives buy their bus or plane tickets.

In a written statement, ICE officials said the agency prioritizes placing families in residential centers. But if they are operating at capacity, “We can also look for temporary hotel space or consider alternatives to detention, such as supervised paroles or use of ankle placement for monitoring.”

The families said customs officials at the Nogales port of entry didn’t ask them many questions, besides their reasons for coming to the United States.

Extortion, domestic violence and extreme poverty were all reasons they were seeking a better future in the United States, they told the Star.

The lack of rain also was hurting their ability to survive. For coffee farmers, their fields weren’t producing enough and their crops were more susceptible to plagues they had no money to treat.

Katherine Smith, site and volunteer coordinator at Casa Alitas, said few families came last fall. Then it started to pick up around Christmas, with ICE trying to find placement for 100 people in one day.

It had slowed again until recently, when ICE started to ask Casa Alitas daily if it could take 40 to 60 parents and children the agency was releasing, Smith said.

Smith doesn’t know the reason for the increase, other than the normal rise in Southern Arizona right before the triple-digit heat of summer.

As of May 7, the Florence Immigrant and Refugee Rights Project had served 135 families separated by immigration authorities this year. At this rate, the group said, family separations are on pace to increase 75 percent from recent years.

Given recent announcements by federal officials, they believe the numbers will continue to rise, although it doesn’t mean that all of them were prosecuted, the group said.

“A number of these families appear to have a real fear of returning to their country of origin,” said St. John, the Florence Project’s legal director. “Fleeing or leaving a child behind to avoid being separated by the U.S. government is not a choice any parent should have to make.”

Editors' Note: This story was originally published on May 25, 2018.